Urameshiya: The Art of the Ghost

The Japanese tradition of Hyaku Monogatari (The One Hundred Stories) gathers people in a room lit by 100 candles to exchange ghost stories. A single candle is extinguished at the conclusion of each tale in encroaching darkness, and when the last story is recounted and the final candle put out, it is said that a ghost will appear. Though typically little more than a parlor game, particularly during its peak in the late-Edo era, this storytelling practice must have retained a touch of something moving, almost solemn – not just because it creates a passage between light, the living, and language on the one hand and darkness, the dead, and silence on the other – but because the former seems like a ceremonial preparation for the latter. One thinks of Walter Benjamin’s observation that “death is the sanction of everything that the storyteller can tell.”

One such storyteller was Sanyutei Encho, who, aside from his status as one of the most famous rakugo performers of the Meiji era, specialized in tales of ghosts and the supernatural. His private collection of hanging scrolls normally kept at Tokyo’s Zenshoan Temple is currently on display at Tokyo University of the Arts’ University Art Museum, comprising one half of the exhibition “Urameshiya: The Art of the Ghost.” From this name alone (uramu means “grudge”), we might expect to encounter spirits racked with rage and anguish wreaking malice. While several of the works conform to this expectation, the majority of the subjects seem pitiful, absorbed in an obscure grief or resigned to a fate by which they are still bewildered. Looking at them, we feel less like spectators and more like intruders – they seem meant for the private, reflective gaze, with little narrative action and colors used sparsely if at all. Considering that over 20 artists contributed to Encho’s collection (the actual number is probably higher, since a number of the paintings are anonymous), there is a remarkable atmospheric unity among the works, likely due to many of the scrolls having been commissioned by Encho himself. In some cases, artists have abandoned their usual styles to appease Encho’s sensibilities. Gekko Ogata, for instance, forgoes the delicate and nuanced shading evinced in his woodcut prints and creates something much more minimalist – a portrait composed of a flurry of dark, calligraphic strokes that appear rendered with great speed and confidence.

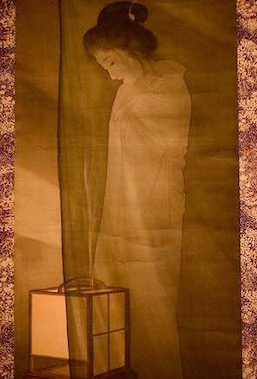

The ghosts in these works are usually accompanied by objects suggesting lightness and transparency – spider webs, mosquito nets, screens, wisps of flowers, streams of water, moonlight – but there are no interactions with the living, for ultimately they are creatures of solitude, more haunted than haunting. One of the most exquisite scrolls, Eiho Hiresaki’s ‘A Ghost Before a Mosquito Net,’ shows a woman standing with a lamp and mosquito net in a bedroom. At first this scene appears to simply be a melancholy but intimate portrait of a woman: her hair is bound up neatly, she has her youth and beauty, her self-possession. We only see she is a ghost when we realize that we can not place her exact position, that her pallor matches the luminous white of her funereal robe blending into the shadows as it falls; but then “ghost”, with its connotations of spookiness and haunted-house horror, seems the wrong word. For her, and for many other paintings in this collection, “apparition” is perhaps more appropriate. Hiresaki presents the ghost not as a vessel of consuming passions but something more tender and refined, as though her existence is possible only through a certain interplay of shadows and light, and she herself might be extinguished along with the lamp before her.

Hiresaki created this scroll in 1906, when the popularity of the supernatural had already begun to dwindle. But we may wonder about earlier images and what works intended for a more public consumption would have looked like. The other half of “Urameshiya,” devoted to the lineage of uramu in the 19th century, answers these questions.

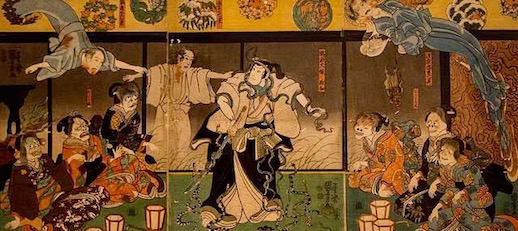

Pictorial representations of ghosts in Japan first found widespread popularity in the ukiyo-e paintings of the first half of the nineteenth century. These paintings capitalized on the popularity of ghost stories in the kabuki performances of the day, and some were even direct depictions of these performances. “Urameshiya” has collected over 40 such paintings, most done by some of the most famous ukiyo-e artists including Hokusai, Kuniyoshi, Tsukioka, and Toyohara. Here our initial expectations for the exhibit are met: compared to the Encho collection, in these works the colors are richer, the drama more obvious, the grotesque elements of gore and disfigurement more emphasized; we are not dealing with “apparitions” so much as the undead. They streak in through walls, swarm ships at sea, scowl menacingly from fires; they are, in one sense, lively.

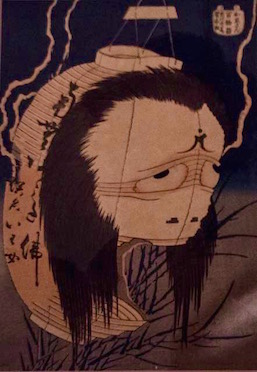

A benefit of a thematic collection such as this one is that the viewer can compare the different manners in which artists handle the same subjects. For instance, Yoshitoshi Tsukioka’s prints from the ‘100 Views of the Moon’ collection are serene and meditative, drawn with a clarity and intimation of symbolism reminiscent of certain tarot cards or old-fashioned frontispieces. (Tsukioka was also known for painting gruesome scenes from famous murders; sadly, none of them are on display here). Meanwhile, Kuniyoshi appears drawn to moments of trespass, when the sanctity of the home has been violated, and Hokusai seems more interested in purely figural possibilities: the way a disembodied force can manifest itself in the objects it haunts.

We can see these differences in Kuniyoshi and Hokusai’s depictions of the climactic scenes of one of the most popular ghost stories, the Yotsuya Kaidan. In this tale the vengeful ghost of the Lady Oiwa reappears in a hanging lamp before her husband, who had attempted to murder her with a poisonous topical cream that left her face mutilated beyond recognition. (The poison eventually succeeded in killing her, albeit indirectly – she committed suicide, as much from shame as the heartbreak of betrayal by her husband). Kuniyoshi draws this scene again and again, each time trying to fix both the invariably deformed face of Oiwa in her moment of intrusion and her husband in his own terrified reaction. Hokusai, on the other hand, portrays only the lamp, which has merged with Oiwa’s head (a portrait or a still life?), her eyes sagging between its blinds, her mouth not so much drawn as implied in the gaping hole where the lamp has shattered.

Still, the images are not always this gruesome. Encho’s most famous story, ‘The Peony Lantern’, ends with the deceased main character in his bedroom, locked in the embrace of a skeleton that appeared to him in the guise of a former lover. If intimacy with the dead is something of a trope in ghost stories, it is because a ghost provides an ideal figure in which to mingle the forces of death and sexuality. Even in the exhibition’s oldest painting, an 18th century work by Maruyama Okyo, there is an intimation of tenderness and beauty. In the early 1800s, uramu-type ghosts (almost always female) came to be modeled on bijin-ga portraits of beautiful women, a development that gained further traction in the second half of the nineteenth century, when ghosts garnered enough popularity to stand apart from stories that at times skewed towards the cartoonish and sensational.

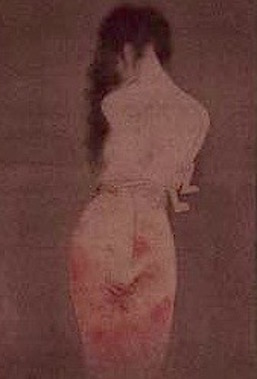

Thus, in addition to the ukiyo-e prints, the exhibit also displays works that register the allure in even the most bitter of ghosts. The hanging scroll painting ‘Demon Ubume’ by Tsukioka, depicts an ubume, the ghost of a mother who perished giving birth. Traditionally this figure was represented as an old crone pressing her child against her shriveled breasts, made miserable by her inability to succor her child. Tsukioka’s version, however, is suffused with eroticism – the ghost’s bare back is turned toward the viewer, her lithe white body swaying in the darkening fog.

In spite of this eroticism, there remains a certain distance, like something glimpsed in the half-lights of memory; the ghost’s back is turned, she is already fading. It is fitting that this painting comes near the end of the exhibit – while its works portray how the dead make their returns (sometimes abruptly and violently, sometimes timidly, here plain and unadorned, there in the guise of others) – they ultimately show us that this is also the only way the deceased have of disappearing.

Parker Thomas

Parker Thomas