The Year in Art 2008 — Part Two

This article follows on from part one, which covered January to June.

July was a good month for architecture exhibitions and shows addressing ecological issues. Gallery GA held “International 2008”, a survey of architectural projects covered during the past year by GA magazine (reviewed by Jessica Niles DeHoff), and Gallery Ma presented “Thinking Drawing, Working Drawing”, a solo exhibition of renowned Australian architect Glenn Murcutt that focussed on the importance of drawing in the formulation of his ideas (reviewed by James Way). Meanwhile, the Misawa Bauhaus Collection’s ongoing program of Bauhaus-related exhibitions featured “BAUHAUS experience, dessau”, which explored the architectural school’s history through the coursework of its former students (reviewed by James Way).

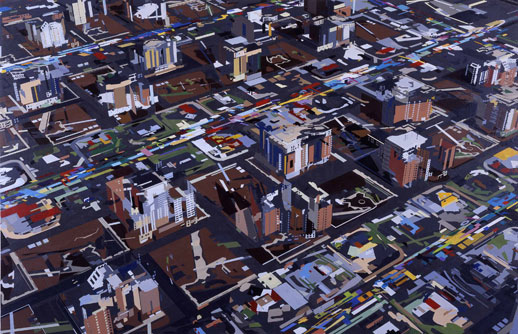

Benjamin Edwards’ solo exhibition “Democracity” revealed a painter’s deconstruction of architecture and the urban environment and was the highlight of this year’s program at Tomio Koyama Gallery (reviewed by Jessica Niles DeHoff). His series of canvases were a whirlwind of layered multicoloured fragments — spirals, whorls, bars, grids, ovals, squares, circles and triangles — evoking windows, doors, fences and road markings and conveying a sense of rushing through infinite permutations of urban space.

Photo: Ikuhiro Watanabe; © Benjamin Edwards; Courtesy Tomio Koyama Gallery

Photo: Ikuhiro Watanabe; © Benjamin Edwards; Courtesy Tomio Koyama GallerySeen from a distance, these fragmented, disintegrating and shifting compositions looked like vector graphics, but a close look would reveal their painterliness: in dark areas the surface of the canvas had the texture of asphalt. While Edwards’ paintings depicted a generic urban environment, they seemed to resound particularly well with Tokyo, not only in terms of the visual confusion, but through composition and technique alone: the elevated perspective was reminiscent of ukiyo-e and seen up close the sharp delineations of masked-off areas of paint were as intricate as locally produced kiri-e (cut-paper works).

Held concurrently at the nearby Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, was “Rooftop Gardens” (reviewed by Andrew Woodman), a large group exhibition of Japanese and Western artists presented in rooms according to various ‘garden’ themes — garden of the grotesque, garden of the night, closed garden, and so on. Adopting a more literally green theme was Fabrice Hyber’s “Seed and Grow” at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art (reviewed by Darryl Jingwen Wee), which saw the museum’s spaces taken over by grassy installations and beehives; Hyber’s works could even be found in plots of earth in the surrounding streets, with vegetables planted a the base of trees down Nishi Gaien Dori. In the commercial gallery circuit, Arataniurano also presented an ecologically minded show titled “THE SUPERCAPACITOR” showcasing new work by Tadasu Takamine that attempted to raise awareness of the global energy crisis through multimedia artworks inspired by electric charge capacitors (reviewed by Yelena Gluzman).

Another back street, another gallery building

July also saw a major development in gallery infrastructure. Having vacated its well-known and highly convenient premises just off Omotesando last summer, Tokyo’s sorely missed premier art and design bookstore NADiff finally opened its new building, NADiff A/P/A/R/T down a totally nondescript side alley to a back street in Ebisu (see photo report).

Commonly known as the Ebisu gallery complex, the building also houses Magical Artroom (now with more than twice the space it had in its former Roppongi premises), the newly established photography space G/P Gallery, run by editor Shigeo Goto, and Art Jam Contemporary, which handles work by young female Japanese artists. The complex is also crowned on its fourth floor with Magic Room, a restaurant and bar.

A testament to NADiff’s huge fan base, the opening attracted well over a thousand people, and was without a doubt one of the most significant events of the year. However, this needle is hidden in far too large a haystack. Whereas the Omotesando premises always had at least a dozen or so people in it, many of whom were likely to have discovered it by chance as they passed by on an already popular commercial back street, the chances of this new building being discovered by passers by are far too low; even for those in the know, the building is inconveniently detached from the main areas of interest in Ebisu. Every time I have visited since its opening, I have found the bookshop and other venues in the premises nearly empty.

Political highs and lows

August is usually a dead month for the art world, with commercial galleries closed and many museums staging unadventurous thematic displays of works from their collections, but there happened to be a handful of stimulating shows.

“Into the Atomic Sunshine: Post-War Art Under Japanese Peace Constitution Article 9” (reviewed by Darryl Jingwen Wee) at Daikanyama Hillside Forum presented twelve Japanese and international artists’ responses to the issues of war, peace, national sovereignty and collective humanity brought up by Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, which renounces all belligerency of the Japanese state but also affirms its right to maintain land, sea and air forces. One of the most impressive pieces was Yasumasa Morimura’s eight-minute HD video work A Requiem: MISHIMA 1970.11.25 – 2006.4.6 (2006), in which the artist reenacts the most infamous moment of author and playwright Yukio Mishima’s life and career, a politically charged last stand made in the name of Japan’s honour1. Dressed identically to Mishima and mimicking his urgent rhetoric, Morimura has turned the speech into a rallying cry for Japanese contemporary art: “You are artists, aren’t you? If you are, why is it that you are so enthralled with forms of expression that deny who you are?” he shouts. “I can see that not one of you will rise up in the cause of art. With this my faith in art is at an end. All I can do is shout ‘Banzai!’”

In Japan, it is uncommon to see exhibitions or any other form of media outlet address the sensitive issues that surround the emperor and Japan’s actions during World War II, as they are liable to stir up painful memories for the elder generations and deal a blow to widespread national pride. Although “Into the Atomic Sunshine” was a very small show that could only scratch the surface of such vast and sensitive topics, curator Shinya Watanabe should be commended for bucking the general trend for safe, apolitical exhibitions and daring to raise these questions.

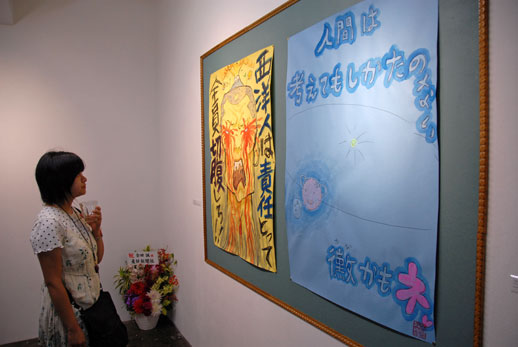

Around the corner at Mizuma Art Gallery, Makoto Aida was holding “I’m Mizuma’s Iwaki!”, his first solo show in three years (see photo report). It was a panoply of controversial imagery in the first room alone: looming large to the right was Moko Moko (2008), a vivid orange oil painting of a billowing mushroom cloud with a cute, hamster-like face on it; to the left was Critique of Critique of Judgment, a wall-mounted work composed of 574 framed pages from the Japanese translation of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment, each with childish felt pen scribbles on them, often reminiscent of sketches by Picasso and other Modernists; and at the back, a painting of a young, naked female quadruple amputee on a leash, hair blowing in the wind and a carefree expression on her face as she cavorts around on her bandaged stumps.

As if these images weren’t enough to tell you Aida is unafraid of getting his hands dirty with controversial imagery, the second room featured an sickly yellow painting on paper of an angry Japanese man with blood spurting from his eyes, Mt Fuji erupting out of his head, and above him, dark, scrawled Japanese characters that read “All you Westerners, take responsibility and commit harakiri!!”2

Aida’s puerile approach to serious issues can grate, but in Japan he is nearly unrivaled in his heavily ironic critiques of authority and convention. Nevertheless, while individual works in this exhibition could be appreciated on their own terms, the show as a whole felt incoherent: it was something of an agent provocateur’s pick ‘n’ mix of half-formed ideas, although this is perhaps an inevitability given that Aida feels little compulsion to present his work as a commercially appealing package. However, incoherence coupled with complacency are not fertile ground for an exhibition, even if not meant to be slick. The gallery’s admission in its press release that “two months before the exhibition was to be held, Aida had not yet formed a concrete plan for the show” and such last-minute planning was to be mitigated by the chance that, like the cocky baseball player Iwaki in Shinji Mizushima’s manga work Dokaben, Aida might pull off an “off-field homerun” at the last minute, left me feeling the show was strike one for the artist and his gallery.

At Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, “Trace Elements: spirit and memory in Japanese and Australian photomedia” (review and curator interview by Olivier Krischer) was an engaging, albeit sombre investigation of “photo media as a memory creation device”. Whereas family photo albums are an edited compilation of happy and funny moments, this show dwelled on more serious considerations of how we forge our reality through the camera and video lens. Geneviève Grieves’ video works Picturing the Old People (2005) exposed the artifice of posed photographic portraits and their subsequent use as historical documents, which Lieko Shiga’s series ‘Lilly’ (2005), ‘Damien Court’ (2004) and Jacques saw me tomorrow morning’ (2003) were presented as constructed memories or dreams based on tentative initial contact with other residents of the south and east London housing estates where she lived (artist interview here).

At the rowdier end of the contemporary art spectrum were Chim↑Pom, a recurring presence throughout the year, who held a solo show titled “Becoming Friend, Eating Each Other or Falling Down Together” at Hiromi Yoshii, in which they imprisoned one of their team in a roughly 3 x 2 x 2 metre hut constructed of concrete blocks for the entire three-week duration of the exhibition. Through a two-way mirror, viewers were able to watch Toshinori Mizuno live with a rat and a crow recaptured from a crow trap in Yoyogi Park3, subsisting only on water and food collected from refuse in Shibuya, delivered to him through a small hole by his colleagues. The crow, reportedly already injured, died not long after the show started, prompting the other Chim↑Pom members to cook it and feed it to Mizuno. In comparison to these actions, the work of street artists looks tame. After four years of travelling around the world, the “Beautiful Losers” exhibition of street artists associated with Aaron Rose’s Alleged Gallery in New York opened at La Foret Museum Harajuku, showcasing black and white photographs of American youth by Ed Templeton, a wooden hut installation of message boards by Stephen Powers and live tattoos offered by Alexis Ross (reviewed by Cameron McKean).

Mirrors and gore: Yokohama Triennale 2008

In mid-September, the two-and-a-half month Yokohama Triennale opened at multiple locations across Tokyo’s neighbouring portside city of Yokohama. Bringing together 72 artists from 25 countries (14 of them from Japan), the triennale took “Time Crevasse” as its theme and focussed on the body, largely through performance work.

As is to be expected of such a broad range of work exhibited under such a loose theme, the show was a hit-and-miss affair. To focus on such a transient media as performance was a bold move for the Yokohama Triennale: when the format of such events tends to be limited to artists and curators flying in, setting up tangible work and flying out, what would be a more ambitious deviation from the norm than to stage transient performances throughout the event? Unfortunately, however, the majority of them were held over the opening weekend only, so few visitors were able to see them first hand. Thus, for many the experience of the triennale was of wandering from room to room, treated only to documentary videos or the debris left over from performances held on site. When the triennale could have been a celebration of the immediacy of physicality in the present, it was instead an ambiguous glance at absence and the immateriality of past actions. At times, “Time Crevasse” could be interpreted less as a theme and more as a disclaimer.

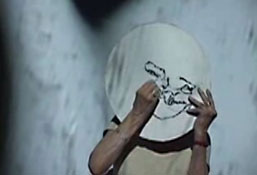

That said, the flip side of the triennale’s lack of explanatory text and the vagueness of its theme was that its best work was permitted to speak for itself. Multimedia artist Miranda July’s The Hallway (2008), installed in the first corridor of the Red Brick Warehouse, literally did so, guiding viewers through a narrow white corridor in which evocative narrative of their journey were spelled out on alternating panels at head height. At Shinko Pier, British artist Ceryth Wyn Evans and British musicians Throbbing Gristle’s collaborative piece A-P-P-A-R-I-T-I-O-N (2008) (reviewed by Rachel Carvosso) was an alluring and serene hanging installation that fused the visual and tactile smoothness of mirror and steel with the intangible aural texture of intermittent beeps, scratches and hums. The dank-smelling, bare concrete storage spaces of BankART NYK — a welcome alternative to the temporary white cubes created for Shinko Pier — had a number of memorable works on display, including a video of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (2003), a Parisian restaging of the 1965 performance at New York’s Carnegie Hall in which members of the audience got up on stage to cut away pieces of Ono’s dress — a poignant study of physical vulnerability and the boundary between the self and others. BankART was also host to an unholy trinity of ooze and gore: Matthew Barney’s Guardian of the Veil (2007) (reviewed by Lena Oishi), Paul and Damon McCarthy’s Caribbean Pirates Pirate Party/Houseboat Party (2001-05), and Hermann Nitsch’s videos of his “Theater of Orgies” mass performance pieces (In September TABlog published a video interview with the artist’s assistant Andreas Stasta at the Yokohama Triennale, but scenes of gore featured in it have led to the video being blocked by YouTube—we will try to find an alternative host). Between them, these works explored notions varying from occult ritual to orgiastic debauchery and social breakdown, and although presented as videos and not live performances, their sheer viscerality jumped out of the screen and put the human body back at the centre of the triennale.

A couple of Tokyo’s key galleries staged solo shows of artists who were taking part in the triennale, such as Yamamoto Gendai, with its display of Hermann Nitsch’s blood paintings and videos of past actions and Wako Works of Art, with “Drawings and Videos” by legendary performance artist Joan Jonas. The other most notable solo exhibition of September was Chim↑Pom’s “Oh My God! A Miami Beach Feeling” at Mujin-to Production. There, they showed a video work from a recent trip to Indonesia that showed Ellie dropping a K-mart plastic bag from a helicopter as she flew over a rubbish field in Bali. The bag drifted down to earth, where it was immediately picked up by an Indonesian worker. Chim↑Pom bought it back from them at a premium price and it was displayed in a Perspex box atop a plinth at Mujin-to Production next to a (sanitized) relief made of rubbish taken from the field.

October began with Tokyo Art Beat’s 4th anniversary party, celebrated in style at Super Deluxe in Roppongi. This year was another busy one for TAB, which oversaw the launch of weekly TAB Talks, the Tokyo Art Map, a new line of limited edition TAB T-shirts, an API that led to innovative developments of TAB data such as the Bubble Machine, and of course, New York Art Beat, TAB’s new sister site in the Big Apple.

Nearby, held in and around the new Akasaka Sacas commercial development was the main art event of the autumn other than the Yokohama Triennale, the “Akasaka Art Flower”, which displayed the work of 18 artists and artist groups in locations ranging from a former kindergarten building, the wooden building of a former restaurant open from 1950 to 1980, and a Shinto shrine.

Shimazaki, the former restaurant, was all paper screen walls, wooden floors and tatami mats. The highlight of the works shown here was Totchka’s Pika Pika (2007), a playful time-lapse video of lightwand drawings that is well-known to the young art and design scene and well deserving of exposure to a wider audience.

Paramodel, known for their winding installations of ‘plarail’ blue plastic rail tracks, was the main act at the former kindergarten building. Much of the contemporary art seen in Tokyo’s galleries and museums art characterized by an unimaginative infantilism, but Tsuyoshi Ozawa’s installation of a mound of futons that visitors could clamber over at the centre of a gym hall and paste their own drawings onto the gym walls — presented together with Paramodel’s paramodelic graffiti (2008), which consisted of plastic rail tracks and polystyrene landscapes snaking all the way up the walls and over the ceiling — was a delightful example of how artwork can retain an infantile character and yet retain a meaningful, playful interactivity for parents and children rather than exist merely as an excuse for adults to engage in self-indulgent regression.

![Photo: Mayumi Sudo Yayoi Kusama, 'Dots Obsession (Night)' ['Dots Obsession (Day)' visible in the background] at Akasaka Art Flower](http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/yia2008_kusama.jpg)

79-year old Yayoi Kusama was exhibiting Dots Obsession, one of her signature rooms of yellow balloons festooned with black polka dots, but its installation here was a severe disappointment. Kusama’s dot installations succeed when they have been realised as all-encompassing worlds in themselves, punctuated by taut, fully inflated balloons that appear both dreamlike and sinister, as if carrying an ambiguous intent. At Akasaka Art Flower, however, dotted mounds that were supposed to look as though they were swelling out of the ground were not even flush with the floor and the balloons hung limply, lost in a space that had too high a ceiling. These potent, compelling symbols of Kusama’s neuroses and mental illness had been reduced to a token display, intended as a crowd pleaser but so poorly installed that first time viewers of Kusama’s work must have wondered what she ever did to earn a place in art history. One wonders if the artist had even been present for the work’s installation. If she was not, then shame on the organizers for failing to honour her work; if she was, then it begs the question: have her standards slipped? Is she now just going through the motions?

Yoko Ono, on the other hand, showed that reiterations of old ideas do not necessarily have to result in staleness. Inspired by a ritual commonly seen at Shinto shrines in which people draw out omikuji paper slips with fortunes written on them and tie unfavourable ones to tree branches to let the wind blow the bad fortune away, Ono’s Wish Tree for Peace (1996/2008) invites people to write their wish on a strip of card and tie it to the tree; the wishes are periodically collected and sent to the artist.

For Akasaka Art Flower, Ono had installed a Wish Tree in Akasaka Hikawa Shrine, underneath a 400 year-old ginkgo tree, the trunk of which still bears the wounds of Second World War bombing. Whereas in the white cubes of museums where Wish Tree for Peace has been shown over the past decade it has stood static, here the wishes actually blew in the wind. Of all the art works featured in Akasaka Art Flower, this one corresponded best with its setting.

October also saw two museum shows that showcased the work of key female Japanese photographers. At the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, “On Your Body” brought together six young Japanese artists and presented their work in terms of the human body (reviewed by Olivier Krischer). Meanwhile at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tomoko Yoneda held a mid-career retrospective titled “An End is a Beginning”, which explored notions of collective amnesia by presenting large prints of seemingly neutral settings that turn out to be historically significant locations, such as Sword Beach in Normandy, where the D-Day landings took place (reviewed by Lena Oishi).

Battle of the Tokyo art fairs set to continue in 2009

In November, following months of uncertainty, 101Tokyo 2009 was officially announced. The second edition of the fair is being directed by Jason Jenkins, with Haruka Ito of Magical Artroom as creative director, but retains co-founders Julia Barnes and Kosuke Fujitaka as advisor and Communications Manager respectively. Although no longer being held at the former high school, its 2009 premises at Akiba Square, where it can accommodate more galleries than before, will keep it in the Akihabara area.

Shortly after this announcement was made, Art Fair Tokyo released the details of its 2009 edition, which is to include TOKIA, an annex dedicated to 29 young contemporary galleries — 19 from Japan and 10 from abroad. Due to the late announcement of 101Tokyo 2009, most of the Japanese galleries that had participated in 101Tokyo 2008 had already applied to AFT and obtained a space in their new annex. Art Fair Tokyo’s official (and ultimately plausible) line is that the creation of an annex had already been planned for some time so as to accommodate prior excess applications. Nevertheless, there remains the suspicion that TOKIA is a deliberate maneuvre to undercut the relative success of its upstart rival.

It will be interesting to see how April 2009 plays out and how sales figures compare: 101Tokyo, which this year exhibited an equal number of Japanese and international galleries, has little choice but to become a predominantly international fair. In the longer term, it will be even more interesting to see whether any Japanese galleries that moved to AFT in 2009 will jump back to 101Tokyo in 2010.

These developments took place against the backdrop of Tokyo Design Week (reviewed by Rebecca Milner), a high profile, well-funded series of major and minor events held in Tokyo’s most glamorous shopping areas of Aoyama and Roppongi, such as the Good Design Exhibition (reviewed by Jessica Niles DeHoff). The sight of shoppers all over Tokyo carrying TDW carrier bags served as a reminder that Tokyo’s visual arts are still heavily dominated by craft and design, and that Tokyo Art Week still has a long way to go if it is to stamp contemporary art on the popular imagination.

November also witnessed the recreation of Nobuo Sekine’s Phase — Mother Earth, first created in Kobe in 1968, and recreated in Tamagawa for its 40th anniversary (see photo report). Phase — Mother Earth is a historically significant work that was pivotal in the early development of the Mono-ha artist group that defined Japanese art history in the late 1960s and early 1970s with their enigmatic juxtapositions of man-made and natural materials.

One of the bigger exhibitions this month was “Neotropicalia — When Lives become Form”, a group show of 27 Brazilian artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. For me, the stand out artist in the exhibition was Helio Oiticica, whose work brought other senses into the art viewing experience, such as hearing, touch and even the most unlikely of senses to be employed in an exhibition: taste — a walk through his installation of radios mounted on shelves in bare plywood and coloured perspex corridors ends with a museum attendant giving you a glass of mango juice.

Solo exhibitions of note in November included “Challenges: Faithful to the Basis”, a compact retrospective of Tadao Ando’s career at Gallery Ma (reviewed by Darryl Jingwen Wee); the odd contrast of slimy grey oil paintings and slick video work by Michael Borremans in “Earthlight Room” at Gallery Koyanagi (reviewed by Rachel Carvosso); the astounding detail of Manabu Ikeda’s pen and ink drawing of a Lord of the Rings-like fantasy landscape of crashing earth at Mizuma Art Gallery; and Keiichi Tanaami’s gaudy graphic paintings in “Colorful” at Nanzuka Underground.

Hello India, Farewell Tokyo

The most high profile exhibition to see us out of 2008 is without a doubt “Chalo! A New Era for Indian Contemporary Art” at the Mori Art Museum. More than 100 works by 27 artists from the subcontinent are on show, highlights of which include NS Harsha’s chairs, placed intermittently throughout the show, their backs extending up the wall into a variety of forms, and the regrettably timely display of Mumbai-based artist Jitish Kallat’s Autosaurus Tripous a sculpture of a three-wheeled taxi rickshaw made of bones that was inspired by the 1993 terrorist attack by Hindu extremists in Mumbai.

At Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, photographer Mika Ninagawa’s “Earthly Flowers, Heavenly Colors” (reviewed by Gary McLeod) was the typically vivid affair one would expect of a retrospective of her work. Aside from the anthropomorphism of her ‘Liquid Dreams’ series of photographs and videos of bright red goldfish swimming together in deep blue water — their seemingly sad and confused faces pulling unexpectedly at my heartstrings — I was bored. Ninagawa is a Japanese David LaChapelle of sorts: all candy coloured sweetness and yet unlike LaChapelle there is no sexiness or wit. The exhibition’s final corridor of purikura style portraits of women came across as an unironic package of non-threatening femininity that reinforces the ubiquitous messages of advertising, that the only way women can and should appeal to men is by being cute, servile and utterly vapid.

© Mika Ninagawa; Photo: Keizo Kioku

© Mika Ninagawa; Photo: Keizo KiokuVivid but not vapid, however, were Peter McDonald’s quirky paintings and prints, shown in a solo exhibition titled“New Paintings” at Gallery Side 2. The Tokyo-born half-Japanese/British painter, who resides in the UK and won the John Moore’s Painting Prize in September, depicts figures with overblown balloon-like heads of transparent colour wandering through everyday settings, many of which are humourous, and yet some also harbour a sense of unease and indefinable menace.

This month has brought with it a few goodbyes. At Taka Ishii Gallery, Daido Moriyama’s “Bye-Bye Polaroid” was a fond farewell to the medium. In February this year, Polaroid announced that they are discontinuing the manufacture of its instant film to focus on digital cameras; their remaining stock is estimated to last only until 2009. Well presented as a continuous line of little acrylic boxes around the room, the images were striking for being of a very high level of clarity not typically associated with the medium. Nevertheless, in light of the success with his retrospective at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography earlier this year, these new works did not come across as particularly important photographs for the artist, and came across as a bit of a whimsical indulgence.

Worryingly, the global economic downturn has claimed its first victim in the Tokyo art world: PingMag. Launched a little earlier than Tokyo Art Beat in mid 2004 and dubbed the magazine “About Design and Making Things”, PingMag has been a bilingual fountain of enthusiasm for visual culture in Tokyo and Japan. With long-term Tokyo resident and design writer Jean Snow having taken over as editor only a month ago, his expertise was likely to give PingMag a greater depth of insight that I was looking forward to, so it is very sad to see the site will be taking an “extended hiatus” and will not be updated “for the foreseeable future”. One glimmer of hope is that Max Hodges of White Rabbit Press is in discussion with Risa Partners, the organization that owns PingMag, about taking over the site. However, at this moment its future remains in the balance.

The final farewell is from me. After two years of editing TABlog, I am handing over the reins to two highly competent editors, William Andrews and Katrina Grigg-Saito. It has been a source of great pleasure and pride to be a part of Tokyo Art Beat and to work with such a dedicated team of volunteer writers and video editors, who have given so much of their time and put so much effort into making TABlog a diverse source of reviews, interviews and features about the Tokyo art scene. I am looking forward to watching Will and Katrina take the site in new, exciting directions in 2009.

Following three and a half years in Tokyo, I am moving to New York City, where I will join the editorial team at ArtAsiaPacific magazine. I still plan to keep my eye on the Tokyo art scene, and I will continue to update the Art Space Tokyo blog as a source of news and links relating to contemporary art in Tokyo.

I leave you with this: a year and a half of TABlog condensed into a couple of minutes (best seen in full screen high definition on YouTube). A couple of weeks after Tokyo Art Beat relaunched with a new design in July 2007, I started to take a screenshot every time the a new article was published with a view to making this video of the changing face of the site. Enjoy.

—

1 In 1970, Mishima and four students of his self-organized army, the “Society of the Shield”, stormed the Tokyo headquarters of the Ground Self Defense Forces, took its commanding General hostage, and forced him to summon together a crowd of officers and men in the courtyard below. From the balcony above the thousand-strong crowd, Mishima decried the government’s lack of strength, and urged the revision of the constitution and a coup d’état. The plan failed, however, and within the hour he slashed his stomach open with a samurai sword and had his aide behead him in a ritual seppuku suicide that shocked the nation.

2 The English title of the work is written “西洋人は責任とって、全員腹切りしろ!” “All Westerners should commit hara-kiri to take their responsibilities!” but the wording in Japanese is stronger — roughly as I have translated above.

3 Since his election in 1999, Tokyo’s Governor Shintaro Ishihara has been waging war on the city’s crow population, now estimated in the tens of thousands — perhaps even over 100,000. Special patrols have been set up to destroy nests, traps have been placed around the city and the birds are no longer afforded legal protection. Suggesting that Tokyo residents even eat their way out of the problem, Ishihara has been reported to say “I hear crow-meat pie is tasty”.

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings