Interview with Terry Winters: The Painting is Completed as Something Beyond My Imagination

Terry Winters Photo: Tokyo Art Beat

American painter Terry Winters has been exploring the relationship between modern abstraction and the structures of the natural world for over 40 years. Many of his early works depict organic forms reminiscent of plants, which eventually evolved into compositions of biological systems, mathematical diagrams, musical notation, and data visualization.

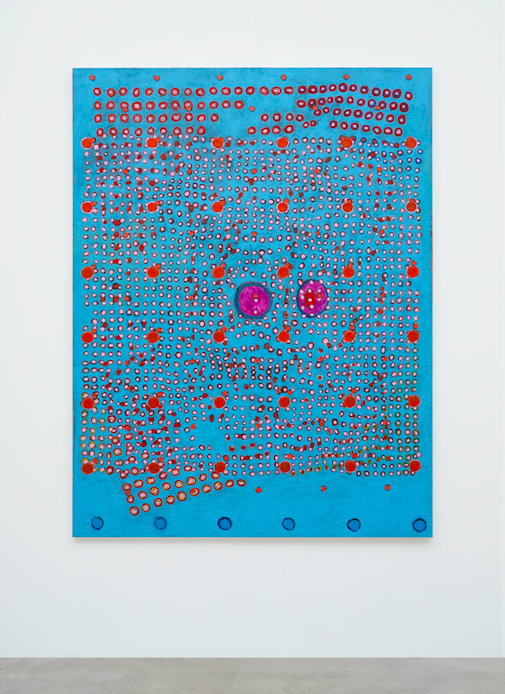

His current solo exhibition Terry Winters: Imagespace at Fergus McCaffrey Tokyo, features six new paintings that could be seen as plant cells observed through a microscope or a mandala that charts a religious view of the cosmos. We will explore what brings his paintings about through a conversation between art critic Ryo Sawayama and Winters, who visited Japan for his solo exhibition.

Painting is a visual system that opens up meaning and psychic dimensions

——What are some of the new challenges, experiments, or thoughts you have developed in the new works?

Winters: These paintings are the continuation of a body of work I have been building over the past few years. And they are all based on a large series of small black-and-white drawings.

The drawings are used to develop a vocabulary of forms. The paintings function for me as a visualization system, a way to access possible meanings or psychic dimensions contained in those prototypical drawings.

——Your paintings seem to have an evident relationship between form and color. For example, Point Array (2022) is composed of dots and colored surfaces, but the dots are painted pink or red, and the colored surfaces underneath are painted blue. In other words, each element is painted in a different color. How do color and form relate to the structure of the painting?

Winters: Color adds an unknown or wilder element to the narrative of the drawings. And I think each color has a physical or chemical role in determining the final forms or image. Each painting is a laminated structure that has been layered over time. The colors shift and move in some way and build to surprising conclusions.

——The lines in your drawings suggest something that unfolds in time. But color also has a temporal process, doesn’t it? Can you tell us more about the process and time in painting in terms of the relationship between drawing and color?

Winters: Color is both a way of marking time and sequencing the construction of the pictures. My drawing process develops within a narrow bandwidth since I only use a range of black-and-white materials. So it is more difficult to differentiate the period over which each drawing develops. Changes occur in the drawing process, but they’re limited and incremental.

In contrast, the paintings offer a wide range of physical possibilities. One is confronted with an enormous array of material options and processes. And color allows for more dramatic shifts of direction. Even in practical terms like drying times. Every pigment has its time frame. So the paint itself is imposing actual demands. And it is by working and playing with those practicalities that the possibility of a new painting emerges. And my relationship with those developing images is in a state of constant change. I’m looking to find an emotionally rich and abstract environment.

Produce an image free from a particular scale

——Your paintings consistently relate to the natural sciences or something else. Can you tell us how you came to this idea?

Winters: I think there are several reasons. One is that I had been looking for a way to get drawing back into my work. The paintings I was doing in school were very minimal, almost monochromatic, and I wanted to find a way to justify traditional drawing within that context of minimalism and process art.

I was also looking for a subject I could take as a given, and nature seemed to be the ultimate found object in the Duchampian sense. I saw natural history illustrations and technical diagrams as an extended view of nature. When seen through an objective or scientific lens, these images give us a wider idea of nature. I felt that these specific images could be re-specified within the context of the painting. Cezanne said that painting should “create a new optic of nature.” I was interested in that idea.

——Your paintings seem to show a micro world, or conversely, a world on a gigantic scale. Are you conscious of this multidimensionality and diversity of scales in your work?

Winters: I’ve always been interested in scale-free images. I’m after pictures that have a multiplicity of readings. The paintings are all actual sizes, but the depicted images don’t have a specific size or scale. I’m interested in that mobility. Creating an image that is fluid and abstract.

The paintings are made within a certain time frame and physical limitations, but the imagery can suggest a boundless dimension. I like that contradiction.

——I was impressed with the size of your paintings. In the contemporary art world, many paintings are excessively huge, but honestly, I am not a big fan of those. The size of your paintings has a moderate sensation of dimensions.

Winters: Because they are created in relation to the body. What is important is how the painted marks create gesture and touch set to a human scale, from the hand and the arm. This, in turn, helps to generate images that one can connect with and identify.

Buckminster Fuller, abstraction and architecture

——You mentioned earlier that you have been interested in images free from scale. This reminded me of the theories of Buckminster Fuller, a man of many faces, including theorist and architect. I think Fuller was a man who could traverse the microscopic world and the gigantic scale of the universe and see the common structures there. In other words, he did not care about actual size. I think he saw a world that transcended actual size, that was free from scale.

Winters: They are fractal structures.

——Exactly. The same is true of a truss structure where the members are connected in a triangular shape.

Winters: I’ve been a Buckminster Fuller fan since I was a student. I even attended one of Fuller’s lectures. He would talk forever. In a way, the length of his lectures was also free from scale [laughs].

Fuller is a great example of someone who started from natural forms, transformed them into technical tools, and sought solutions to various problems on the planet. There was an enormous amount of thinking and ecological thinking around his work. I felt a great deal of sympathy for that approach. And I see a similar attitude in Japanese and Asian aesthetics. Seeing art as “an imitation of nature in its operation.”

——Your paintings have been described as abstract. When I think of Fuller, his geodesic dome structures also seem geometric and abstract, but they are not abstract. They are directed toward the solution of a concrete problem. It seems to me that your paintings also address this problem.

Winters: That sounds right. I want to use abstraction as a process to make real-world pictures. Or, in some way, to use painting as the search engine, seeking resemblance. You mentioned Fuller, and I’m interested in architecture generally. All the modern disciplines, really. Music, literature, and film each have wrestled with issues of abstraction. Painting was in that 20th-century vanguard, and its trajectories still continue. Maybe we are approaching new phases of abstraction and representation. Especially since we now inhabit such an abstract world of bits and bytes disconnected from any concrete or corporal exchange.

——I have another question related to the previous one. Your paintings are generally considered abstract but also have a sense of concreteness. For instance, they seem to have an architectural structure that is not created by humans. Instead, the architectural structures in your paintings appear to be ubiquitous in nature and the physical structures of living things. Given this, would you consider the term “architectural” an appropriate way of describing your paintings?

Winters: That sounds true. But the architecture is, in fact, imaginary. It is a kind of vitalized geometry of inflections, vectors, and frames. Which hopefully gives a sense of life, a pattern language that speaks on many levels. Everything has patterns, even the invisible. And I think Fuller was tapping into those invisible structures and forces as models for his engineering. Painting can sometimes picture those forces as images of thought and feeling.

Aiming for paintings that are not merely aesthetic or arbitrary but become functional and necessary

——When we transcend scale, we can see structures in the world and nature that we could not see before. Earlier, you mentioned patterning systems, and we can see the pattern of dots in your paintings in this exhibition. I think painting and repeating such forms is also connected to the physical act.

Winters: Yes, painting is manual labor. The physical action of painting, just moving material around, contributes to how the image reads and what it means. How a painting is made is a big part of what it means. There is an unconscious understanding or reading on the viewer’s part - just in terms of construction, the material, and touch. It’s a feeling. And that’s a quality I admire in indigenous and folk art. I’m interested in how painting can engage contemporary forces and produce a physical artifact.

——Do you think your paintings’ material sensations and sense of physical actions psychologically affect the viewer?

Winters: I hope so. The pictures are painted to have an effect. An expression. Not necessarily in terms of self-expression but in what is expressed through that compound of source drawings, selected materials, manual skills, and emotional states. In the end, I want the painting to be a kind of instrument. Functioning as both a receiver and sender of signals.

Willem de Kooning said, “Even abstract shapes must have a likeness.” I think that sense of likeness indicates a connection to the world, even if it is difficult to articulate.

——In that sense, can you say that paintings also have concreteness and function?

Winters: I want my paintings to feel functional and necessary, so they do not remain purely aesthetic or arbitrary. Hopefully, the painting process follows all the necessary pathways. There is a term called “Creode” proposed by biologist Conrad H. Waddington. This is a concept used by geneticists and biologists with respect to evolution and cellular development, in which each body part of an organism follows a necessary pathway (creode) from its developmental stage to reach its final form. I’m also trying to set up a system or parameters for invention and improvisation. By following a method beyond myself, the painting can move towards some unforeseen productive completion.

——You mean a generative system?

Winters: Exactly. Although I am constantly involved in painting, I am paradoxically surprised by the results. I think historical figures such as Kandinsky, Miró, Gorky, Pollock, and Cy Twombly did the same; they invented and developed the genre. Painting is a very simple and primitive way to explore and address complex and current issues.

——All of these painters emphasized improvisation and spontaneous development, didn’t they?

Winters: That’s right. Basically, I don’t know what I’m doing either [laughs].

——In conclusion, your paintings seem to have a complex interplay between the intellectual and the visual. Could you share your thoughts on the relationship between both?

Winters: That was a critical issue, how to reconcile the two principle currents, or practitioners of modernism, namely Picasso and Duchamp: the retinal and the conceptual. For American painters, Jasper Johns helped open a space where those two conditions weren’t mutually exclusive. He unified those fields and cleared a new way for painting. In some sense, I’m operating in that territory, trying now to push the actual elements of painting toward the virtual dimensions of the imagination.

Terry Winters

Terry Winters was born in 1949 in Brooklyn, NY. He lives and works in New York City and Columbia County, NY. Winters has long held sympathies for Japanese art and has worked in Japan on two separate occasions, producing extensive print portfolios: Primitive Segments,1991, and Tokyo Notes, 2005. His work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions at museums across the United States and Europe, including the Drawing Center, NY, USA(2018); the University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA, USA (2018); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA (2017); Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark (2014); Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland (2009); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, USA (2001); Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland (2000); Whitechapel Gallery, London (1999); Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1998); Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, USA (1992); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA (1991); Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN, USA (1987); and Tate Gallery London (1986).