Art in Sleep and Dreams

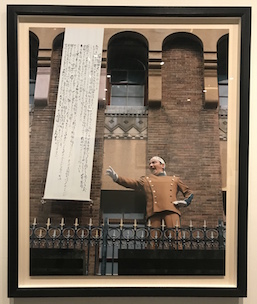

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo attempts to reveal the significance of sleeping, waking, and the experiences between them through the interpretations of artists in the exhibition “Sleeping: Life with Art—From Goya and Rubens to Shiota Chiharu.” An international mix of artists including Tsuguharu Fujita, Yasumasa Morimura, Francisco José de Goya, Odilon Redon, and Dayanita Singh illustrate how sleeping and dreaming influence our desires, doubts, and even our struggle to separate dreams from reality. Approximately 120 works have been collated in various media: painting, print, drawing, photography, sculpture, installation, and video to evoke the tremendous power of imagination that transpires from the moment we close our eyes to when we open them.

The exhibition dwells on the subjects of dreams and reality, life and death, sorrow, consciousness and unconsciousness during sleep, cycles of sleeping and waking, and the meanings of closing our eyes. One charming painting is Peter Paul Rubens’ Two Sleeping Children (c. 1612-13). The two innocent-looking dozers were believed to have been Rubens’ niece and nephew. Their father, Rubens’ brother Philip, was said to have been very fond of Rubens, and Rubens appropriately manifested this deep affection in the richness of the children’s skin and rosy cheeks, emphasized by tonalities of light and dark. The work depicts the state of quietness and peace during sleep.

In Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes’ etching Los Caprichos: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799), part of a series of 80 etchings published in 1799, Goya used the expression of sleep as a satire of the political, religious, and social abuses in Spain during the 18th century. He illustrates animals such as cats, bats, and an owl as monster-like beings that can prevail over reason when reason is asleep or numb. These were believed to be Goya’s own critical thoughts and that the human caricature portrays himself in resigned slumber and torment by prowling creatures. Human society is perennially afflicted by political conflicts, wars, diseases, crime, poverty, and natural disasters that incite anxiety and depression, and sometimes in the hour of helplessness, we take refuge in the comfort of sleep to pacify our unresolvable difficulties.

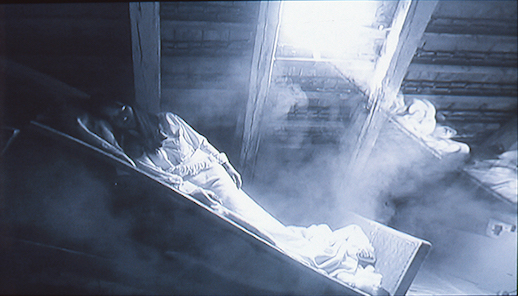

Some works invoke the state of sleeping or dreaming as indirect channels between life and death. For instance, the celebrated artist Chiharu Shiota has produced a single black and white video, Falling Sand (2004), depicting a mysterious woman lying in bed while a bag releases sand on to the bed, spreading a cloud of dust around the room. At one point, the woman disappears into the unknown. The viewer is left with the eerie sense of tranquility, and at the same time, fragility and insecurity as the sound of metallic chimes tingles in the background. Shiota’s work makes one ponder the line between the transience of life and the unsettling inevitability of death.

Finally, three huge video screens narrate the various dream experiences of Asian migrant workers based in Taiwan. Chia-En Jao’s REM Sleep (2011) presents individual monologues of 18 men and women who wake up from their sleep to relay their unforgettable dreams—many of which are sad tales about their families and children back home and testimonies of loss, pain, guilt, and fear. Their stories present proof that dreams serve as confessions of our inner desires and suppressed emotions buried during our sleep. Some of these dreams seem to surface in a more favorable reality than actual circumstances themselves, making us wish that we had not woken up. Art is, after all, a product of imagination and has, indeed, limitless power to impart visions, thoughts, and emotions, whether they arise from unconscious experiences during sleep or from consciously triggered events. Sleep can, therefore, either unlock our dreams through visually expressed pieces of memories, or shut them away so they remain untraceable.

Alma Reyes

Alma Reyes