The Sight-Sound Connection

Internationally renowned composer and musician Ryuichi Sakamoto is the General Advisor of the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo’s latest grand scale exhibition, “Art & Music – Search for New Synesthesia”, the third installment of the Tokyo Culture Creation Project’s Tokyo Art Meeting program.

As a general rule, art and music have long been recognized as independent disciplines, to be studied under separate faculties and experienced as two discrete pleasures. Take Sakamoto’s university for example, Tokyo University of the Arts (formerly Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music). It was established in 1887 with two specialist schools, Tokyo Fine Arts School and Tokyo Music School. Finally merged in 1949, this is a period that coincides with the first phase of the academic ‘synesthesia boom’. Meanwhile, artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, whose works are featured in this exhibition, had been exploring connections between art and music since the 1910s.

The recently closed “Debussy, Music and the Arts” held at the Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo looked at nineteenth and early twentieth relations between musicians and painters. It focused on working collaboration and interdisciplinary production. The NTT InterCommunication Center in Shinjuku has hosted more contemporary investigations into the area, with exhibitions such as “Sound Art, Sound as a Medium of Art” (2000) and “Silent Dialogue” (2007). However, the current exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo takes quite a different approach, exploring the sensory phenomenon that can occur when experiencing art and music: synesthesia.

![Photo: Ryuichi Maruo (YCAM)

Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [Reference Image] Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani, 'LIFE - fluid, invisible, inaudible...' (2007)

Commissioned by Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM)](http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/art-music-search-new-synesthesia-1.jpg)

According to Hiromoto Makabe, we are currently seeing the second boom in this area of investigation, which originally developed around mysticism and the educational practices of artists and musicians (such as Bauhaus), but has now been re-rooted in contemporary psychology and the scientific study of brain function. To put it succinctly, it is “the output of associative or metaphoric images by the various sensory organs operating in an integrated manner.”1 So, think of the connections our brains sometimes make between the different physical senses, and then the mental reactions that are forged as an effect of these ‘seeing’ and ‘listening’ to encounters.

Featuring twenty artists/groups, this exhibition places works almost a century old alongside brand new pieces. It combines works by musicians as well as multimedia creators and visual artists, including participants from nine different countries. Sakamoto collaboratively produced two new pieces for this exhibition, and they can be found adjacent to one another in an expansive, dimly lit space near the start. The first is a collaboration with Dumb Type member Shiro Takatani and sound designer Seigen Ono entitled ‘Silence Spins’ (2012). Speaking as part of an artist-led tour on the opening day, Sakamoto described how the work was inspired by traditional Japanese tea-ceremony room design. The viewer is encouraged to remove their shoes and step up into the small, unlit black room to move around it freely. Created from ‘shizuka stillness panels’, the idea is that one can hear the infinite universe from within this door-less enclosure, sounds ranging from those created by the circulation of our blood through to noises in the external environment.

![Photo: Ryuichi Maru. Courtesy of Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo Ryoji Ikeda, 'data.matrix [n°1-10]' (2006-09)

© 2009 ryoji ikeda](http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/art-music-search-new-synesthesia-2.jpg)

Currently this includes the sounds created by Sakamoto’s second collaboration, ‘Collapsed’ (2012). Taking up a large portion of the space, two Perspex-topped pianos are positioned across from each other, a laser projection system located between them. As Sakamoto explained, these lasers project extracts of philosophical texts upon the walls. The English-language texts are translated into musical data via computers and played back on the pianos. On the subject of how written language may be translated into music, Sakamoto pointed out the challenges that arise between the numeric discrepancies between the 26 letters of the Roman alphabet, the 44 characters of the phonemic chart, and the 88 keys on a standard piano. This piece could be said to pick up from where Michi Tanaka and Jiro Takamatsu’s ‘The Language Instrument Parole Singer’ (1974), also featured in the exhibition, leaves off with its typewriter-piano keyboard where music is composed by ‘typing’ in katakana.

Two rather discrete but fantastically paired pieces right in the middle of the exhibition are Bartholomaüs Traubeck’s ‘Years’ (2011) and Lyota Yagi’s ‘Vinyl’ (2005). Both addressing time, they take unique approaches to representing the metaphorical ticking clock; one minute of one of Traubeck’s wooden records translates to twenty years passed, whilst Yagi’s ice records, comparatively quick in the making, have a limited lifespan once they are set to play.

Viewable from both levels of the exhibition, Otomo Yoshihide limited ensembles’s ‘with “without records”’ (2012) is an impressive sprawl of analogue vinyl players, each ‘modified’ so that they no longer need vinyl to create music. The visual impact of this is arguably equalled by Ryoji Ikeda’s impressively modern multi-projection audiovisual installation ‘data.matrix [no 1-10]’ (2006-2009).

![© Celeste Boursier-Mougenot. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Photo: Isabella Mathgus [Reference Image] Installation view from Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, 'Variation, Pinacoteca, São Paulo, Brazil' (2009)](http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/art-music-search-new-synesthesia-3.jpg)

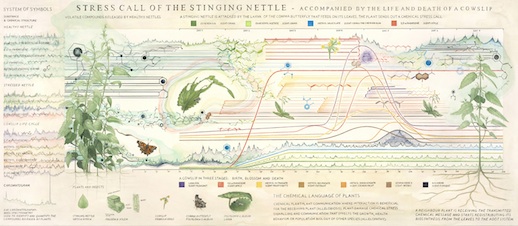

An interesting theme in this exhibition is the apparent divide between many of the works, which seemingly side either with a scientific or emotional approach. Carsten Nicolai utilises differing frequencies of sine waves to demonstrate the very concrete connection between acoustic signals and visual patterns. Concentrating upon groundbreaking biological research, Christine Ödlund has created an AV projection as well as minutely detailed illustrations and diagrams demonstrating the use of language and signaling between plants. In contrast to this, Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s ‘Clinamen’ (2012) is a poetic acoustic piece created in response to her personal questions. Udomsak Krisanamis’s room of rhythmic paintings, including ‘Four some’ (1999) and ‘Don’t Go Near the Water’ (2012), appears to be similarly personal as each title suggests.

From the plethora of diverse works gathered here it is evident that what each of the contributors share is a common search for a new perspective. The creators are not striving to discover something new factually speaking, but rather they are aiming to find ways to make things we are already aware of newly visible or audible, so that our experience of them may be altered. With this we may be able to move away from the “human-centred control myth,” as Sakamoto expresses it in the exhibition catalogue, and broaden our catchment so that we return to a macrocosmic perspective that allows us to recognise our position in the world more accurately.

Jessica Jane Howard

Previously a resident of rural Shizuoka, Jessica has just moved to Tokyo for the first time, following the completion of a Masters in 20th-century avant-garde art history back in the UK. Before living in Japan initially, she worked in English museums and art galleries assisting with collection research, exhibition planning and events organisation. Since arriving back in Japan in September 2011, however, she has been working as a film screener for a Tokyo-based film festival and as a freelance semiotician. Her interests span far and wide, ranging from feminist politics in the visual arts to South Asian pop culture. An obsession with 20th-century Japanese print culture, magazines in particular, is also worth noting. See other writings

Tokyo Culture Creation Project

Tokyo Culture Creation Project