Show Me the Pinky Violence

It’s 1972. For the last ten years or so the Japanese film industry has harkened to the signs of decreasing audiences and the rise of TV’s popularity, and has moved toward a more action and flesh-driven commercial model. First with the rise of taiyôzoku (Sun Tribe) films like Crazed Fruit in 1956, then yakuza film’s dominance, going from chivalrous and polished ninkyo-eiga, to hardboiled and realistic jitsuroku-eiga throughout the 1960s, Japanese film-makers responded to low budgets and waning box office sales by doing more with less. Keeping audiences in the theaters lead to films upping the spectacle. Youth film conventions previously were offensive, not to mention illogical, like the rape victim falling for her attacker — that classic chauvinistic male-fantasy beginning in the mid-1950s. Now they develop and evolve, with the 1970s changing the female role to be the active advocate of revenge against family in the Red Peony Gambler series (Fuji Junko), or against rape itself in the Lady Snowblood films.

Increasingly in the 1970s more studios were turning their production toward Roman Porno (Romantic Porno), aka “Pink” films, films that contain regular doses of the flesh. But unlike later hardcore video adult films, these films were soft-core and made to screen in theaters in Cinemascope. They were directed by professionals, and had structured plots and quality images. Often, commercial directors who came of age in the 1970s had no other genre within which to make films, resulting in creativity expressed within the confines of the genre. One vein notable for more abnormal sexuality and exquisite violence are those films made at Toei, known as “Toei Pinky Violence” since their rediscovery in the 1990s.

What can you do within the mandate of budget, of talent, of showing flesh every five minutes? Whatever grabs people’s attention: spurting blood, thrashing fight scenes, sex, seduction and the indomitable femme fatale grace the catalogue of Pink film’s heyday. The 1970s were a time when certain conflicting elements came together: studio quality, talented directors, low-brow content, and the need to pique interest. It gave rise to films that have experienced a comeback in recent years for their ingenuity and uniqueness.

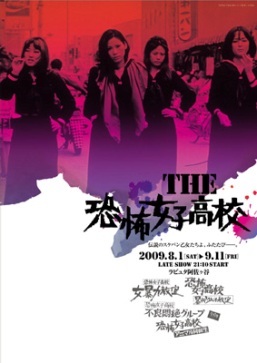

Bringing together the attitude of defiance from Kansai yakuza films and the sailor suit-wearing joshi-kosei (high school girls), this series set in Kobe uses the High School setting to act out revenge and rebellion scenarios where school girls, typically the objects of fantasy or the victims of sexualized violence, take it upon themselves to advocate their place in society and their role as master of their own destiny.

Conceptually an attack leveraged against male patriarchy, these films are nonetheless exploitation films on the surface. Breasts are flung out, crude jokes are told, street brawls and teacher seductions abound. Yet what must be kept in mind is not just the spectacle (however enjoyable or deplorable you find it), but how this kind of ostensibly soft-core cinema is engaged in a dialogue with the lineage of B-film in Japan. The conventionalization of violence and sex in entertainment film has been subverted here — traditional devices of female subjugation become the tools of empowerment.

The first two films in the series are directed by renowned Pink film director Norifumi Suzuki (School of the Holy Beast). At Kobe’s Seikô Gakuen school (seikô being a homophone for ‘purity’ as well as ‘intercourse’) things are out of hand. Girl gangs rule the school and the teachers are happy to just turn a blind eye to the lack of education while proclaiming their school’s motto, “We make refined young women and caring mothers”. The protagonists Miki Sugimoto and Reiko Ike both have suffered injustice that they are trying to remedy through rebellion.

The second film takes a different girls’ school to task; again, agitation between girl gangs provides a catalyst for exposing the corruption of the school’s officials. Replete with scenes showcasing Kobe’s division of industrial bay and affluent hills, concepts of social class are emphasized. This film brings down pretensions of cultural capital in the pedigreed “girls’ school” education through riotous destruction.

In the third film in the series, directed by Suzuki’s disciple Seikô Sugimoto, the girls who rebel are those stigmatized in school by their poverty or mixed-race. In the final installment, the prestigious study abroad program is exposed as a prostitution ring and the girls must avenge the death of their friend.

In Tokyo, subculture is still more marginalized that in America, where ‘subculture’ (music, cinema) has been subsumed into the channels of mass-culture. These films are luckily receiving a DVD release, however much of Japanese 1970s B-cinema is still unavailable on DVD and definitely difficult to view outside of Japan. See these films while you are here or not at all.

Screening at Laputa, Chuo-line Asagaya Station 8/1~9/11

Kenneth Masaki Shima

Kenneth Masaki Shima