Gender in Japanese History

“Gender in Japanese History” at the National Museum of Japanese History in Chiba delves into how ideas of gender have influenced people’s lives since the dawn of Japanese civilization. A team of 20 historians spent nearly 12 years researching the topic, which covers prehistory through today. Gender in this exhibition is explored through the three main themes of: 1) Men and women in political spaces, 2) Gender in work and life, and 3) The sex trade and society. While there is not much discussion of the gender binary itself, the show does examine how “men” and “women” as constructed social categories have been assigned certain roles. Particular focus is placed on the lives of cisgender women.

Antiquity

The exhibition begins with the example of Himiko, the “female chieftain of Wa,” who lived until around the year 248. This ruler of ancient Japan proves there is a historical precedent for women wielding political power. It is believed that before the fourth century, thirty to fifty percent of rulers in Japan were women, and that during this time people worked in groups with ambiguous gender roles. Clearer divisions of gender emerged with the establishment of the Ritsuryo legal system imported from China from the sixth century. Artifacts from antiquity on display include haniwa clay sculptures from ancient burial mounds.

The Middle Ages

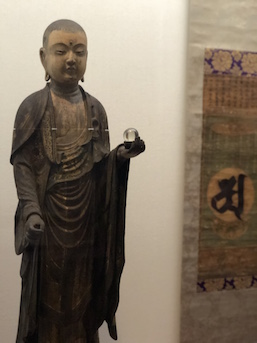

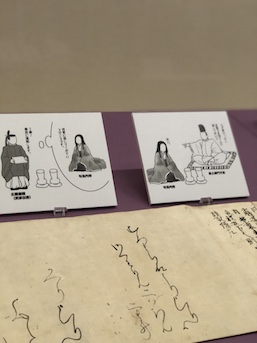

In the Middle Ages, patrilineal ie households were formed across social classes. Still, medieval Japanese women could own and manage property. They also played important roles in Buddhist religious spheres, conducting family rituals and independently pursuing religious activities. In the aristocracy, female attendants called nyobo served ruling men and high-ranking families. Nyobo eventually came to be considered similar in status to their male counterparts for promoting the political and economic status of the family. Nyobo were responsible for conveying royal messages and orders, and their letters were frequently used as official documents.

Early Modern Times

Medieval Japanese women were able to work and own businesses. In early modern times, however, society was restructured based on male-centric rules and ideas, and women for the most part could no longer flourish professionally. Instead, they were largely viewed as “supporters” of men and relegated to certain tasks and roles. During the Westernization movement of the Meiji era (1868–1912), pressure was put on women to be “good wives and wise mothers,” and their actions and appearances were circumscribed accordingly. Still, diversity in gender roles and divisions of labor existed across different regions of Japan and East Asia.

The Sex Trade

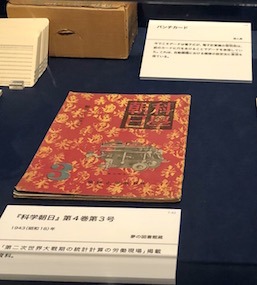

The Modern and Contemporary Periods

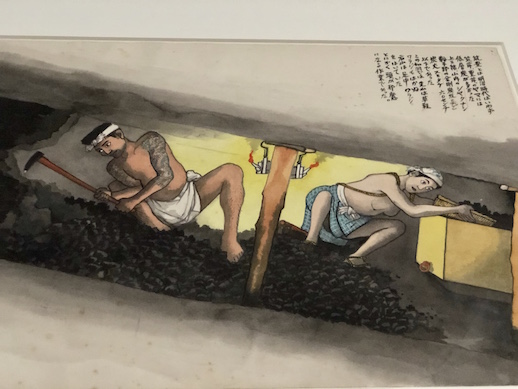

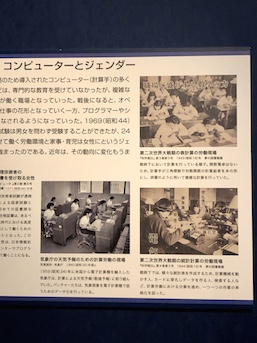

Japan’s industrial age and transformation into an information-based society were supported by men and women alike, with women working in places ranging from coal mines to computer labs and corporate offices. Still, gender roles remained deeply entrenched, with women receiving lower status and pay than men. Women have also long been responsible for most childrearing and duties at home, a situation that continues to this day. The last chapter of the exhibition looks at gender up through the contemporary era.

The World Economic Forum’s 2019 study of gender equality ranked Japan at 121 out of 153 countries, the lowest of the G7 nations. Given constricting gender roles, the exclusion of women from modern political spheres, and the low status and pay of “women’s work” as detailed in “Gender in Japanese History,” we can see how this situation developed. However, as the exhibition also shows, gender roles are a fluid facet of life that has changed throughout history, implying that it is not biology or any immutable law that makes the status of women in Japan what it is.

This exhibition is a fascinating account of how ideas of gender and the roles that result from them exert power over people’s lives. It is recommended for anyone who wants to understand Japan as a society. More dissection of the gender binary and examples of gender fluidity would have enhanced the scholarship. English is provided for the introductions of each section, but is otherwise limited. “Gender in Japanese History” ends December 6th, 2020.