Fourteen “novels” against the larger narrative. “Seven/Seven: The Fraught Landscape” Review (by Takuma Ishikawa)

Exhibition view

“We need to build history the same way David defeated Goliath”

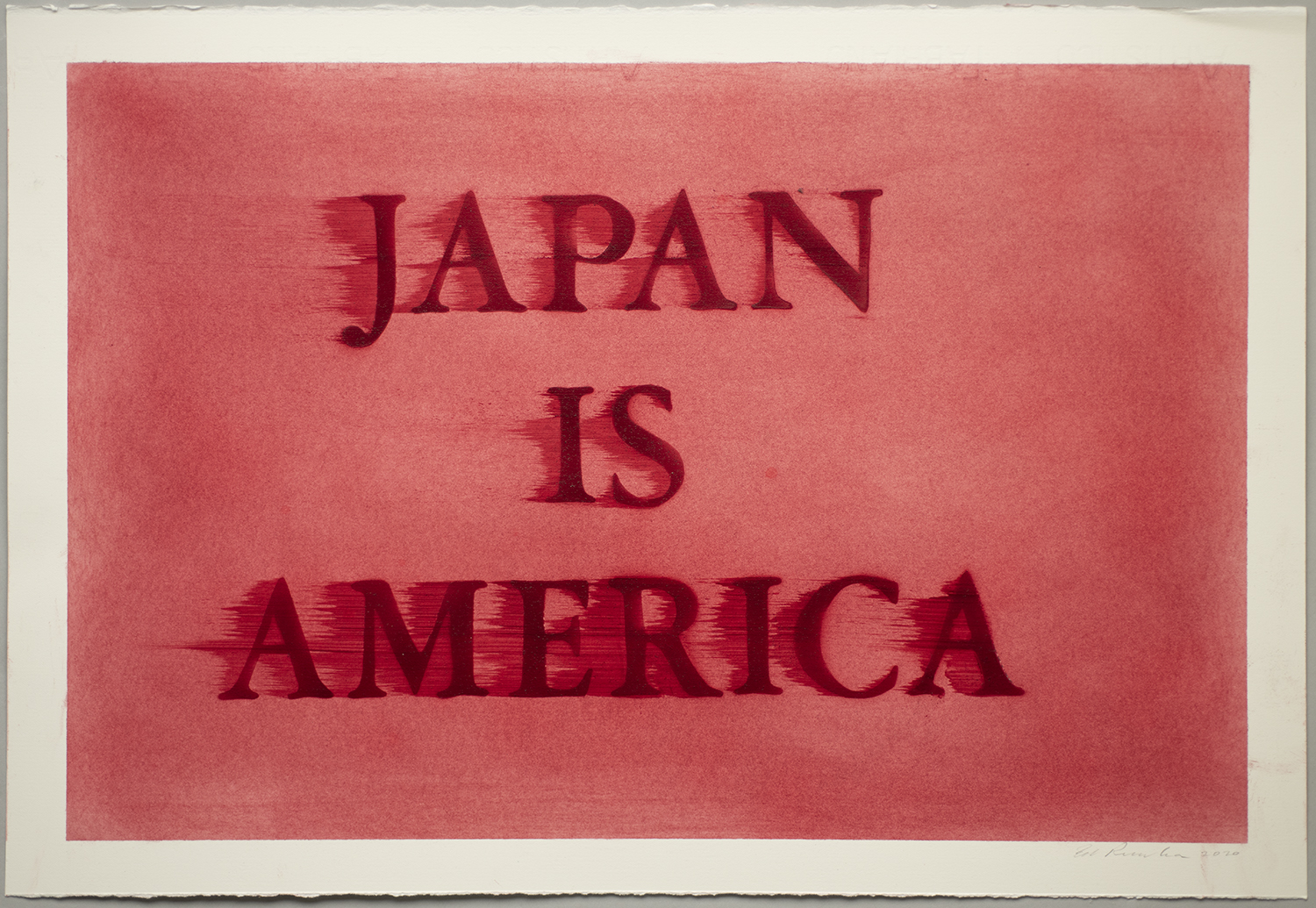

“Seven/Seven: The Fraught Landscape” exhibition at Fergus McCaffrey Tokyo is a conceptual sequel to the “Japan is America” (2019-2020), a group exhibition of 14 Japanese and American artists previously held at Fergus McCaffrey New York. The “Seven/Seven” takes its title from Akira Kurosawa's “Seven Samurai” (1954) and “The Magnificent Seven” (1960), a Western remake directed by John Sturges.

“Japan is America” exhibition demonstrated how Japanese and American artists, active in both countries between 1952 and 1985, maintained an artistic network and communicated with each other. Although the title “Japan is America” sounds shocking, as it implies that Japan is a client state of the United States, the meaning is slightly different since the context comes from a different era. The title is taken from Ed Ruscha's piece “Japan is America” (1985/2019), which is also featured in the “Seven/Seven” exhibition. This piece was a reaction to Japan's mid-1980s bubble economy when its economic presence grew to the point where it almost threatened the West.

While Western influence is essential to Japanese contemporary art (history), the Japanese public has not paid much attention to the influences and relationships foreign artists gained from Japan and Japanese contemporary art. Indeed, the stereotypes of Japonism and anime culture affected and stopped the Japanese people’s imagination. For example, Senga Nengudi, one of today’s most influential African-American artists, was influenced by the Gutai Art Association (especially Sadamasa Motonaga and Atsuko Tanaka) and studied at Waseda University. Anne Truitt, who Clement Greenberg described as a pioneering minimalist artist, worked in Japan from 1964 to 1967, and Paul McCarthy was influenced by Japanese performance art of the 50s and 60s (Gutai Art Association, Yayoi Kusama, Yoko Ono) since his student days. Moreover, the Philadelphia Museum of Art's major retrospective of Jasper Johns, “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” (2021-2022), organized in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, featured a “Japan” section. However, although such cases are not rare, only a few attracted the interest of researchers.

This is not to suggest that we should praise Japan. Instead, I want to encourage people to view the relationship between artistic and cultural influences in a transnational way and develop a global perspective on history that cannot be segregated by country. A micro-network of individuals, a globally constructed “art (history) as infrastructure.”

Japan and the United States are not the only countries where such re-examination and reconstruction of history occur. One of the examples is the “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” exhibition previously held at the Whitney Museum of American Art (2020-21). America was able to break away from the European aesthetic traditions through the cross-border artistic exchanges between American and Mexican artists. Therefore, this exhibition demonstrated the transnational interactions and influences that created the needed cultural foundation for emerging abstract art in postwar America. This is also the “art (history) as infrastructure” to resist Donald Trump's policy of building a wall on the Mexican border.

In Japan, “art (history) as infrastructure” can become the basis for the development of international awareness of international relations in East Asia, human rights issues at immigration facilities, and Japan's response to refugees and foreign workers.

The “Seven/Seven” and “Japan is America” exhibitions share the context of the world history described above. However, they are not identical. The “S/S” exhibition does not aim to demonstrate and advance a reconsideration of contemporary art history in the United States and Japan. Its framework is much more ambiguous, and some works do not share a United States-Japan context. In fact, I found this ambiguity to be a plus. The “S/S” exhibition, which is neither a museum exhibition nor a research paper, does not need to construct an empirical art history. While focusing on diversity, it avoided stereotyping identities such as nationality and race and set up a narrative in which works connected and interacted with each other. By emphasizing the literariness rather than the evidence, the “S/S” exhibition established a connection between writers and pieces from different eras and generations, transcending nationality and race. Literariness is the imperfection (information noise) that adds diversity to the work of art. The subtitle “The Fraught Landscape” served as a literary keyword motif that resonated throughout this exhibition.

Furthermore, the fact that this literariness was composed of small pieces gave the exhibition a political character. The “S/S” may be a small exhibition, but that does not minimize the scale of its concept. Compare this to the world of literature - the greatness of a novel or a poem does not depend on a book’s physical format. Books published by the same publisher are printed on the same paper, regardless of whether they are famous. Could this cause a change in the evaluation of the global works of art and literature? The economic gap is one of the reasons a reconsideration of the “literary effect” is essential in evaluating art. Compare, for example, a Nobel Prize winner in literature with a prominent contemporary artist. Why is it unlikely that an internationally acclaimed novelist such as Belarus-born Svetlana Alexievich would emerge in the world of contemporary art?

I use the term “literary effect” because it implies a connection to the “literary effect” in the visual arts, as criticized by Greenberg, and an impurity that hinders purification and opticality. However, the “literary effect” here is not what Greenberg dismissed as an academism with a sentiment. It should be re-examined in the contemporary art field as something that permeates the entire history of art. As formalism, which sought purification, became a standard and formality, physical formats such as size, materials, techniques, and tools constructed a hierarchy. Later, in postmodernism, the order became even more rigid because it incorporated the premise of capitalist products. One cannot discuss the works of Damien Hirst or Andreas Gursky without mentioning their remarkable physical presence. This capitalist economy of materiality is the most powerful sense and system that holds the central and peripheral hierarchies in place.

We need to unlearn the material value standards and norms developed and expanded by postwar Western contemporary art. For example, we cannot think of the reevaluation of folk art without learning this lesson.

After seeing the “S/S” exhibition, one should not be discouraged by the “poverty” of Japanese contemporary art. Instead, one can sense equivalence, not a gap, between Japan and the United States. Perhaps we can see positive value in this because we are familiar with the sensibility taught and practiced by Instagram and other social media.

Like the publishing method mentioned above, Instagram presents videos and photos in the same format, with everyone sharing works on the same platform. The evaluation and sympathy generated there can be seen as democratization that differs from the material differentiation promoted by contemporary art. Therefore, with the changes brought by the information society, we may be able to re-examine global contemporary art history from the “literary effect.”

Let's look at the works featured in the “Seven/Seven” exhibition. Anna Conway’s painting “Mrs. Lance Cpl. Shane Toole and Mrs. Staff Sgt. Brandon Stevens” (2007) depicts two women working out in a dim room. The title indicates that they are military wives. The body shapes, facial expressions, clothing, and shadows portray the emotional state of two women distancing from society, their loneliness, and their struggle. The social weakness and lost intentions of heroism in this painting are reminiscent of the shadows of American society, well used by Clint Eastwood as a theme for his movies. The small canvas and the “literary effect” are in harmony. The delicacy of this work also resonates with the literariness of Shoji Ueda, who used the Tottori dunes as a setting for his surrealist family photographs.

Setting his work in the wilderness, Joseph Olisaemeka Wilson creates an image that does not divide nature and culture or online and offline. There is a symbolic link between the improvisational sequence of images, the collage-like expression, creation methods, and the camp-like motifs. While many recent emerging African American painters emphasize dense compositions, flawless techniques, and powerful impact on the body, Wilson's work stands out by creating a subtle literariness and a drawing-like lightness and unfinishedness.

Literariness is not limited to representational expression. Abstraction can also have a “literary effect,” and it has become more visible with the help of social media. For example, to show their support for the BLM movement, many responded by posting black squares under the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. Or posted a Mark Rothko’s blue and yellow painting to react to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The “literary effect” in abstraction has been around since the beginning of abstract expression. Re-examining abstract expressionism with symbolism (not cubism) as its starting point leads to seeing abstraction as a “literary effect.”

Another important figure in this exhibition is Richard Nonas, who developed the minimalist vocabulary from his anthropologist perspective. Although his drawings on photographs cannot be described as pure abstract art, their effect is. Five men in the picture are surrounded by red and black; we do not know who they are, what kind of group they are, or what they do. One might speculate that they are not Caucasian but Native American workers in Latin America, but there is no evidence to confirm this. The raw medium of the oil sticks and the gory colors create a sense of violent restraint, giving the finished work an impression that was not captured in the photograph only. It is an abstraction that intervenes in how the subject's identity is seen.

David Hammons' “Orange is the New Black” (2015) also uses color to give traditional African masks a critical perspective. This title is taken from the popular Netflix drama series. Orange refers to the color of prison uniforms, and the idiom “〇〇 is the New Black” indicates the next fashion trend color. “Black” has always been a popular color in the fashion industry. However, here Hammons reinterprets it as “African American,” and in the gesture of applying orange paint to the mask, he critiques the construction of an identity entangled in commercialism.

Cecily Brown follows the tradition of abstract expressionist paintings by Willem de Kooning and others but adds a unique narrative to her works. It is possible to connect her inverted joyful chaos with the erotic chaos of Hiroshi Nakamura's “One-Eyed Girl's Rampage” (1969).

And lastly, I would like to point out that the size of the work does not limit the scale of the content. Tomoko Konoike's “Pendulum Earth Baby Unit 3” (2021) is a suspended small blue sphere in a pendulum motion. This small work created with the simple mechanism seems to hint at the instability of climate change and international politics and remind us of progressing time and gravity. The same could be said of Francesca Gabbianni's animated work “Sea of Fire” (2021), which portrays the coexistence of global change and small individual life and creation.

At the end of the 20th century, we saw the Cold War structure collapse, and history seemed to end. And today, the big narratives are once again returning in a much more powerful form. This is why the little “novels” should transcend the differences of identity and borders and become an interconnected equal network, an infrastructure that can resist excessive violence.