On the Fence

According to Craig Owens in his essay of 1983 ‘The Discourse of Others’: “if one of the most salient aspects of our post-modern culture is the presence of an insistent feminist voice, theories of postmodernism have tended either to neglect or to repress that voice.” So if something strikes you as quite odd about the seemingly feminist works on display in this exhibition, then you would be right. Titled “Visage”, this all-male artist exhibition groups together works that could be misinterpreted as merely carrying the torch of male subjectivity. However, each of these artists could well be understood as holding their hands up, almost in defeat, and here’s why:

Tomoaki Marubashi would appear fully aware of the fine line he is treading. His photographs usually draw attention to the symbolism of women and his images here depict women playing out scenes in the woods. In one image, women are locked in hand-to-hand combat with other women, each of them prepared to meet their end if necessary. In the other, several women attend to an old gent who is luxuriously sitting and lapping up their attention. My mother used to say that women are better at multi-tasking and these two images would appear to reinforce that belief. Since the advocation of equal rights, women have had to go to war and cook the meals, and to be frank; women are probably better at it. So what is Marubashi saying? Look to the left of the picture of the female entertainers and you will see a woman taking a cigar-break behind a tree while her colleagues keep up appearances. Clearly taking time out from her ‘role’, Maruhashi would appear to employ this image to champion women and admit defeat gracefully, but is he also making a sly caution?

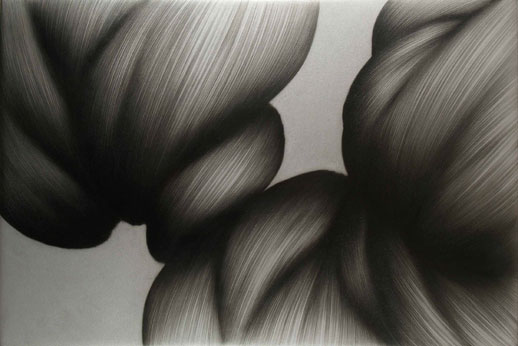

If Marubashi can be said to straddle the fine line then Hideki Sato brings that line to a point and is clear to literally make that line the focal point of his drawings. Japanese women’s hair is said to be the finest in the world, equivalent to that of silk in terms of quality. Sato draws our attention to anonymous heads of hair, meticulously drawn so as to celebrate the beauty of each individual strand. Drawn in pencil on painted acrylic canvases, the effect is almost one of a daguerreotype, such is the amount of lead on the surface, ensuring that one has to be careful where you stand so as to see the drawing at its best. Such attention paid to the angle from which one is to view the works may or may not have been intentional but it certainly reinforces the necessity of looking and admiring, both the examples of hair and the artist’s attention to detail.

Cultural theorists such as Michelle Henning would suggest that we are entering a matriarchal era and that the projects of modernism and post-modernism were patriarchal projects of the pre-digital past. From one point of view, what could be said of all the artists is that they are glorifying the male subjective view of women, playing on ‘prefabricated’ symbolism, therefore conveying a cynical and even fearful view of contemporary society. Yet, they simultaneously display sympathy and to some extent (as in Marubashi’s case) solidarity with a feminist view. The title of the exhibition could be interpreted as “face” or “mask” and thus brings our attention to an age-old argument that still has implications for the future. With this in mind, collectively this exhibition appears to be sitting on the fence, leaving just enough clues to fuel either view.

—

1. Owens, C. cited in Foster, H. ed. (1998) The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Post-Modern Culture, The New Press, New York. pp.65-92

2. Henning, M. cited in Lister, M. ed. (1995) The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, London: Routledge, pp.217-235

Gary McLeod

Gary McLeod