Takashi Kayama at Toki Art Space

I wasn’t looking for it, which made the encounter all the more meaningful. I’d had a pre-flight COVID test that morning, followed by a curious visit to a major (unnamed) museum of contemporary art in the area and I was on my way somewhere else when I spotted the small basement gallery in Omotesando/Aoyama. Sometimes it’s those occasions when art comes at you sideways, creating not so much an encounter as a sideways brushing past, an unexpected pause, that makes it all the more meaningful. Takashi Kayama’s solo exhibition at Toki Art Space was definitely more about the revelations of gentle journeying than arrival at decisive destinations.

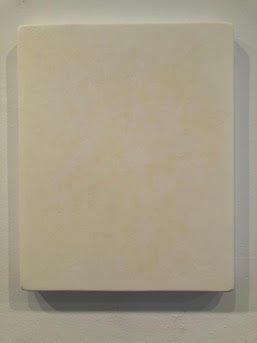

When I say “a room filled with monochrome paintings,” the mind might fly to the power, scale and expansiveness of colour field painting. It wasn’t that – this exhibition was not at all about bravura; rather its delight lay in paintings that were barely there. These works seemed to exist in a state of emergence, a place where painting first lifts itself from a prepared flat surface, a realm of beginnings, of first and tentative markings, of imminent objecthood, when a painting becomes a thing only just separated from the hand of the painter. I am a painter myself and, in full disclosure, my own works engage with this material realm of gesso and ground. It’s the first step in making a painting: a simple recipe for a white chalky liquid soup, often applied thinly and laid down softly, layer by layer. I am drawn to it because the process is meditative and the way clear. Gesso conflates the idea with the material, and that idea is not emptiness or void, but potential. A ground of gesso is quiet and open, ready to absorb whatever happens next. I felt I had found a kindred spirit in this artist, and there he was among his paintings, on the first day of the exhibition. よろしくおねがいします. We met and found that while we could not speak the same language, through painting, we had a mutual language in the space between gesso and before gesture.

At Toki Art Space, Kayama’s suite of paintings were painted on panel and simply titled by date of completion. A minimum requirement for recognition as painting is arguably a gallery lined with rectangular planes. These timber panels, all made by the artist, had softly rounded edges and their surfaces were created by sanding back through layers of paint into the ground beneath, opening up the porosity of the gesso to patterns of chance as remnant paint. I thought of mottled shadows flickering on a wall, marks of weathering or reflections on a pond, a movement from opacity to translucence. Slowly, a colour revealed itself as a gradual retinal adjustment, and only after lingering and looking a while. The monochrome is not the white ground of gesso but yellow. An artist I greatly admire once said to me that the colour yellow is so alluring because it is the colour of joy, but also of madness. Here, I italicise because she spoke in French and that language seems to deepen the saying of it, joy – la joie while la folie softens the edge and suggestion of madness. In the back room, the gallery lighting was perhaps inclined to blue, which in turn seemed to give Takashi’s paintings a very slight cast of dappled greenery.

Dismayed by my lack of communication, I had left the gallery, done the next thing and while I sat in a coffee shop I was able to read more about Takashi Kayama, in translation. I discovered more: Aichi University of the Arts, and a residency in Kassel, Germany. The yellow is aureolin, a cobalt yellow that is warm but also fugitive, meaning it is susceptible to fading and change over time, particularly on exposure to light. The gesso and aureolin are applied one after the other, then sanded back so that the process is at once additive and subtractive. Time is an ingredient; the paintings evolve slowly, over months, even years. His work was once described by a curator as having a ‘depth of stain’ (2) and there is a reference to the death of painting, another bullish narrative, and one which Kayama himself refutes, preferring to see the making of these paintings as healing. In the background to this body of work is Kayama’s other role as a full-time carer for his father and there is a very personal acknowledgement of the bruising cycles of anxiety, nursing, treatment, death, healing and grief as parallels to his disciplined, methodical painting practice. After reading all that, I was moved to return to the gallery, to look once more, to spend more time with these tranquil touchstones.

Takashi Kayama’s exhibition was brief, and closed on May 23, giving me not quite enough time to write this while journeying. The COVID test was negative, and I am now in another country, quarantined and isolated in a neutral room. The memory of encounter with these quiet surfaces remains with me vividly though; the soft edges and how the chalky-white gesso gave way to shifting marks of the warm aureolin hue. The way the artist repeatedly abraded and then healed the ground, and all the things that pattern can stand in for in life. Most rewarding of all, the way spending time with these painting allowed the deep stains to reveal gradually, like slow blooming revelations of joy and despair, coming unforced and unbidden.

(1) Barbara Halnan, b. UK, Australian. Lives and works Sydney.

(2) Takashi Ishizaki (curator of Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art). Source: Toki Art Space website

Lisa Pang

Lisa Pang