The Sounds of Silence – An Interview with Jaume Plensa

The title “Silent Voices” seems somewhat paradoxical. Can you explain?

I have always been working with words. My main theory is that they are constantly around us. We use words as an extension of our bodies, to expand our thoughts and ideas to the external world. So the body is a very noisy organism. The title “Silent Voices” comes from the idea that what we feel is silent is actually not. Our bodies are constantly creating noise – like a perpetual voice in conversation. But it creates this voice in a silent attitude.

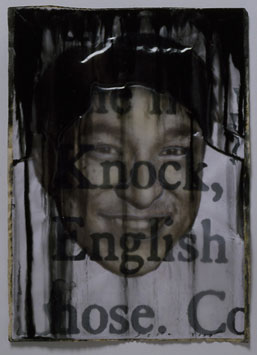

The exhibition features stone bodies covered in text, sitting on the ground. Is the text flowing out from the body itself? Or perhaps it has been placed on the surface from an external force?

The sculptures in this exhibition have lists inscribed on them – the craters of Venus, parts of the body, and so on. These are metaphors for the concept that life is permanently tattooing our bodies. Every second, every moment, our experiences are tattooed on our skin. But the ink is transparent. And then, suddenly you may encounter somebody who can read it and will give you feedback.

I chose to list the names of the craters of Venus on one of the sculptures because Venus is associated with sensuality and erotic ideas, and I have always liked this planet. The craters of Venus all have female names, while the mountains are named after male divinities.

This sensuality or eroticism is not visually evident though; many of the sculptures look the same at first glance.

The sculptures are all self-portraits. The meaning of the tattoos inscribed on your skin are never clear. I like this idea of a strange kind of silence, where you get all this information from a single vessel. Although they may look the same, the meaning of each sculpture is totally different. The visitors of this exhibition should spend a little time reaching beyond the surface appearance and search for the meanings.

The bodies are sitting in fetal positions. Are they being protective, resisting the external world?

No. They are expressing an attitude of looking or facing ‘inside’. Many of my works pursue this idea that people should face their interior selves rather than the external world. We firstly have to understand what is happening within ourselves in order to conceive the universal. The fetal position – the position that we take inside our mother’s womb – expresses this idea most evidently. This is not a form of resistance. Rather, the position allows us to be more pliant to our interior selves. And if we look deep enough, we eventually touch upon a collective memory, or the memory of others. We are all part of one general memory. I think that people will feel comfort in my work because in expressing myself, I am also talking about them.

Apart from self-portraits, I like to also create ‘anonymous’ self-portraits. I feel that when you see portraits, they conjure up associations or memories of somebody else. For example, you may associate an old man that you see with your own grandfather, or a kid with your son. These strangers’ portraits act as mirrors; however, instead of reflecting your own image, they reflect an image of another. This is a metaphor for the globality or universality that runs through my work. You are an example of your community.

Is there a difference in your approach to the large public works that you create, compared to these smaller artworks shown at galleries?

The works at these exhibitions are made for myself, and for the gallery space. In contrast, you need a completely different attitude when creating works for public spaces because they are site-specific. I try to penetrate that context and adapt it to my work; in other words, I try to create a fusion between my interests and the interests of the site. Artworks created in the studio can be more personal. However, with public works, you have to become a mediator between yourself and others.

Your works can be seen in various places around the world, including Daikanyama Address, Hamamatsu, Niigata etc in Japan. Each country or location must have different spatial characteristics. To what extent do you cater to these differences?

It’s true that each location is unique, but I don’t think that humans are so different wherever you are. Japanese people seem to be very respectful in public spaces. Other societies might react differently to certain architectural or spatial structures. But the human desire for beauty, or their wish to transform their everyday life into something more poetic, is the same wherever you are in the world. Fundamentally, we are all the same. I meet and collaborate with many people through working in public spaces around the world, but I always feel that we have more in common than differences.

This is your second exhibition in Japan. What would you like Japanese audience to take from “Silent Voices”?

My previous exhibition also featured this idea of the body, but it focused on its ‘absence’. That was 7 or 8 years ago. The concept this time is very similar: the body as a container for words, for silence, for vibrations. I hope that the visitors will recognize their own portraits through my self-portraits, and that the works will help them to look ‘inside’ in order to understand the world around them. It is a silent exhibition, amidst the noisy era that we are living in today. Hopefully it will help visitors to face their own words and silences, and listen to the noises emitted from their own bodies. It should be a place to think, to be silent, or even just to relax.

Jaume Plensa, thank you very much for your time.

Lena Oishi

Lena Oishi