The Imagery of Troubled Sleep

He transforms construction sites into nests, boats and zoos; he equips a flying chicken with long range missiles; he takes X-rays of Shibuya’s most famous dog, dissecting the statue into its mechanical parts forming ears, a brain, eyes, nose, tongue and a “shower”. These are the urban fantasies that drift through the world of Oscar Oiwa as he navigates the urban condition in São Paulo, Tokyo and New York.

The exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo focuses on the Brazilian-Japanese artist’s paintings, which have garnered him critical acclaim but also includes work ranging from miniature landscapes to cartoonish sculptures as well as a documentary about the man himself. His paintings are, in a word, fascinating. They manipulate otherwise banal urban settings, rendering them as fantastic visions that often hide social commentary behind a pastoral veil. Each work of art captures the imagination of your child-self even as it challenges your adult ego with sarcastic humor to question the societies humanity has developed.

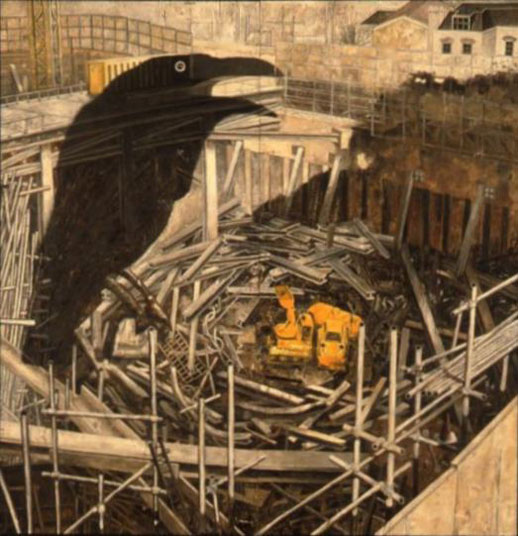

Crow’s Nest (1996) is one I liked in particular for its rearrangement of a skyscraper construction site. Steel beams and poles strewn around the site form the twigs that make up a crow’s nest with an ominous, transparent specter of a crow dominating the frame. In the wake of the earthquake in Sichuan, China, where so many poorly made school buildings collapsed killing hundreds of students at a time, it’s hard not to draw comparisons between the fragility of a bird’s nest to our own structures.

Oiwa’s penchant for helping his audience view the fantastic in the everyday is evident also in Asian Dragon (1995) where a red boat beneath a greenish dock forms the tongue of a dragon. Black tires at the end of the dock become nostrils, a passing freight train forms the dragon’s back, and greenish buildings along the dock form the dragon’s tail. Painted while the artist resided in Tokyo, the piece gives cartoonish form to the booming economies of Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. And yet, the gloomy night, the ominous dirty green and ruinous state the houses that form the dragon seems to criticize these societies for building models of economic success that do not translate into a better life for their poor.

The Hachiko series of ‘X-ray’ paintings of Shibuya’s famous dog are more playful. Five different cutout canvases reveal the dog’s mechanical insides as it shifts through different positions throughout the day while waiting for its master. Close-up paintings of various body parts reveal the screws, bolts, and bindings that make up its organs. Oiwa throws in a little humor with the ‘Shower’, which I’ll leave to your imagination.

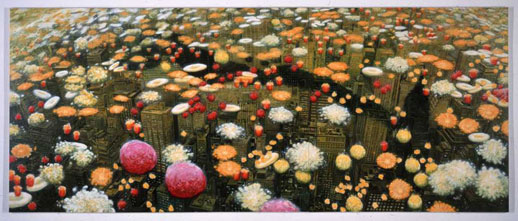

These child-like daydreams contrast with more recent nightmares such as Greenhouse Effect (2001), in which a red-tinted urban landscape conveys the sense of the world baking in an oven. Peace & War (2001) is a two-painting series in which a peaceful, pastoral daytime scene transforms into a hellish graveyard at night. Upon moving to New York in 2002, Oiwa discovered along with the city’s shopping centers, restaurants, and theaters thronging with people, a psychological undercurrent of fear reflected in the dark background of Gardening (Manhattan) (2002). In hindsight, Oiwa appears to have been extremely sensitive to the unease pervading the world early this decade.

The exhibition also displays the draft material — collages of photographs, magazine and newspaper clippings, and sketches — that led to the creation of many of Oiwa’s paintings. What is probably most surprising is the documentary on the second floor in which we meet Oscar Oiwa himself as he works on his paintings in the various studios he has occupied. “He could be an ordinary Japanese salaryman,” commented one viewer sitting next to me. The statement speaks volumes of the stereotypes that inhabit our minds and cloud our ability to view the same world in different ways. But as soon as we feel we are blinded, an artist like Oscar Oiwa comes along to whisk those clouds away.

Ian Chun

Ian Chun