Satoru Aoyama: Embroidering the Traditional and the Contemporary

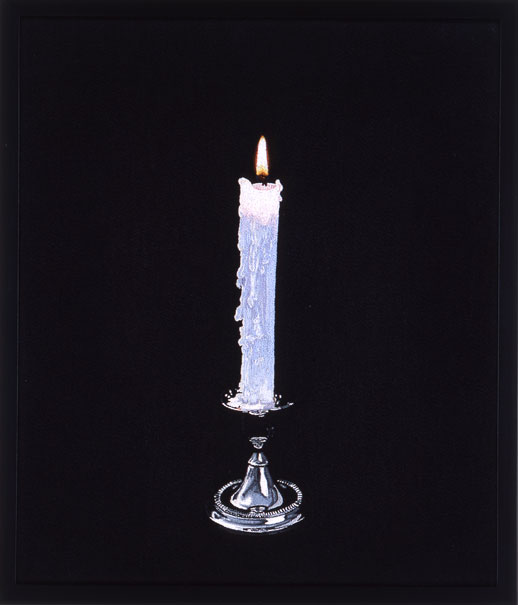

It was early afternoon in April 2007, in a quiet corner of East London under a blissfully blue sky, that I first encountered the works of Satoru Aoyama. Oozing concentrated charm, seven of his recent works such as Candle, Hill and Coffee Stain were modestly hung under the show-title ‘Good Aliens’ on a white wall in a small gallery, ‘One in the Other’, situated beside a canal. At first glance, the works, the largest of which was 130 x 90 cm, were displayed without obvious eccentricity.

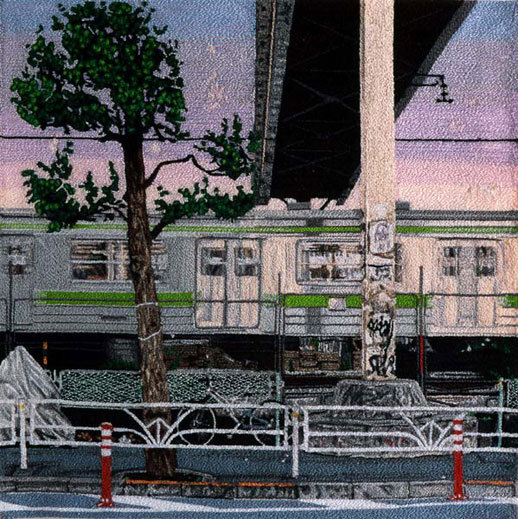

Generally speaking, there is no better means to appreciate a piece of work than in person. Of Aoyama’s work in particular, it’s no exaggeration to say that seeing the original is absolutely essential, as only with the naked eye can you appreciate the astonishing fact that this photo-realistic work, which at first seems to be a traditional oil painting or photograph, is in fact embroidery. There are other contemporary artists using embroidery in their work for outlining motifs or writing letters or text, for example Australian artist Jessica Rankin (whose exhibition at the ‘White Cube’ gallery was held simultaneously with Aoyama’s) and Chinese artist Hu Xiaoyuan (exhibited at Documenta 2007). However, none of these artists go so far as to completely cover their pieces with embroidery, including even the backgrounds, in the way that Aoyama does. In fact, unlike other embroidery artists, he makes every effort to disguise his stitch-work and any evidence that his work is handmade. Once you notice this, you find yourself quickly drawn into his unique world.

Born in Tokyo in 1973, Aoyama completed his BA at Goldsmiths College, London in 1998 and his MA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2002. Over the years, he has developed some highly original ideas and methods. He believes the black of thread is deeper than the black of any pigment and pursues that depth of blackness through the use of embroidery. It seems the understanding of shade, like the analysing of colour, is a significant process for his works. Speaking of colour, he creates his hues not as a result of mixing of pigments, as with painting, but by an assemblage of fine ‘Pointillistic’ stitches, like pixels on a computer monitor. Encountering his work, questions relating to his medium naturally came up for me. I asked him whether he dyes his own thread to get precise colours and about the limitation that embroidery imposes on colour expression. He says, “I haven’t dyed my own thread as there are many shades of ready-made thread available. I do sometimes feel a deficiency of colour gradation in thread but I can usually solve this problem by using different combinations of upper-thread and lower-thread in my sewing machine”. Although Aoyama’s work method to date has consisted of transferring photographs onto organdy and then embroidering over this foundation, he says using photos is just one of the possible methods of creating his kind of works and that he doesn’t intend to persist solely with this from now on.

In the exhibition, Aoyama’s stunning embroidery skills, furthermore his use of a candlestick and a bronze statue – classic oil painting subjects – as motifs, disguised the fact that his pieces were entirely constructed by embroidery. In fact, some visitors to the gallery seemed to pay little attention to the works, perhaps because they came to see ‘contemporary’, rather than traditional art. On this subject, Aoyama commented, “I want my work to challenge viewers preconceptions even a little, however this presumes that it appears to be traditional painting. I suppose some people don’t even notice it is embroidery. There are means to address this, such as showing a video illustrating the technique used, but that would be explaining too much. That’s why I exhibited my work in a simple way this time. I expected some people in London would notice it was embroidery as people there are very exposed to art.” Naturally the fact that his combination of motif, style and medium mirrors ‘time-honored’ oil painting is intentional. With this in mind, he feels it is vital for him to pose questions, to himself and others, such as “why embroidery?” and “what is the relationship between the images and the process of making these works?” rather than merely continue to create surprises or fresh visuals for viewers.

Aoyama’s subjects aren’t only classical ones. Everyday landscapes that are mundane and therefore easy to overlook, like Yamanote Line (2003), are also subjects for his embroidery. These images, appearing like single frames from a film, encourage us to envisage what may happen in forthcoming ‘frames’. Aoyama stitches high-speed, high-tech contemporary life with an ordinary sewing machine and these seemingly incompatible elements merge together in a unified whole.

In the past, he has described himself as belonging to a generation of artists aiming to ‘return to tradition’, however I perceive him to be a ‘contemporary artist’. A distinguishing feature of most today’s artists is that they emphasise the creative process as much or at times more than the finished work and Aoyama is constantly concerned with his medium and method. To my enquiry regarding the intersecting of the contemporary and the traditional, he replied, “More and more I feel that an academic understanding of art history and tradition is essential to artists working in this chaotic world. It is dangerous to stubbornly impose one’s values on audiences. In reality, the process of making art and the context in which you are working are the foundation of mature work of art. I’ve been considering the ways in which I can create a ‘contemporary art’ from those two fundamental factors – the process and the context.” Seemingly, he aims to comprehend and digest art tradition and history in order to sublimate it into an ‘integrated contemporary art’.

Since his first solo show, at the Zolla/Lieberman Gallery in Chicago in 2002, he has exhibited widely in the US, UK and Japan, where, since this spring, he resides after living in London for several years. His upcoming show at the Mizuma Art Gallery in Tokyo will be, according to Aoyama, very different from the aforementioned London exhibition. Perhaps it will hold answers to some of the questions his work poses.

Translation: Ai Kikuchi

Editorial Assistance: Anthony Nott

Ai Kikuchi

Ai Kikuchi