Tadashi Kawamata’s “Tokyo in Progress”

This is the twelfth installment in a series of articles produced collaboratively by the Tokyo Culture Creation Project and Tokyo Art Beat. In this piece, TABlog writer Tomoki Sakuta unpacks the “Tokyo in Progress: View from the Sumida River” project led by contemporary artist Tadashi Kawamata, currently unfolding along the banks of the Sumida River.

In addition to conducting workshops, symposiums and talks that seek to reexamine the city of Tokyo, Kawamata has also documented this exploratory process through a series of various projects. For this particular project, he decided to use the area around the Sumida River that the soon-to-be-completed Sky Tree overlooks. The following are just a few thoughts on how this long-term project is unfolding.

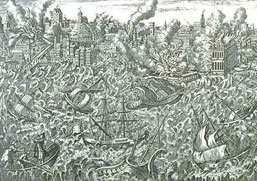

Although the word “ground” is often synonymous with the notion of stability (firm ground, or terra firma), it has sometimes come to be associated with the exact opposite. In a dramatic reversal, this word can also signify a condition of uncertainty and flux, in which a seeming certainty is revealed to be precariously unstable. On November 1, 1755, the Catholic holiday of All Saints’ Day, a massive quake struck the Iberian peninsula, with its epicenter in the Atlantic Ocean southwest of the Cape St. Vincent. The resulting tsunamis and fires that befell nearby Lisbon altered the metaphorical meaning of the word “ground”, and also prompted a shift in the thinking of many contemporary European philosophers whose work would subsequently influence the course of modern European history.

The visible routines of everyday life in Tokyo, nonetheless, have been slowly returning to normal. The city’s residents are gradually getting used to the late trains and various efforts to conserve energy, making their way back to work while grumbling and muttering cynically under their breath. The Tokyo Sky Tree, which had been slowly edging its way towards completion, saw its opening festivities dampened by the generally somber atmosphere of the city, but the tip of the tower still managed to reach its planned height. Yet it is already possible to look upon Tokyo’s “new” tower, soaring straight as an arrow majestically above the city, as an emblem of a past era. We already think of it as a symbol of a quieter, more peaceful time that evokes a certain nostalgia. The Sky Tree has been burdened with an unenviable fate – to exist as a symbol of the disjuncture that separates what happened before and after a catastrophe whose end is not yet in sight. Perhaps it really is a literal symbol of a new Tokyo.

Incidentally, the first time that many Tokyoites caught a real glimpse of the Sky Tree taking shape was probably late last year, after it had encroached onto the landscape of the city’s various neighborhoods. Without any other tall buildings in the vicinity, the lofty heights of the Sky Tree surging up into the air have already become part of the urban scenery. It was as if the tower had suddenly emerged “onstage” from out of the wings and into the air.

“Tokyo in Progress: View from the Sumida River”, the first project in eleven years that Tadashi Kawamata is undertaking in the Japanese capital, centers on the construction of a wooden tower along the banks of the Sumida River, offering visitors a view of the as-yet-incomplete Sky Tree that overlooks it. By inviting participation from children and adults who live in the neighborhood, this project uses the incomplete Sky Tree as a tool for bringing together memories embedded in the local context and connecting them with more recent ones tied to the period of time that will pass before this monument is finally finished.

Currently based in Paris, the globetrotting Kawamata spent a great deal of time investigating different ways of building towers. He traveled around Tokyo in order to get a sense of its contemporary realities during each of his visits to Japan, discussing his proposal with researchers in various fields, artists, architects and the project’s staff members, exchanging thoughts and opinions with them.

For Kawamata, who places much importance on understanding the reality of the site where his project will take place, having meals, drinking and chatting with people are all part of his research. On the other hand, “it would be improper to do anything but maintain an outsider’s perspective on things and try not to intrude too much on the local environment.” According to the artist, Japan isn’t the only place where this standard of behavior applies. The French display much the same attitude: “if you don’t approach the community from the standpoint of an outsider, you run the risk of rejection.”

During the course of his research, Kawamata decided to build his wooden tower in Shioiri Park located in Arakawa Ward, which faces the Sumida River. Workshops for children living in the area given by artists who had joined the project team were held beginning in the fall of last year, allowing the kids to make picture books as well as various objects (miniature towers and sculptures in the shape of their shadow) that would later be displayed inside the finished structure. In addition, Kawamata also launched a new initiative to train and nurture “art constructors” who would be able to work as onsite professionals at other international art festivals abroad. This allowed him to realize an artwork not just at a fixed, predetermined location, but also create opportunities for thinking about the tower project together with local residents and children.

Construction of the wooden Shioiri Tower finally began early this year. A team of builders from Aomori, student volunteers from Tokyo and the newly trained “art constructors” worked together to assemble the structure in no time at all. The topping-out ceremony to celebrate the completion of the tower’s framework was held as planned on February 19, featuring various festivities that took place around the construction site, such as a Japanese wadaiko drum performance and mochi rice-cake pounding and making, organized with the support of the local town association.

In February, just before the topping-out ceremony, Kawamata participated in a series of talks entitled “Dialogues about Tokyo II”, which brought together a host of both Japanese and foreign artists and scholars to discuss various Tokyo-related issues. One of the discussants was video artist Gilles Coudert, an expert on Kawamata’s work who declared Tokyo to be “a place for working and living, a city whose public spaces typically don’t permit you to just ‘be there’. With this project, Kawamata has created for the first time a space that allows people to just gaze blankly at something – a highly symbolic gesture, in my view.”

Although the completion ceremony was slated to be held on March 20, the Great Tohoku-Kanto Earthquake unfortunately struck just before it was scheduled to happen. Both the Sky Tree and Shioiri Tower sustained no damage whatsoever, but the ceremony was canceled. Stripped of its scaffolds and supports, the alluring façade of the wooden tower is now in plain view, and its spiral-shaped passageway has fallen silent as a result of the quake, quietly awaiting the day when it will be able to welcome children inside. For now, however, the tower’s doors remain closed.

Looking back, none of this seemed like it would make a compelling story. What possible relationship could there be between the Sky Tree, a piece of manmade infrastructure intruding upon an urban landscape that changes with the seasons, and a government-led plan to phase out analog transmission in a bid to shift towards a terrestrial digital broadcasting network? I remember the various debates and construction bids that surrounded the matter of whether the Sky Tree ought to be built at all, back when there were still many potential sites available. Once the location had been decided and construction had started, however, the number of opportunities for discussing the subject dwindled (at any rate, whenever the terrestrial digitalization project was mentioned, the thing that came to mind for most people was its deer-like mascot character).

In the last six months or so, the height of the Sky Tree as it gradually grows from day to day has started to become a conversation piece. The process of its actual construction, however, consisted only of a string of short-lived moments that allowed one to actually verify that the tower was taking shape as fragments within a landscape, as well as a set of abstract numbers and figures. For many Tokyo residents, especially people like myself who live on the west side of the Yamanote Line, the inside of the tower as it was under construction had not been opened up for general public view. Neither was there much of an incentive to make a trip to the area just beneath the tower in the name of sightseeing. It was almost as if the Sky Tree could only be felt as a sort of illusory, phantom presence that insinuated itself into the urban scenery, without existing on an official map.

Personally, I see Tadashi Kawamata’s “Tokyo in Progress” as a gradually unfolding experiment that attempted to connect the “ground” of the city of Tokyo with the Sky Tree, a floating presence that seems to be adrift in mid-air, so to speak. Kawamata’s project does not involve a single, definitive narrative. Gazing at this towering structure and being made aware of everything that surrounds us, however, we get a glimpse of the many overlapping stories shored up against it.

Kawamata urges us to not just look upwards as the phantasmal shadow of a massive structure slowly acquires a concrete shape and form, but rather to construct a hypothetical vantage point from which to observe a changing Tokyo. Obviously, because of the recent quake, the “ground” of the city has literally been shaken, and our own bodies, as we gaze at the shifting urban landscape, may also have transformed themselves into something quite different. We would do well to remember that the “ground”, however, also includes the atmosphere and spirit of a place and the lives of its inhabitants. Amid the everyday routines of Tokyo’s residents, who are slowly returning to a semblance of their normal lives while also evolving to become someone different to who they were before the disaster, perhaps the significance of gazing at the Sky Tree — an intermediary presence that straddles the pre- and post-quake eras — and of inscribing that experience into our memory, may evolve and change as well. Seen in this light, Kawamata’s new Tokyo project continues to maintain a particular resonance.

The Shioiri Tower has been open to the public since April 8. Please see the Tokyo in Progress website and blog for the latest updates. (Japanese Only)

Tomoki Sakuta

Interested in architecture and community design as a form of action, and conducts practical, fieldwork-based research on issues pertaining to individual expression through art and information technology, as well as support for socially creative projects.

In 2004, Sakuta founded Arts and Law, a nonprofit organization of lawyers who offer advice and support to artists. Since then, he has been working as its program manager, sharing accurate information with visual artists and craftspeople on legal topics that are rarely understood, such as contract law, ethics and fundraising. In addition to advising legal professionals, artists and others on problems that they encounter in their work, he also organizes talks and workshops that take both theoretical and hands-on approaches to exploring the ethics of publicness. Other articles (Japanese)

Tokyo Culture Creation Project

Tokyo Culture Creation Project