The Yebisu International Festival for Art and Alternative Visions 2016

The 8th Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions (Yebizo) took place at Yebisu Garden Place and satellite spaces around the Ebisu district February 11th through 20th. With exhibits, film screenings, performances and talks from over 80 artists, this year was no exception in the challenge of gaining a full perspective on this leading festival of media and moving-image work. Four TABlog writers attended the “Garden in Movement” themed exhibitions and here offer their perspectives on the show’s diverse displays.

Ryoto Kuwakubo’s The Tenth Sentiment

By Parker Thomas

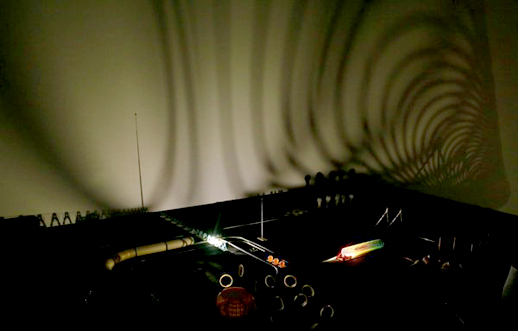

For the first few moments, hardly anything of Ryoto Kuwakubo’s installation “The Tenth Sentiment” can be seen, as the room is virtually pitch black. Then, two toy trains equipped with LEDs and positioned on different sections of a track winding around the room begin to move, slowly making their way through the darkness with a soft whirring like that of an old film projector. The sound is appropriate, for the LEDs pass over objects along the track, projecting their amplified shadows onto the walls.

In the Platonic allegory, the shadow on the wall is an illusion, a more ontologically diminished version of the thing itself. “The Tenth Sentiment” might be viewed as a reversal of this, for here it is the silhouettes that possess far more scope and expressive power than the humble objects casting them. An overturned colander becomes, as the train approaches it, a monumental and vaguely terrifying tunnel; perforated wastebaskets and threaded clothespins transform into silos looming over an unending line of transmission towers; toy men on a platform turn into, well, bigger men on a bigger platform. The images begin as small figures on the horizon, zoom into focus, and then disappear to make way for the next. There is no discernible narrative to this shadow-pageant, nothing to connect them but the movement of the train and the persistent sense of distance and loneliness, of uncertainty, of things passed or passing. Yet it is a testament to the archetypal power of these fleeting vistas that nearly all of them corresponded, obliquely albeit powerfully, to distinct images from personal memory, usually gazed at through the window of a car or train, or perhaps in a dream dormant for years.

When the train reaches what one surmises is the terminal station, it halts briefly before running backwards at a much greater speed, not unlike the way memory is said to unlock at the moment of death and replay itself in its entirety. And then the train begins again.

The Other Side of the Glass

By Jennifer Pastore

Chinese and Japanese ink paintings are widely recognized for depicting humans as details within landscapes, rather than positioning them as front-and-center subjects. This year’s Yebizo attempted a similar approach, spotlighting video and media art purported to have an ecologically expanded viewpoint. The results proved mixed, however, which is perhaps the inevitable result of choosing the “garden” – by definition a space of human intervention – as the central metaphor for reappraising people’s relationship with nature.

Among other works, Yumi Sasaki and Dorita’s Bug’s Beat (2016) illustrates the muddled message of the festival. This installation places insects of various shapes and sizes, from tiny roly-polies to the mighty stag beetle, in glass-encased platforms with microphones attached to fake leaves projecting the sounds the bugs’ movements. The auditory experience is meant to invert the viewer’s perceptions, shrinking her down to microscopic size in an alternate universe where the scurrying of bugs thunders in the ear. It’s an interesting concept, but the work ultimately cannot override the reality of its design. In the end, we’re still the ones towering over trapped little creatures undoubtedly wanting nothing to do with our machinations, creative or otherwise.

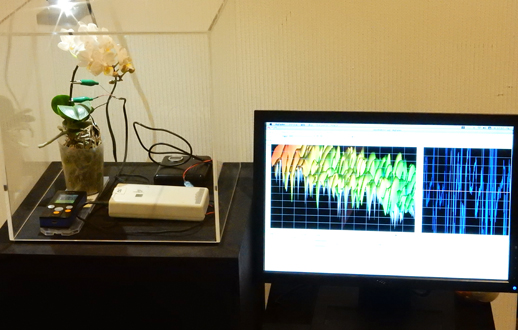

There were a few works that managed to overturn, or at least skew, the wisdom of the “humans as rulers of nature” narrative. Yuji Dogane’s Radio Active Plantron (2011) literally gives nature a voice by converting the biological feedback of plants exposed to radiation into sound. Although similar to Bug’s Beat, this display succeeds in prompting us to reassess humanity’s place and actions in the world by offering up something closer to a warning than entertainment. There was also Zhou Tao’s video Blue and Red (2014), which naturalistically observes people against backdrops looming larger than themselves: in Guangzhou, the foreboding artificial glow of enormous outdoor LED screens; in Bangkok, a violent crackdown on anti-government protests. Not only are the people in the footage not in control of their environments, they find themselves subjects of the ominous forces that have moved in to take nature’s place.

It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)

Discourse on disasters and ecological collapse has been a theme of art exhibitions and public conferences lately, one of them being the recent Yebisu International Festival for Art and Alternative Visions (Yebizo), subtitled “Garden in Movement.” This series of exhibitions, film screenings, and events in collaboration with institutions surrounding Yebisu Garden Place featured thought-provoking works from several fields that let us look at the world from what the catalogue describes as a “non-human centric” angle.

The philosopher and horticulturalist Gilles Clement made this non-human domain the focus of his gardening principles, observing plants and other organisms that thrive in wastelands without human intervention. As the natural world is nigh on fully enslaved to human control, Clement points out the shift of nature to the spaces which have been rejected by “development,” moving to undetermined sites left by the wayside of technological evolution and thriving in biodiversity beyond exploitative hands. This year Yebizo took this notion of gardens in motion as its curatorial framework, creating a viewing experience that was nomadic and transitory.

That dynamic element of Clement’s garden theory suggests the near future will be migratory. In fact, due to the rising sea levels triggered by our insatiable anthropocentric behavior, environmental refugees have become an inevitable reality, an uncomfortable truth that continues to be ignored owing to its inconvenience and bewildering threat. Nevertheless, Yebizo leads us, to some extent, to navigate this discourse.

The reality of looming ecological collapse apparent in our contemporary society presents an unbearable situation for mankind. However, human beings have the capability to endure traumatic experiences due to our innate ability to adapt in difficult conditions. No wonder, as part of our adaptability, we can easily ignore or transcend trauma without knowing the danger ahead. For its part, “Garden in Movement” reflects our contemporary ecological status yet paradoxically denies what led us to this disaster.

Ryota Kuwakubo’s “The Tenth Sentiment (2010)”, an installation of objects, lights, and shadow in a darkened room of La Maison Franco-Japonaise, illustrates this denial of trauma. Here we are led upon the track of that symbol of industrialization, the railroad; a train weaving in and out of the flicker of light and shadow casts familiar objects into immense renderings of the “Metropolis,” yet is completely devoid of reference to the natural animate world from which it sprung. The allure of this hypnotic shadow play sustains our ongoing desire for utopian promise while ignoring its apocalyptic consequences.

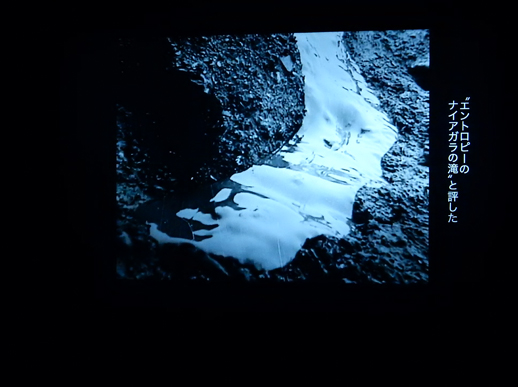

This denial of the disastrous effect of utopian promise is apparent also in Robert Smithson’s “Floating Island to Travel Around Manhattan Island” (2005), a video from 1970 in which Smithson, inspired by Central Park designer Fredrick Law Olmsted, conceives of and documents a floating garden escaping the confines of a doomed land to bring cultivated nature to any location. As a land artist, Smithson is known for examining entropy in his works by intervening in natural habitats or man-made sites, as in his monumental piece “Asphalt Rundown (1969),” a quarry dumped with hot asphalt. His works define the aesthetics of the open pit mining and garbage mountain dumps that modern utopian society generates in the attempt to disregard rather than accept the fact that we have breached the limits of our finite resources. If we fail to recognize the resulting trauma thrown open by our utopian pursuit towards the transcendence of the gap between man and nature, which Clement tries to reconnect, then we only move further towards ultimate breakdown and collapse. In its very denial of this condition, this exhibition allows us to see, to some extent, this missing fragment in the understanding of our contemporary ecological status.

Video Earth Tokyo “Under a Bridge” (1974)

By Emma Ota

In continuing the metaphor of Gilles Clement’s “Garden in Motion”, Video Earth Tokyo’s early production “Under a Bridge” points not to the survival of nature in the abandoned sites beneath mankind’s achievements of progress, but rather the endurance of humanity itself within such spaces. The grainy black and white video, from some of the earliest commercially available video cameras of the era, follows an encounter between Video Earth Tokyo founder Ko Nakajima and a homeless man living beneath a highway bridge. Created as a convenient shortcut across river borders, literally rising above nature, the bridge gives affordance to the ever-accelerated pace of life and the endless circulation of gas-guzzling traffic. Beneath this platform of advancement lies a forgotten land, a wilderness shunned by “civilization,” but a space of refuge for one left out of this “growth.” An alternative ecology is to be uncovered here beyond the eye of urban expansion, nurturing itself like Clement’s plants in the wayside.

The video begins in a violent confrontation by the two protagonists, in a collision between worlds that reveals the inherent aggression of photography/video. As an inhabitant of the so called “over-ground” infiltrates the territory of the “underground,” there is immediately a sense of threat, the homeless man bombarding the cameraman with a barrage of verbal abuse as he accuses him of being a thief come to steal from one who, for all intents and purposes, has nothing. Yet after a time the video subject begins to soften and commences an earnest reflection upon his life, his war-time experiences and traumas, and his methods for survival in his current state. The political message of “Under the Bridge” is clear, calling us to turn our eyes towards an existence we all too willingly ignore and confront our own complicity in it. The video also makes uncomfortable viewing due to the inevitable objectification of this “outsider” via the camera, and a sense of intrusion into a private space of hardship which might verge on so-called “poverty porn.”

This piece of video art history seems particularly pertinent at a time when Tokyo is undergoing another upheaval in preparation for the 2020 Olympics, readying itself to bulldoze and rebuild upon spaces deemed superfluous to requirements, including the public housing complex near one of the Olympic sites, which was paradoxically first built in conjunction with the 1964 Olympics. This is further coupled with the eviction of homeless people from various public spaces and “gaps” in the urban framework. We might also see here a parallel with the condition of refugees, particularly those in Greece and northern France in recent months denied access to their preferred place of refuge and forced to seek shelter in wastelands, putting together camps or shanty towns from whatever resources they can find amongst pools of mud and scrubland. The naming of the notorious, and now largely demolished Calais camp, “The Jungle,” appears to be fully in line with Clement’s “Third Landscape,” an unruly terrain on the outskirts in which nature might return to its primordial state and human life must struggle to survive.

Video Earth Tokyo was a pioneering video group established by Ko Nakajima in 1971. Taking on a lecturing position at a local art school, he ensured part of the remit of his responsibilities was the promotion of video art amongst his students. As he began to engage in collaborative video projects with the school members, “Video Earth Tokyo” emerged, undertaking over a period of a decade a series of avant-garde experiments in the seemingly personal media of video and its possibilities of collective expression, often screening their works on a local cable TV network. Whilst the “Earth” of Video Earth Tokyo does not explicitly refer to an environmentalist position, Nakajima himself has long been concerned with these issues, developing an ecological approach from as early as the 1970s. He has explored the five elements of life “wood, fire, earth, metal and water” through media technology, often combining natural and living forms with technological devices. His videos are frequently overrun by nature, for example in the 1994 “Soul of 12 Trees” filmed at Plaza Gallery, Tokyo, wherein TV monitors are engulfed by trees – and in many cases smashed as plants rise from their electronic depths in a literal take over by nature putting the paltry achievements of humankind into perspective. It of course therefore follows that he is fiercely concerned with the human ravages upon nature brought about by the Fukushima disaster and has been developing various projects in the region, including “Requiem Dance in Fukushima” (2011). Yet we are left to question Clement’s theory here, with doubts as to how nature might migrate to and thrive in the exclusion zone, contaminated and abandoned by human life.

“Under the Bridge” is a simple single-channel video placed modestly in a corner of The Garden Hall entrance, but with this convergence of subject, historical significance and background of its creator, this work is a most apt introduction to the “Garden in Movement” concept and the continued legacy and relevance of media art.

Emma Ota

Emma Ota