Traumatic Reflections

“Wounded Cities” is Leo Rubinfien’s third Tokyo exhibit of 2011, which perhaps shouldn’t be much of a surprise: apart from spending time here as a child, Rubinfien has been exploring cities through his candid photographs for more than 30 years. His show earlier this year at Taka Ishii (“Leo Rubinfien”) suggested that all large cities are alike, while his Kurenboh exhibit (“The Ardbeg”) studied the faces of individuals in these cities. “Wounded Cities,” at Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art through October 23, makes it seem like these two previous shows were only laying the groundwork for this current exhibit. “Wounded Cities” is a series of photographs from large cities all over the world—Moscow, London, Seoul, Karachi, Colombo, and so on—and like the Kurenboh show, he’s shooting faces rather than urban landscapes. But with this show, Rubinfien is trying to say that not only are all cities alike, but that they are alike in the way that they have been traumatized by terrorism, particularly in the wake of 9/11.

In the cheap and excellent catalog of the show, Rubinfien writes that he’s trying to find faces that “speak for the condition, in the terror era, in which I found myself living.” This seems a tall, if not impossible order for photography to fill. How is it possible to capture a psychological trauma through photography? Much to his credit, Rubinfien is fully aware that this project pushes up against the technical limits of his medium. He goes on to write that he realized: “if I were going to make a book, it would need a piece of writing as well.” The book was eventually published by Steidl in 2008, and the first chapter of Rubinfien’s extensive text is reproduced in the catalog. These words do heighten the effect of the photographs, even though the show is compelling on its own.

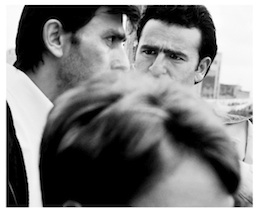

“Wounded Cities” could be displayed without a statement and still hold up as a very strong body of street portrait work. The exhibition features thirty-five different close-up, unstaged portraits taken on the street, all printed at a larger-than-life size, all but three shot in black-and-white. Above all, Rubinfien seems to be looking for something in the eyes of his subjects. Sometimes the person in the foreground is looking away from the camera, while a blurred figure in the background is looking right at him. Eyes hide behind the reflection of glasses, dart (furtively?) outside of the frame, coolly meet the gaze of the lens, stare off into the distance, look down. There are no walls in this exhibit; the photographs have all been hung directly from the ceiling on wires with gaps in between. Walking through the rows of photographs, an eye (or two) across the other side of the gallery jumps out at you. It’s almost more powerful to look at the faces in this way: from afar, framed by the prints in between, a single eye cutting right through the distance.

But for all of their photographic merits, Rubinfien is telling us that his photographs represent something greater. He is trying to step into the flow of history, although it’s not really clear which direction he’s looking—is this a guess about where we’re heading, or an attempt to understand what’s happened to us? In any case, to a large extent the photographs can only work if you accept Rubinfein’s proposition (or opinion) that the residents of Buenos Aires and Tokyo and Moscow are as equally traumatized as the residents of New York City—or, to be more specific, as much as Rubinfien himself. It would be unfair, if not impossible to write about this work without mentioning the fact that Rubinfein was two blocks away from the World Trade Center on 9/11, in an apartment he’d just purchased. That Rubinfein had to write so many words about “Wounded Cities” indicates that this work is a way for him to continue processing this experience. For now, this text is necessary to spell out the psychological motives behind the photographs, but perhaps later the images will acquire the ability to speak for themselves. What such a development might mean, though, is impossible to predict with any certainty.

But for all of their photographic merits, Rubinfien is telling us that his photographs represent something greater. He is trying to step into the flow of history, although it’s not really clear which direction he’s looking—is this a guess about where we’re heading, or an attempt to understand what’s happened to us? In any case, to a large extent the photographs can only work if you accept Rubinfein’s proposition (or opinion) that the residents of Buenos Aires and Tokyo and Moscow are as equally traumatized as the residents of New York City—or, to be more specific, as much as Rubinfien himself. It would be unfair, if not impossible to write about this work without mentioning the fact that Rubinfein was two blocks away from the World Trade Center on 9/11, in an apartment he’d just purchased. That Rubinfein had to write so many words about “Wounded Cities” indicates that this work is a way for him to continue processing this experience. For now, this text is necessary to spell out the psychological motives behind the photographs, but perhaps later the images will acquire the ability to speak for themselves. What such a development might mean, though, is impossible to predict with any certainty.

Dan Abbe

Dan Abbe