A Summer Night “Delusion” Tour with the Mōsō Cafe

Mōsō Cafe is a walking tour through the backstreets of Yanaka at night, chochin paper lanterns in hand. Each group of up to four people is led by a guide who knows the narrow alleys like the proverbial back of one’s own hand (though a more correct metaphor might be the fine, convoluted lines of the palm). Yes, the chochin are real, illuminated by the slender, white candles often seen at temple altars. They dangle from the end of a stick, like a freshly formed soap bubble.

The forty-five-minute event, which takes place every half-hour Friday and Saturday nights throughout the summer, is a joint project from the local organization Yanaka no Okatte and the broader, citywide Tokyo Art Point Artpoint Project. Rieko Watanabe from Yanaka no Okatte sums up the organization’s intention: “We wanted to bring out the atmosphere [of Yanaka], to pull out the interesting parts.”

Atmosphere is as tricky to define as it is to create. Yanaka, along with Nezu and Sendagi (often grouped together as “Yanesen”) is famous as the part of town that survived, somewhat intact, the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, the fire-bombings of WWII, and the slash and burn modernization of the Sixties and Seventies. It is here, supposedly, that the spirit of the old “shitamachi” (the downtown of old Edo, though the buildings are not that old) can still be felt. The skyline is characteristically low, usually no more than two stories, and there is no neon, not even a flashing sign. Many of the buildings are weathered and wooden; particularly on the main street, there are old-fashioned merchants’ houses, with shops on the first floor. There is also an unusually high concentration of temples — relocated to here from elsewhere around the city during an episode of urban restructuring in the Edo period — and sprawling Yanaka Cemetery, where the last Shogun lies.

These temples and graves, along with the less concrete but certainly palpable spirit of the past, conspire to give Yanaka an eerie, vaguely otherworldly feel. If yurei (ghosts) really do lurk in Tokyo, they would seem to be here, and it is this “atmosphere” that the Mōsō Cafe hopes to throw into relief. “Mōsō”, not easy to translate, can mean “daydream” or “delusion.”

There is also a seasonal element: chochin have long been associated with the summer festival of Obon, when ancestral spirits return to the earthly realm and city dwellers return to their hometowns to receive them. “There used to be a custom of kids walking around the countryside carrying lanterns during Obon,” says Watanabe, noting that for some reason or another the custom seemed to die out about thirty or forty years ago. Younger generations, which include the event organizers, have had no such experience; for many, Mōsō Cafe will be the first opportunity to hold a chochin. The candle-lit lanterns would also seem to have something to say about setsuden (the post-Fukushima need to conserve electricity), though Watanabe says that the idea for Mōsō Cafe predates the earthquake and the timing is purely, though presciently, coincidental.

Kayaba Coffee, a vintage Showa-era coffee shop housed in a building from the 1920s, is the starting point. The cafe was managed by a single family for nearly seventy years until the owner’s death in 2007. A year later, Kayaba was reopened under the joint management of gallery SCAI THE BATHHOUSE (literally around the corner) and the Taito Cultural & Historical Society. Here the past, seen in the original wood-paneled walls, textured glass, brick counter and caramel colored vinyl seats, mixes with the comfortably modern. There are spotlights and a stripped bare concrete floor. A projector plays skateboard videos on one wall. At the counter a stylish thirty-something couple sits at the counter admiring the single drip cups of coffee coaxed from the hands of the young barman.

A tall, slim young man, with a yukata tied at his hips ducks in through the low door. He has a handful of paper lanterns slung over his shoulder. This is Ken Mameta, a Geidai (Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku, or Tokyo University of the Arts) graduate who lives in the area and the guide for tonight’s 7pm tour. He lights a chochin for each of us and leads us into the hot evening (stopping momentarily to furnish our ankles with bug spray).

The tour quickly veers off the main streets onto narrow lanes and then even narrower alleys — the kind of alleys that form odd angles interrupted by crooked stairways. Yanaka (literally “inside the valley”) is just that, inside a valley. It is also a “found” maze. Many of the backstreets are actually corridors that run between the walled graveyards that naturally exist behind the temples. In the half-light, the grave markers, trees, and creeping vines peering over the walls form neat silhouettes. Dusk is the ideal time for the walk to begin, as the light shifts over the course of the walk from blue-gray to black offering the greatest spectrum of imagery.

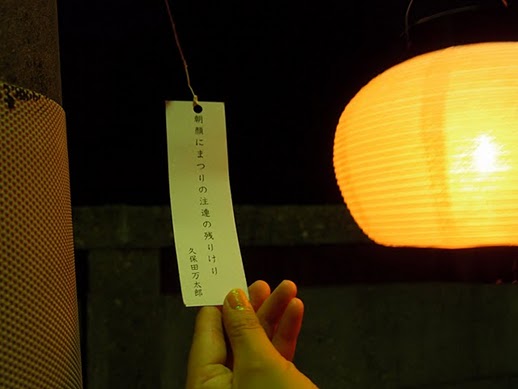

The pace is slow, meandering: the steps of our guide are naturally shortened by his dress, but his path is also non-linear, almost swirling. Leading with his lantern he points out things — minute, mundane and often living things — that line the path at ground level, at eye-level, in between, and over our heads. He brings his lantern up close, for example, to a flower hanging over a fence, close enough to illuminate the tiny ants living inside the petals and waves us over to admire his discovery. The light of the chochin creates only a small sphere of illumination, whatever it lights up on the dark Yanaka streets — lit only intermittently with street lights — is at that moment all one can see; it is like looking at the night through a pinhole camera, with a soft, hazy glow.

Mōsō Cafe is primarily a sensory experience; there are some historical tidbits thrown out, but they are casual, second-hand remarks. This is not a tour in a walk, stop, and listen sort of way. Rather it is more like a guided promenade, or perhaps an introductory lesson in the art of the flaneur.

I won’t spoil the ending.

Mōsō Cafe is not a one-off event, but rather it is part of Yanaka no Okatte’s Guru Guru Ya→Mi→ Project, covered here last year. Yanaka no Okatte is in turn part of a movement that began in the 1980s to keep Yanaka alive, authentic and relevant (though Yanaka no Okatte itself is only three years old). In the past three decades, progressive steps have been taken by several organizations (some are still in existence, others have run their course) in Yanaka to protect old, historic buildings and to encourage a sense of community. The neighborhood’s proximity to Geidai naturally brings art students to Yanaka; many of them choose to live and set up their studios here. There are galleries and events too that have been established in the last twenty years that have shored up Yanaka’s artistic image: the neighborhood’s most prominent gallery, SCAI THE BATHHOUSE, opened its doors in 1993 and the annual art-Link Ueno Yanaka event has been running since 1997. Along with the galleries, studios, and artisan shops there are an increasing number of cafes, restaurants, and bars.

Take the Kayaba Coffee for example: while the streets may be dark and quiet on a Saturday night there is not an empty seat to be had inside. Yanaka has for some time been recommended in guidebooks, both domestic and foreign, as an ideal neighborhood for a stroll or to “get lost in.” This scene — this cachet — however, is something different; it is what has generally eluded the east side of Tokyo, despite its scattered art clusters (Kiyosumi, Bakurocho). That this neighborhood overshadowed by a cemetery and without a train station to call its own should have it is perhaps the most surreal thing to be discovered.

Yanaka is in fact anything but a ghost town.

For more information about the Mōsō Cafe, please see the official Yanaka no Okatte Guru Guru Ya→Mi→ Project website:

http://okatte.info/guruyami/

Rebecca Milner

Born in San Diego, California in 1980, Rebecca studied modern English, French, and Spanish literature at Stanford University. She now works as a freelance fashion writer and trend scout, as well as doing occasional work as an interpreter, English teacher, and bar hostess. Happily infatuated with the mundane, she relishes making coffee, reading the newspaper, grocery shopping, and riding her bicycle. She is obsessed with all things urban, is an ambitious collector of magazines, makes terrible pottery, prefers graffiti to commissioned sculptures, has an unusual affinity for typefaces, and totally digs performance art. See other writings

Tokyo Culture Creation Project

Tokyo Culture Creation Project