Strange Beauty from Merged Traditions: Goto Urushi Kobo

Naruko is known as a hot spring resort town. The town is also known for producing two different traditional crafts: Naruko lacquerware and Naruko kokeshi dolls. As it is with traditional crafts everywhere in Japan these days, the artisans are getting fewer and fewer each year. But in Naruko, an interesting project is underway. A collaboration between the town’s two traditional crafts via the JAPAN BRAND project called NARUKO is happening in an attempt to give new life to the local industry. We spoke to lacquerware artisan Tsuneo Goto about his work and his participation in the project.

Interview by Takafumi Suzuki. Translation by Claire Tanaka

Firstly, could you tell me a bit about Naruko lacquerware?

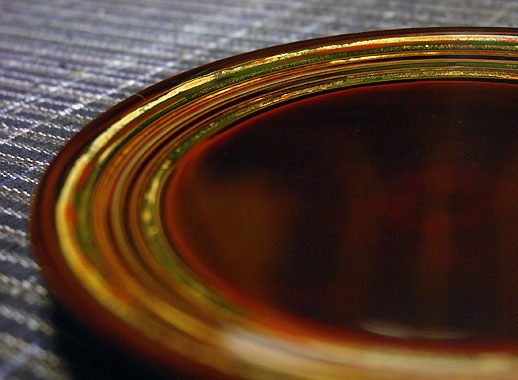

Naruko lacquerware is said to have started approximately 350 years ago, in the 17th century. The feature of the product is how the lacquer is applied in such a way that the wood grain is emphasised. This method of lacquering in a way that brings out the beauty in the wood grain is called kijiro-nuri, and it’s done by repeatedly applying colorless lacquer to the core wood and wiping it off again. This causes the wood grain to stand out, in the fukishiki-nuri style. Clear lacquer applied over red lacquer is called benitame-nuri. A technique that is unique to Naruko lacquerware is ryumon-nuri, which resembles a design made with flowing ink. I personally like kijiro-nuri the best because it makes the wood grain look so beautiful.

There are lacquerware production areas all over Japan, but could you tell me the basic process involved?

In making lacquerware, there is a person who carves the wood core (a kijishi), and another who applies the lacquer (a nurishi). I’ve always been the one to apply the lacquer, so I’m a nurishi. The lacquering process starts out by filling in the unevenness in the wood grain with a type of lacquer called sabi, in a process called sabi-zuke. After the sabi-zuke process is repeated several times, the protruding portions of sabi are sanded down, and the surface is made smoother. After that is the naka-nuri process. The lacquer is applied in a pattern which matches the pattern of the wood grain, and the grain becomes finer and finer. In order to do this, the lacquer is strained through washi paper over ten times. By doing this, the grain of the lacquer gets finer, and the process of coating the piece can begin. Next is the step called naka-togi. This process involves drying the piece while spinning it, and then polishing the surface. These processes of naka-nuri and naka-togi are repeated: coat then dry, coat then dry, over and over. Depending on how many times the naka-nuri and naka-togi processes are repeated, the final result and transparency of the piece changes. Uwa-nuri, applying the finishing coats of lacquer, is the final process. The uwa-nuri process uses even more refined lacquer than the naka-nuri process.

I see. The depth of the black lacquer is attained by a complicated series of processes. Mr. Goto, did you have to undergo an apprenticeship to learn how to do this work?

When I was in my mid-teens, I went to apprentice under a lacquer craftsman in Akita prefecture for several years. When I was in my third year of junior high, my parents took me there and I had a good meal and went to bed in a soft futon and spent the night. And that was it, there was no turning back. I’m the kind of person who does what he’s told, so after I graduated from junior high school, I went there as an apprentice. My training was very hard, and I was young too, and I even ran away once and got on a train bound for Naruko. But halfway home, I stopped at a coffee shop and thought better of it. “I can’t just go home like this,” I thought. And in the end, I stayed for five years learning the tricks of the trade at that workshop.

I see. There you were able to learn the traditions of another lacquerware producing region and bring the techniques back to Naruko.

Yes. I was lucky because they taught me a lot of different lacquerware techniques at that workshop. I know over fifty different styles. Personally, I feel that it’s necessary to lead someone through the basics if you want them to become a proper artisan, rather than the “craftsmen must watch and steal their techniques” method. That’s why if I can find a young person who is serious about learning the craft, I’d like to teach them what I know.

Now, could you tell me a little about your participation in the “NARUKO” JAPAN BRAND project

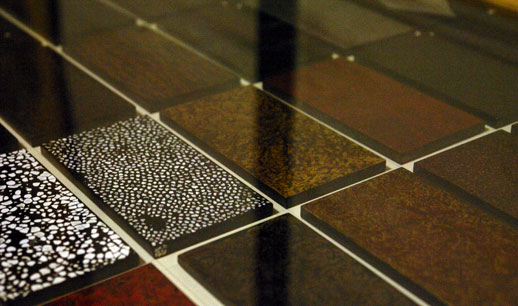

This is a project which combines Naruko’s two traditional crafts, lacquerware and wooden kokeshi dolls, into a series of products which take elements from both crafts. We’ve made objects like candlesticks, coffee tables, and flower vases through the project. Design direction has been done by Professor Masahiko Katsura from the Miyagi University of Education. The woodworkers make the wood cores, the lacquerers do the lacquer, and the kokeshi artisans paint the designs.

Even while you’re based in the same region, it must take real courage to collaborate on something with artisans from a different field.

That’s true. Lacquerware and kokeshi dolls are both traditional crafts with hundreds of years of history. We both have a lot of pride in our work. Lacquerware is something that is used in everyday life, and kokeshi are toys. So, when I was first approached by the Miyagi Prefecture Federation of Societies of Commerce and Industry, my thought was, “Why do we have to work together?” But the numbers of craftsmen in each field are dropping every year, and we figured it was better to do something than do nothing at all. When the project started, there was more of a response than we imagined, and it has become a good catalyst for us.

It would be fun if you could have a worldwide hit or if people began to approach you about succeeding the business.

Well, it’s not as if I haven’t had any interest from young people wanting to carry on the business. Look, I received this letter just recently. It’s from the teacher of a young woman living in Kessennuma, Miyagi. “Please teach her how to make lacquerware,” it says. But when I wonder how motivated these people are, and how much support will be here for new people entering the local traditional craft community, and I realise I can’t take these requests lightly. But I want to try and think things through and tackle this issue in an optimistic way.

A Word from a Regional Project Participant

Support and Guidance Department

Masahiko Higuchi

The NARUKO brand is made of a collaboration between two nationally designated traditional crafts, Naruko lacquer, and traditional Naruko kokeshi dolls. It’s unusual that one town will have two designated traditional crafts like we do. Not only that, but they are both made from wood. This project came from the idea that it would be interesting to try and combine the two local crafts into something new. Professor Masahiko Katsura from the Miyagi University of Education, who handles the design aspect, incorporated a stacking blocks concept to tie the two different crafts together.

In this way, the design allows an infinite number of patterns and combinations. By playing with the wooden materials that both crafts are based on, the products tie in to Japan’s traditional relationship with the natural world and a LOHAS-style (lifestyles of health and sustainability) organic image. By combining the heavy lacquer style with the light touch of kokeshi illustrative styles, a fantastical world is created. We’ve already had exhibitions in Paris and New York, so now it’s time to pursue the next step in our development.

Japan Brand

Japan Brand