To India: Chalo!

When I spent six months in India a few years ago, chalo (‘let’s go’) was the first Hindi word I learned. This was in Mumbai, where I more often heard English then Hindi, not just as a courtesy to myself but because our crowd was made up of Indians from all over the subcontinent and the world. For this mobile society, having arrived from the north and south, London and New York, Hindi was as much an additional tongue as English. Chalo, however, everybody used; there is just something about this singular call to action that rolls off the tongue more easily than its English counterpart.

With the Mori Art Museum’s latest exhibition, “Chalo! India: A New Era of Indian Art,” the Tokyo art world is invited to India to see for themselves the energy and momentum implied by the title’s first word. This comprehensive exhibition is an effective primer on art in modern independent India, introducing twenty-seven contemporary artists. Several of those represented made up the Baroda School in the ’60s and ’70s, while others were born at the tail end of those years and into an India increasingly active in the global economy and the IT industry. The artists mainly come from four major centers: Dehli, the historical cultural and intellectual capital; Mumbai, the economic frontier and larger-than-life setting of Bollywood; Bangalore, the IT hub; and Vadodara, the home of one of India’s most prestigious fine arts programs.

The sprawling show is itself divided loosely into sections, starting with the prologue “Journeys,” continuing through “Creation and Destruction: Urban Landscapes,” “Reflections,” and “Fertile Chaos,” before the epilogue “Individuality/Collectivity, Memory/Future.” This progression mimics, in a way, an actually journey through the subcontinent, making the call of chalo all the more pertinent.

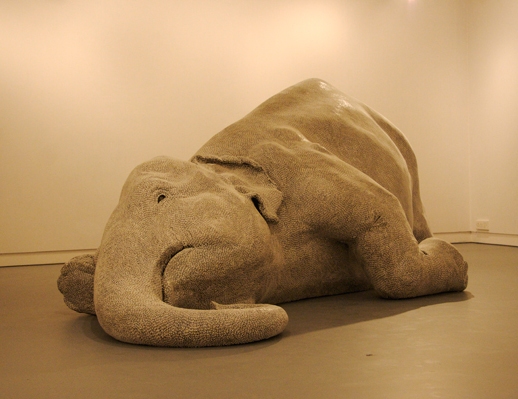

At the starting point of the exhibition visitors are confronted and first seduced by two large works by Bharti Kher that make heavy use of well-known cultural icons: images of the elephants and mandalas of travel posters. We are then induced to pass through Gulammohammed Sheikh’s portable shrine, a one-room fold-up schoolhouse whose walls portray scenes and figures from Indian history and mythology. Beyond these lessons from the past lies the India of the present and the future, a land that is a visual feast. But it is one that also wrecks havoc on neat dichotomies (urban/rural, spiritual/material) and ultimately offers visitors more varied experiences than they originally had in mind.

For example there is Shilpa Gupta’s ‘Shadow Piece’, a giant screen not unlike the millions around India devoted to the cult of Bollywood. This one however distorts viewers’ silhouettes into the stuff of sci-fi movies, by way of shadowy projections of scraps and debris that adhere themselves maniacally to human forms.

For example there is Shilpa Gupta’s ‘Shadow Piece’, a giant screen not unlike the millions around India devoted to the cult of Bollywood. This one however distorts viewers’ silhouettes into the stuff of sci-fi movies, by way of shadowy projections of scraps and debris that adhere themselves maniacally to human forms.

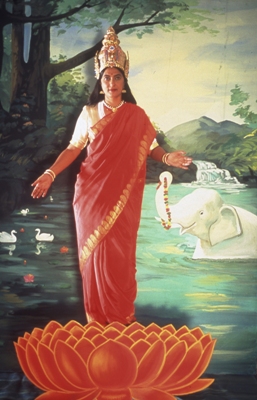

Another female artist, the Bangalore-based Pushpamala N., turns her critical eye to the legacy of colonial ethnography (and the more recent amateur anthropology of camera-wielding travelers) with a series of self-portrait photographs that interpret traditional and modern – but no less stereotypical – images of Indian women. Had this been a literal journey to India, many visitors would be ‘guilty’ of taking similar photos, like the sari-clad woman on the back of a motorcycle, talking on a mobile phone.

Meanwhile, Tushar Joag offers a new breed of art activism in the form of projects that span real space and gallery walls, using comic book-style paintings (and a pointed letter-writing campaign) to illuminate some of the idiosyncrasies and inconsistencies of life in Mumbai. And not one but two artists, Vivan Sundaram and Hema Upadhyay, offer visual treatments of their respective cities, Dehli and Mumbai, constructed from trash found on city streets. The work of the latter, a bas-relief of Mumbai’s famous Dharavi slum in tin cans and scrap metal, is poignantly displayed over a window looking out onto the Roppongi night scene. This use of found objects from street-level India is, in fact, a noticeable thread throughout the exhibition, with tin milk jugs, rubber stamps, textile scraps, and movie posters becoming sculptures, paintings, and collages.

Meanwhile, Tushar Joag offers a new breed of art activism in the form of projects that span real space and gallery walls, using comic book-style paintings (and a pointed letter-writing campaign) to illuminate some of the idiosyncrasies and inconsistencies of life in Mumbai. And not one but two artists, Vivan Sundaram and Hema Upadhyay, offer visual treatments of their respective cities, Dehli and Mumbai, constructed from trash found on city streets. The work of the latter, a bas-relief of Mumbai’s famous Dharavi slum in tin cans and scrap metal, is poignantly displayed over a window looking out onto the Roppongi night scene. This use of found objects from street-level India is, in fact, a noticeable thread throughout the exhibition, with tin milk jugs, rubber stamps, textile scraps, and movie posters becoming sculptures, paintings, and collages.

If you’ve made it this far perhaps you are wondering, is this an art exhibit or a very visual lecture on contemporary Indian society? Surely not every noteworthy artist in India is so concerned with the country itself, and the nature of Indian-ness? This is an important question and one that the exhibition may not answer, but I believe can be seen being worked out by individual artists, many of whose careers are just beginning to pick up steam.

The Mori Art Museum exhibition comes off a succession of shows on contemporary Indian art in the last few years—at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts, Paris and the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland to name two. The first decade of the new millennium has proved a boon for artists in the subcontinent, and not least of all at the auctions. While “Chalo! India” would seem to transport Tokyo museum-goers to another world for an afternoon, the exhibition itself is also indicative of the significant journey around the globe that these creators of the ‘New Era of Indian Art’ are in the momentous act of undertaking.

Rebecca Milner

Rebecca Milner