The Space Between Two Images

Born in 1977, Jonathan Chandler grew up in one of England’s coastal fishing towns. He is now one of Tokyo’s only foreign comic artists, and probably the only foreigner in Japan to work in the geki-ga style of manga [literally ‘dramatic pictures’, use to denote a more serious and adult form of mana].

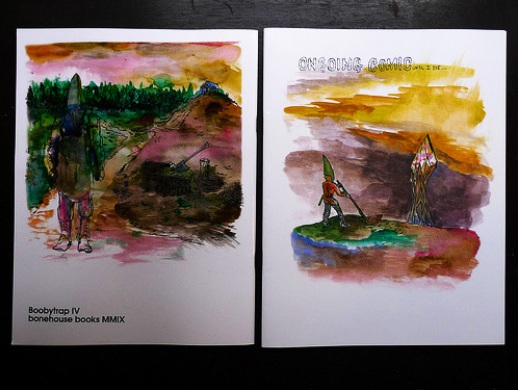

His work is self-initiated, self-learned and self-produced; he has never studied illustration, art or design. Jon has published seven comic books since 2007, including five volumes of the ongoing comic publication Boobytrap, and has also published work by emerging underground comic book artists in the UK. All these have been published through his publishing house Bonehouse Books, which often works in tandem with UK arts collective Famicom. He has been commissioned to produce work for several anthologies (Surgeon White Moss), magazines (Believer Magazine), and most recently the French newsprint Modern Spleen. Jonathan was also the only vendor at Tokyo’s recent art book fair Zine’s Mate exclusively to sell comics.

Despite aesthetic pretensions towards science fiction and fantasy, his stories and images have a surprising humanism which stems the tide of escapism in fantasy comics, often depicting the banal and mundane lives of fantasy characters (replicants, mutants, and mermen). TABlog recently talked with Jonathan on one of Tokyo’s only patches of green grass. In person he is prone to gesticulation, black humour, and speaks rapidly in a thick British accent.

What do you consider it is that you make? Your work doesn’t quite fit into a specific genre, it seems to take the idea of ‘comics’ in a slightly different direction.

When people ask me what I do in Japan I say I am a manga-ka [manga artist], and when they ask what kind of manga I make I usually tell them it’s more like geki-ga. Yoshihiro Tatsumi came up with the term. It signifies comics that are a bit darker, for adults, and not just about entertainment. Basically I just want to use the comic book form for a purpose beyond simple entertainment, in a more free way. Which raises the question: who do I make comics for, myself or other people?

And?

I don’t make them for anybody. I try to make a perfect object.

That’s very idealistic.

I suppose. It goes back to ideas around craft. There are certain rules required for something to be considered a comic: sequential images, things should move, the same characters, and panel borders perhaps. It’s similar to the way you see a movie or a novel. I think there is a craft in putting together a good scene very well. I believe more in crafting a skill or a trade like that.

But you play around a lot with those rules, you don’t even use panel borders.

I don’t. I suddenly realised I didn’t need panel borders, it is a restriction. But what I am making is still a comic. I have developed a style around this which I call ‘floating fantasy’, inspired by ukiyoe, which roughly translates as ‘floating world’. It uses a lot of negative space and you are not bound by rules regarding the stylistic depiction of reality. It also allows me to play with the passage of time that panel borders want to dictate. My latest comic 2×2 uses this style, it wafts in and out of being a ‘comic’. It lets me only depict what needs to be shown; very stripped down, with no unnecessary words or images.

Your story is not only adumbrated, but your content is often very banal. How do you come to that place where these stories seem important? You tend to show the parts between the action: fantasy characters just ‘hanging out’, scavenging, talking with a replication of themselves, or just loitering.

Yeah it is quite banal, but it resonates with people. These ideas just appear, I don’t think about it much. If you mull over your ideas too long you get further and further away from actually realizing them. For me the story gets written as I’m doing it. If I have it planned out it bores me. That’s why I never use pencil, just because I don’t want to draw anything twice. It’s for my own entertainment as well; I want my comics to show the love of drawing.

What do your characters desire?

The men desire woman, but they don’t always get them. What do the women desire though? That’s difficult, isn’t it? My women are pretty cold; some unattainable ideal. In the end my characters just want contentedness.

What makes a successful comic?

Financially not many people are successful from comics. That depressed me as a young man. I was so shocked to find out about someone like Jeffrey Brown. He is quite big, does a lot of books, but still works in a bookshop.

What about in terms of your work, when do you consider your work to be successful or unsuccessful?

One example of something I was happy with is a comic I drew recently for Believer magazine. It is set in L.A. far in the future. A mutant sees a body floating down a river and the comic consists of him pulling the body out of the water and then stealing its armour. He takes all the stuff, lays it out on a cape he ripped off the body, and then he puts over his shoulder it in a bundle and walks off. That’s it. This comic really satisfied me, but I can’t really explain it, or where the satisfaction came from. It reminds me of what David Lynch said: “Sometimes you have ideas, and until you follow them you are not satisfied.” I really agreed with that.

These flashes, or ideas, are like a big rock that has appeared in your head. You have to do something with this rock, you have to get it out somehow, so you begin the process by pushing it down a hill and seeing where it goes.

Jonathan Chandler will be having his first solo show “Floating Fantasy” at Sukiwa Gallery in Nishi Ogikubo from August 14 to 19.

For more information on Bonehouse Books, visit their website.

Cameron McKean

Cameron McKean