Slumping Towards Revolution

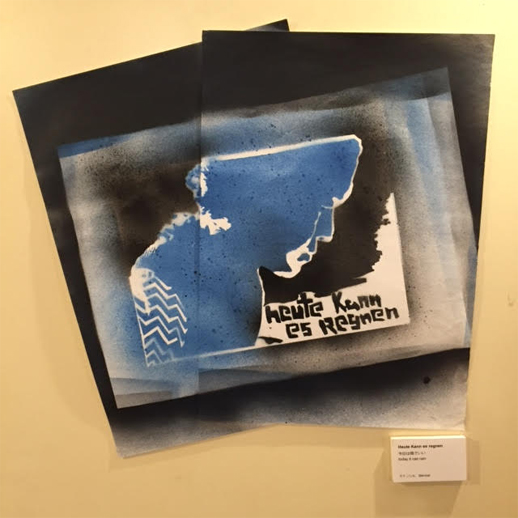

Lukas Martin Hungar is not an expert printmaker, and he uses humble everyday materials such as cheap paper and wood in his work. Still, the self-taught artist and Cologne native, who migrated to Japan decades ago, eloquently articulated his thoughts and feelings in his first solo show, “Nobita’s Exhibition”, which highlighted his body of work stretching back to his early paper stencils. The “Nobita” of the title refers to the artist himself, who was given the nickname by Japanese friends because his languor reminded them of the main character in the popular Japanese anime “Doraemon”.

Prone to lounging about and daydreaming, Hungar’s obvious laziness is in fact a critical response to societal pressures common in Germany, Japan and capitalist societies in general. Yet this lethargy has not prevented him from pursuing his own terms of productivity, which lie outside the norms of society. Whilst he could have chosen a career in a typical job and earnt a stable income, Hungar has instead decided to occupy himself with printmaking and music, eschewing formal training and standard circuits of monetary economy.

As a seasoned DIY artist who dabbles in many fields, particularly punk music and printmaking, Hungar became the founding member of A3BC – an anti-war/anti-nuclear woodblock collective based in Tokyo, known for its astoundingly large-scale woodblock prints and art projects of social critique. Yet his specific method of laziness makes him a distinct printmaker among his peers, who claim even in an exhibition note that if there’s a revolution he must carry out, it must come first from his bed.

This symbolic shiftlessness apparent in Hungar’s creative process is synonymous with the concept of “inoperativity”, or the stopping of machines (living bodies and systems of ideology) proposed by Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben. The relevance of this concept is reflected in the general outlook of the exhibition, which not only expresses social critique but also hints at revolutionary possibilities.

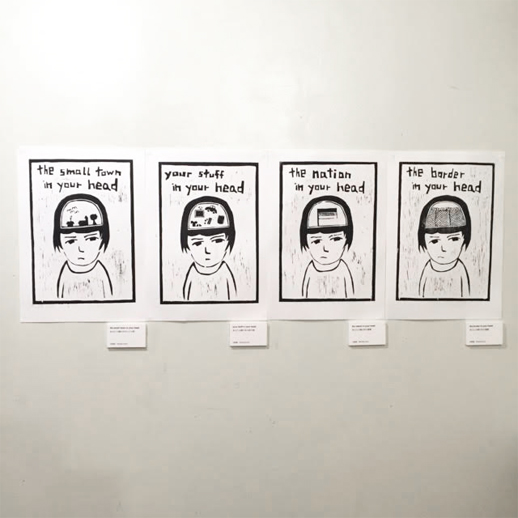

In line with a revolutionary spirit, the work featured offers biting social commentary. The four-piece woodblock print The small town in your head; the stuff in your head; the nation in your head; the border in your head comments politically against growing anti-refugee sentiment amongst some groups in Germany and wider Europe. The stylized figure in the print invokes the satirical approach of German Dadaist George Grosz, without quite-so disheveled facial features. Hungar’s creations are not mere musterings of anger, however; his poetic laziness holds a mirror up to contemporary German society and capitalism in general, suggesting both a refusal to partake in the system and a feeling of impotence within it.

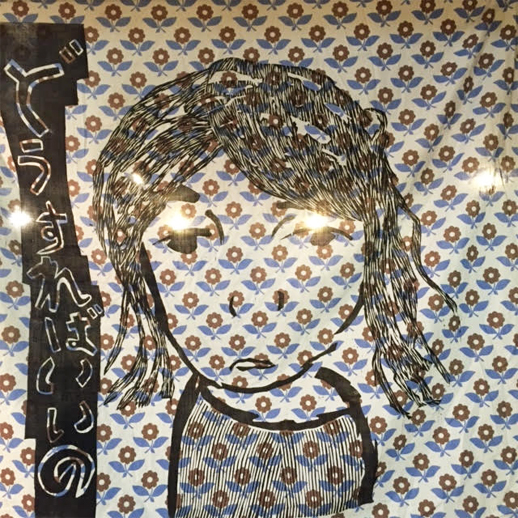

Another woodblock print titled Dousurebaiino? (What should I do?) is a portrait of a young man in an overtly relaxed posture looking inwards, almost daydreaming. The figure is paired with a word in Japanese that expresses uncertainty. The unthinking mix and match of semiotics apparent in Hungar’s printmaking process surprisingly leads us to question the imposed certainty we are expected to accept in our contemporary society.

The figures in Hungar’s prints resemble subconscious self-portraits imbued with the artist’s particular sense of idleness. It is this very element of unemployment or inactivity that allows us to recognize our own limitations and arrive at different possibilities. As the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben puts it, “Other living beings are capable only of their specific potentiality; they can only do this or that. But human beings are the animals who are capable of their own impotentiality. The greatness of human potentiality is measured by the abyss of human impotentiality.” “Nobita” reveals this potential to us by pointing out that we can be whatever we would like, beyond the predetermined occupations that society has imposed upon us.

“Nobita’s Exhibition” was shown at Irregular Rhythm Asylum in Shinjuku, Tokyo from March 6 until March 13, 2016

Jong Pairez

Jong Pairez