The Man of Many Faces

Opening the doors to Yasumasa Morimura’s two-floor exhibition, I am greeted with the simultaneous cries of Hitler and Lenin. Before I’ve even looked at anything, I’m certain that in his all encompassing “hats off” to the previous century, Morimura has lived up to his reputation for appropriation, and looking back through laughter-tinted glasses.

“A Requiem — Art on top of the battlefield” is a four-chapter culmination of the artist’s “Requiem” series, paying homage and encouraging remembrance, to the events and people that shaped not only him but the twentieth century. His previous work focussed on those artists that impacted him most, but this exhibition goes beyond the boundaries of art history, and engulfs the men and events that have brought about the massive construction and destruction of the modern world.

True to his appropriative heritage, Morimura deconstructs famous news images and portraits and reconstructs them with himself well disguised as the subject(s) (but with his renowned large nose as an omnipresent giveaway), thus bringing these significant events into the modern consciousness. This technique not only serves to bring forth these hugely significant events into twenty-first century minds, but a reminder that, as realist photographer Daido Moriyama suggests, “every photograph is a fake representation of reality”. Not only is every newspaper or television image that reaches us one persons copied and edited version of events, but this copy is subjective, both in the minds of the producer and the receiver.

His first chapter, “Seasons of Passion”, focuses on famous news images. His reconstruction of the 1968 Saigon Massacre taking place outside a Sogo department store drags this history of genocide and Western destruction into twenty-first century Japan. His Chaplinesque reconstruction of the Asanuma stabbing, appears distinctly staged and humorous, a reminder that what we are presented with daily in the news is not a true to life representation of reality.

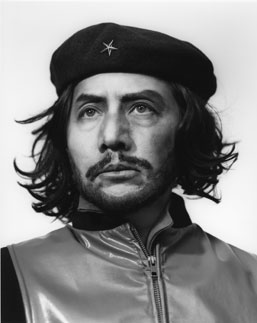

The second chapter, “Twilight of the Turbulent Gods”, sees Morimura dressed as the men who shaped the twentieth century through war, revolution and science. The portraits always depict evidence, such as smudged make up, that this is a costume scene. Morimura is always fun, and this time is no exception. Laughter becomes a vehicle for us to re-read history, and to highlight the pathetic character of these men. From his video reconstruction of Lenin’s 1920 speech (filmed in Osaka) to Hitler lounging on his desk with a plastic globe, Morimura uses humour to highlight the mental corruption of these dictators.

A personal favourite was the direct juxtaposition of Leon Trotsky and Che Guevara: the harsh explosion of light and deep depth of field brings forth connotations of hysterical madness for Trotsky, contrasted with a soft focus portrait of the revolutionary Che.

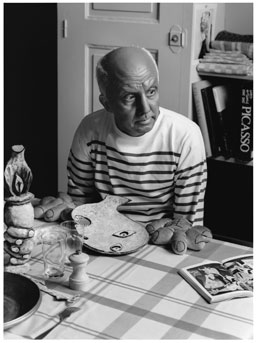

After watching his copy of a copy of Chaplin’s double portrayal of Hitler, head to the second floor and the third chapter of his requiem. This chapter, “Theatre of Creativity”, pays homage to the great artists of the time, with no small nod to Duchamp, instigator of the controversial art movement behind Morimura.

Concluding the exhibition with “1945 — A Flag on the Summit of the Battlefield”, Morimura’s third video installation in the exhibition has a reconstruction of the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, featuring a nameless soldier and Marilyn Monroe. Morimura encourages us to re-evaluate history, with this single depiction of women in the twentieth century. He raises a blank flag, the flag of art, and asks us what colour would we choose? He simultaneously reminds us to remember, reconstruct and re-evaluate, and in doing so progress towards peace, with the final representation of himself as Ghandi.

As may be expected from a summary of the twentieth century, it is pretty heavy-going, and a lot of information to take in first time round. But Morimura succeeds in his homage to the geniuses and dictators of the century, to the photograph as a medium, and to the ordinary people affected by the events of the previous century. It is indeed a requiem.

Amy Fox

Amy Fox