Zero Degree Conditions

A former boxer and largely self-taught architect who learnt his craft based on a Grand Tour of mostly European and North American modernist masterpieces, Ando professes a deep admiration for and affinity with the “Big 3” of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. Some of Ando’s larger civic and museum projects recall the expansiveness and geometric grace of Corbusier’s buildings in Chandigarh, while others draw on Lloyd Wright’s truthfulness to materials. Ando’s most distinctive signatures are perhaps his facades of carefully poured and molded unfinished concrete, seeking a halfway point between concrete’s industrial cleanness and its organic, naturally uneven textural quality.

Guiding Ando’s use of concrete are certain basic principles: geometry, integration with nature, and dialogue with site. Surveying the some thirty works on display, only a handful of which have been reconstructed in maquette form, one is forced to admit that such bases are not particularly radical or unique – what architectural form does not emerge from geometrical measurements and proportions? Contextuality and environmental assimilation, too, seem now to be fairly universal objectives — which is why Ando might be said, in his rationality and reasoned approach to analytic building, to represent a certain catholicism. In the current architectural economy of attention and spectacle — and especially in the global starchitect arena where Ando now predominantly works — this exhibition serves as a timely reminder of architecture’s fundamental bases and its degree zero conditions, through a returned and sensible focus on the sites themselves.

An interesting and potentially problematic instance of faithfulness to these “bases” is Ando’s Church of Light (1989) in Ibaraki, a suburb of Osaka. The 1:10 model on display exposes and illuminates the structure of this building: it consists of an L-shaped shaft of concrete slotted at a dramatic diagonal angle through a thin slot in a rectangular concrete box with no other openings or windows. This dynamic wedging of a fissure is echoed in the way light enters into the building: through a cross-shaped lateral skylight carved into the far wall, the only gap through which light is able to slice the space.

Inspired by the similarly pronounced contrast between radiant illumination and dour gloom found in Romanesque churches, where light from outside is admitted directly in controlled doses into an inner sanctum, Ando intensifies the quality of that contrast by using only unfinished concrete, with its rough, variations-on-monotone texture. When clear winter light pierces the gloom and animates the dull, blank concrete canvas, the effect is no doubt ravishing — but what about the prospect of oppressive grayness during overcast weather? This purist approach and dependence on natural illumination, while making the Church prone to a tomb-like splendor on cloudier days, nonetheless remains faithful in a sense to Ando’s will to achieve integration with nature. To integrate is in part to enter into a relationship of willing co-dependence with the other variables; in this case, delegating responsibility for illumination to nature is to wager on its fickleness and natural variation. For each resplendent light-flooded afternoon, worshippers will have to endure sitting in the dark once in a while.

This purism comes through more clearly in the 1:1 wooden mockup of Ando’s first commission, the Row House in Sumiyoshi (1976), a low-rise, somewhat ramshackle shitamachi area of downtown Osaka. Ando renovated the middle unit of a set of three traditional merchant nagaya dwellings, almost completely gutting the long, slender site with a frontage of only two ken (3.64 meters). Out of a total site area of 57.3 square meters, Ando allocated a whole third of that to an internal courtyard situated roughly in the middle of the long plot, so that, thanks to its deep approach, one has the impression of broaching an inner private space even within this small site. Extremely simple in conception and, again, rendered entirely in unfinished concrete, the courtyard is both a rupture and a gap of reprieve in what could otherwise be an oppressively enclosed space. The rectangular courtyard measuring about 24 square meters is divided lengthwise, from left to right, into three sections: opening, corridor (connecting the two rooms on the upper floor), and open-plan staircase leading upstairs. According to Ando, looking up through the opening while seated at a patio table in the courtyard, one “feels the wind”, a connection to nature graspable even in this severely “land-locked” situation. In urban areas with sticky restrictions on space and cost, it is especially imperative to prioritize not just convenience and cheapness, but to try to create a space in which one can dwell with visible lines of flight toward what nature remains glimpsable in the city.

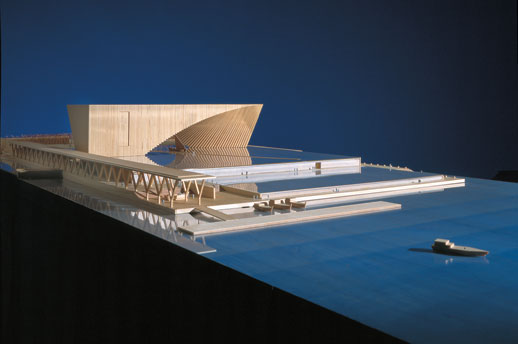

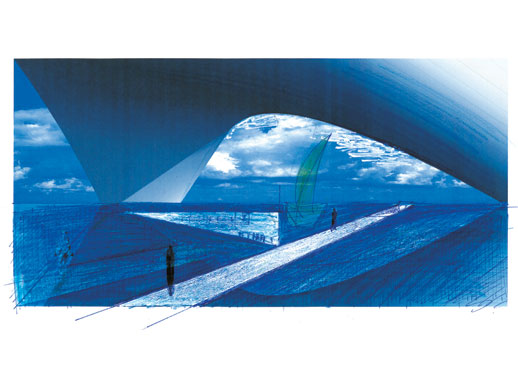

One questions how much of a sound application of Ando’s founding principles could be fruitfully applied to the gigantic scale of a project like the Abu Dhabi Maritime Museum, or the massive underground transit project to thread through the new Fukutoshin subway line in Tokyo. It is his smaller commissions — individual dwellings, temples and churches and museums — where his “bases” are more easily applied and appreciated.

Apart from these two signature works, there are several other less elaborate architectural models of more recent international projects, notably for the monumental wave-like Maritime Museum in Abu Dhabi and a university building in Monterey, New Mexico. These massive projects testify to Ando’s stellar reputation as a top international architect, but also to the rapidly burgeoning scale of his work that has forced him to adopt shifting positions and approaches to the integration with nature. This integration comes across more clearly in his earlier, smaller buildings — including a number of provincial art museums in Japan, like the Water Temple on Awaji Island. Nonetheless, in its selection of both smaller and larger commissions, this exhibition is a comprehensive showcase of the applications of Ando’s “bases” across a wide range of contexts and site conditions.

Darryl Jingwen Wee

Darryl Jingwen Wee