The Hole Through the Microscope

“Holes – Punica Granatum” is the kind of title which implies a little scientific knowledge or at least a curiosity for what this might refer to. Chikako Hasegawa presents work along the lines of fascination and repulsion. If you are tired of one juxtaposition too many (body/mind, concept/craft, self/other) this show will not interest you. Hasegawa writes:

The microscope enables a glimpse of the world of cells which are invisible with our naked eyes. By viewing these pictures and images, we are able to gaze into the inner substance beneath the skin, as if it were of the outer world.

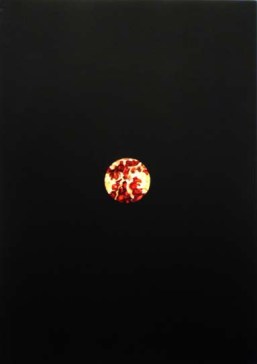

The “holes” in this show are in fact not holes but pictures of holes, illusions of holes. The substance we are gazing at is not a substance but a picture of a substance. The circular shape in the center of ten identically sized canvasses implies some kind of endoscope or medical procedure. Red cells glisten like ikura, and in ‘Punica Granatum 7’ the reds and creamy white makes the whole thing look almost edible. Or are the juicy-looking red seeds a body?

Hasegawa currently lives and works in Tokyo, but was previously based in London in 2002 (as a researcher for the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan) and from 2006 to 2008 (as a fellowship student for the Japanese Government Overseas Study Program for Artists and completing her second Masters at Goldsmiths). Exhibiting since 1995, this show is the first after her return to Japan and her second solo show at the Radi-um Gallery in Asakusabashi/Bakuracho.

Viewing a PR image my expectation was that the paintings would be larger and more graphic, Internet-friendly, fast food consumable. At 42 by 29cm you need to go close to see the detail and you need to spend time looking. Hasegawa makes the most of the small gallery space and its minimal presentation (dimmed lights, small white walls). A matt black surface over nearly all the canvas draws attention to the colorful abstract forms within the central circle. Based on the surface of a pomegranate the abstract colors and textures created suggest internal organs, but without any gore. Instead the textures and hues are delicately executed.

British artist Helen Chadwick has often played with the antagonistic relationship between repulsion and fascination. Unlike Chadwick, Hasegawa’s work does not appear to be focusing on a feminist agenda – there are no specific references to gender, the “bodies” she has created are neutral. The flat nature of the paint does not give us a real sense of the vitality or messiness of body parts, but instead becomes illustrative of a distancing from a real body. These images, if identified with a surgical process or a reduction of the human body to physical matter, could become repulsive, but here they are rendered coldly pretty.

British artist Helen Chadwick has often played with the antagonistic relationship between repulsion and fascination. Unlike Chadwick, Hasegawa’s work does not appear to be focusing on a feminist agenda – there are no specific references to gender, the “bodies” she has created are neutral. The flat nature of the paint does not give us a real sense of the vitality or messiness of body parts, but instead becomes illustrative of a distancing from a real body. These images, if identified with a surgical process or a reduction of the human body to physical matter, could become repulsive, but here they are rendered coldly pretty.

Hasegawa’s main point seems to be that anything can be beautiful; earlier work used poison as its starting point. Creepy, the substance becomes dangerous and seductive, and even though our perceptions may deceive us we want to see. Except that there is nothing new about playing with these kinds of tensions and I can’t help feeling that painting is not the best medium for what she is trying to say. That said, they do look nice.

Her work focuses on the relationship between science, and the ambivalence between its abstract form and our lived experience. We are able to be fascinated with the visual aspects of its beauty because there is no risk. Hasegawa chooses to present us with a recreation of an observation. The introduction of the black border makes us aware of the act of looking. We are prevented from being completely immersed in the experience (if the canvases were larger and just containing color, as in earlier pieces, this would not be the case). Here art becomes visual research and we are presented with some kind of information.

The “observation” however is limited – we are reacting to a reproduction of an experience rather than to a set of information about subject and content. She controls the paint, but any sense of personal involvement has been minimized. We are presented with faceless shapes from unknown sources and are forced to focus on the details. I could speculate on the culture specific nature of a sense of self or engage in a debate about bio ethics. But this would be lengthy and would steer us away from the fact that these works are crafted, and in their painterliness render the viewer helpless but to be anything more than an observer.

Rachel Carvosso

Rachel Carvosso