Creating a Myth: Conversation with IngridMwangiRobertHutter

How did you start working together as a group with Robert, IngridMwangiRobertHutter?

I purposely try not to speak too much about it, because we are creating a sort of a myth or a fictional personality, trying to redefine the history of this personality. It is very difficult to do, because people always try to split us up into two people. But basically we’ve been together over a decade. And there were different phases. We began by working for each other on projects and then quickly started working together. We had a phase when there was Ingrid Mwangi and Robert Hutter and at some point the two positions became really fused. We incorporated all previous work into the collective. And at that point we named it a collective, but now I’d like to correct you, we’re really not a group or a collective, but we try to be one artistic personality, or what I’d like to call an artist-collective-being.

So it’s not just an artistic concept, but also a life concept?

Yes. In daily life we’re married and we have two children. We also live with this tension of coming from two different cultural backgrounds. Being both artists, we use this personal history and also the artistic endeavour, which was always very similar, because we both studied performance and video art. It started with the medium of the camera turned towards the self and using that as material. So now the self has become a little bit more complex, has become the self made of these two bodies, two minds, two consciousness, two creative trajectories, which now meet in this point in time.

So it was really an organic development between theoreticising about the artistic concept and living it. It goes hand in hand. It is a conceptual idea, of course. It’s art, it’s not reality. Everybody who sees us finds it really difficult to say that we’re one person. But still, now I say I’m one person: I’m IngridMwangiRobertHutter. And I try to develop a consciousness in which I have those two bodies. So when I make art, I put that masculine white body in relationship to this feminine “black” body. This is very exciting, because we are dealing with the materiality of the body. It expands the breadth of the whole theme: the concept for me comes from living. It’s how you live it, how you work with it, how it manifests itself, rather than just projecting the idea that we want to be one person.

Tell us about the issue of violence in your past work and how your approach changed with the creation of the artistic personality you now are?

When I started talking about becoming a collective, there was a whole variety of reactions. Some people just did not accept it, because they were very attached to Ingrid Mwangi’s previous work, which was a lot about racism, the black body and black feminism. I remember one art collector couple: the woman found it such a shame that I’m now sharing my achievements with a man when I could have stood out with this work. It reminded me that of course there are some things that you have to let go of when becoming this collective being. A major part is letting go of your ego and constantly being able to incorporate the ideas and the realities of the other person, like daily exercise.

I really think that this is a model for the future. It’s about rethinking what the ego is and what the nature of self-interest versus common interest is and how we can create common interest as a basis of life. So it’s a kind of microscopic experiment, one which is totally necessary. I find the previous work, while it was very important, was in a way reactionary. I’m being discriminated against and I react, which is correct, but at some point you have to stop reacting and you have to act. You have to take your own position and we do this with art in a public arena. I think the more firmly you do that – put your lifestyle, your ideas and convictions in the social space – then these ideas can filter into the make-up of society. So since we are interested in overcoming cultural barriers and really communicating, we create and demonstrate a common vision. That’s our proposition.

Do you think one of you has a stronger influence on your work than the other?

There is a shift back and forth depending on who is doing what at the moment in question. We have to share all of our life responsibilities. That means making the art, traveling for art, bringing up the children, managing correspondence, dealing with the technology and so on. We have different talents, so part of being a collective being is that we don’t have to do everything the same. Not all parts of an organism have to function in the same way. There are certain aspects, which are carried out by one part and certain aspects more by the other. That’s why you see me traveling more and being more present as a kind of a front figure, which also gets confusing for people, because they find it hard to see more subtle aspects of what’s going on. But really, it’s very balanced.

What about the work that you’re showing here? Can you tell us why you use sugar cubes as a material?

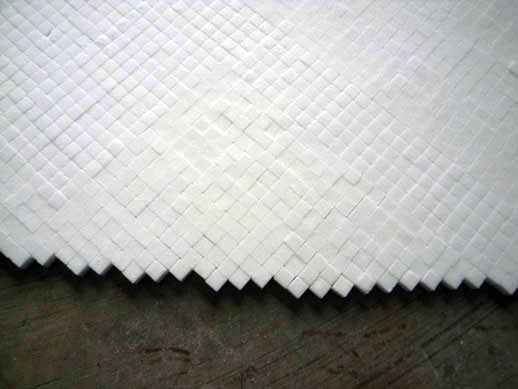

Definitely when you’re working with video it’s interesting to think about the projection surface and not always just depart from the white rectangle on the wall, but to use this ephemeral, light material to meet with other material. In many works you see experimentation with projections on materials, on fabric and so on. In this installation Performance of Doubt, the use of sugar is specifically to create a kind of ambivalence in the work, because it’s dealing with the fragility of life and different life stages. You see the projection of a baby, of a mature woman, of a couple, and an old woman. Most of the images have something to do with fragility or suffering. So at some point it became really important to find some material that typically has a positive connotation. Sugar makes me think of sweetness, it reminds me little bit of snow from its surface and this also has associations with purity. And out of this kind of pure circle – the circle also being a symbol of something complete and perfect – the two-sided wall in the center is jutting out. The wall is like a threshold to the reverse side that shows old age and death. We don’t really know what comes after death. The phase of birth and reaching maturity is on the other side of the wall – the process of trying to live life. So I think the sugar was really necessary to bring this kind of ambivalence into the work.

The baby on one side of the wall seems to be in a kind of safe white environment…

I wouldn’t say safe, but rather sterile, maybe a little bit cold. It’s kind of uncomfortable to see the baby left there. And it was in fact a pretty tough thing to do. Both parts – Ingrid and Robert – were just standing there very concerned during the recording.

So it’s your own baby?

Yes, the video was shot four years ago. At that time I looked at our four month old child and thought about how to hold this helplessness, this absolute dependency that I saw there. I kept this video material, trying to think of a way for the work to make itself evident and in what context I could use it. So it took time before I could use it.

What about the themes in your older works?

To come to the theme of this work, it arose from realizing the limitations of working on such specific topics as racism, discrimination, political issues, war and so on. With time, I see that there are some points that are missing when we talk about these things. We are actually informed about a lot of issues; most of us know that war is bad, but there is also something about human existence, something very fundamental that causes us to repeat our mistakes. I remain interested in very specific issues of violence, but dealing with these on a direct level seems at some point to be missing some fundamental understanding. That’s why coming to this work now is to try to strip things down to the essential, to approach the question of why it’s so hard to be human, so hard to live correctly. One approach was to think about life and death. To look at death is a really difficult thing, I think. Moreover, to look one’s own death. This piece shows my child, myself and my mother, so it’s really a portrayal of how three generations are moving on.

Aneta Glinkowska

Aneta Glinkowska