Shine a Light

If I threaten to shine a light into your eye, would you look? NTT ICC’s exhibition on the perception of light prompts such a question by initially issuing a warning to those people who may well be sensitive to strobe lighting or suffer from epilepsy. This warning (in addition to being a serious one) helps to play on our curiosity and push us through the door of an exhibition, which arguably needs us more than we need it.

Works such as ‘Printed Eye (Light)’ (1987-2008) by Yukio Fujimoto rely upon us as instigators of our own demise. Here, through the pressing of a button, we are ‘invited’ to expose our eyes to a ‘weak’ strobe light, which causes the residual image of the word “light” to appear on our retinas and stay there until it dissipates. Imagine looking at the sun very briefly through a telescope and you can probably predict the intensity of the experience.

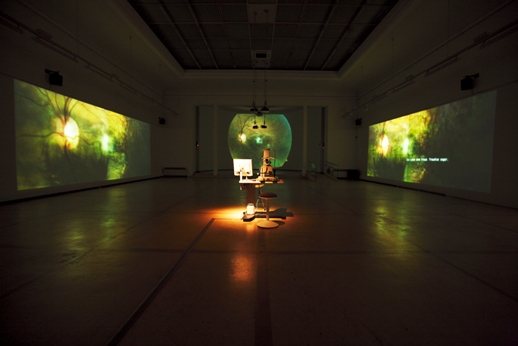

Another work, ‘Thought Projector’ (2007) by the collective Alien Productions, asks us more directly to be involved. Whereas ‘Printed Eye’ played on our personal temptations to push buttons to see what they do, ‘Thought Projector’ asks for our consent. Through the process of taking photographic images of the surface and rear of your eye, streaming them online and juxtaposing them against images from an archive and live comments from internet viewers, we give ourselves over to the technology in order to see the result. Inspired by an unrealized camera that could photograph thoughts, there is a morbid sense of curiosity here akin to looking at oneself through an endoscope. Yet, in this work and ‘Printed Eye’, our participation is necessary.

Ingo Günther’s ‘Thank You-Instrument’ (1995) is another example of participation although it doesn’t ask anything specific of us. Using a strobe light (though this time the work doesn’t involve flashing the light directly into your eye), which etches the visitor’s silhouette temporarily on the gallery wall, viewers are privileged to see their own shadow frozen in real time while they are free to walk around it and play with it. As playful as it is though, this work intentionally encourages thoughts of the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima in 1945, where the flash of the explosion etched victims’ shadows on walls. Spectacular this installation may be (the shouts of sugoi are not to be underestimated here), but this severing from our own shadow – a theme that also underpins Haruki Murakami’s novel (Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World’ – hints at the show’s dependence on us.

A significant handicap of the show is that a majority of the works on display here are arguably more science experiments than works of art, although it does present an interesting opportunity in which to view ourselves and how much we ‘trust’. To experience some of these works properly requires a devoted faith to the sanctuary of the art museum; a ‘safe’ place where an unspoken mutual respect exists between the works and the visitor. No one would expect an artwork to directly harm them despite warnings suggesting otherwise. And some works here even play on that expectation – before flashing a light directly into your eye. However, more often than not, the novelty soon wears off and when it does, thankfully, there are other works here that don’t depend on someone volunteering. A good example would be Jochem Hendrick’s drawings in the middle of the show that do well to literally present the artist’s sight. Drawn by the eye without the use of the artist’s hands, these works allow us to share the artist’s vision without requiring an invitation or instruction. In this way, these drawings achieve what the other works cannot – an enduring experience rather than a novelty.

If Hendrick’s drawings expose the participatory works as frivolous, then the works book-ending the show could be said to poke fun at them. Nam June Paik’s ‘Candle TV’ (1980) and Joseph Beuys’ ‘Capri Battery’ (1985) are intended to hint at the darker aspects of light and our deception by it, but they appear here more as puns. Beuys in particular – suggesting that you can get energy from a lemon due to the light absorbed in making it – would have us think that the rest of the works take themselves a little too seriously. Both Beuys’ and June-Paik’s works are very basic in their construction yet they also achieve what the participatory ones cannot: that any interaction between a work and the visitor should add another layer, rather than merely justify it. Both Beuys and June-Paik are setting a benchmark for artistic integrity. Both knew of something beyond technological frivolity and both knew that when the novelty passes, something more is needed.

Still want to look into the light?

Gary McLeod

Gary McLeod