Rey Camoy, little-known peripatetic Japanese painter of the human condition

If J. Alfred Prufrock measured out his mediocre life with coffee spoons, perhaps my own meagre existence since coming, rather unexpectedly, to Japan has been measured out with certain exhibitions—especially those of Rey Camoy.

The first was a retrospective on the twentieth anniversary of his death, shown at an art museum on an artificial island in cosmopolitan Kobe, one of the many cities that the nomadic painter called home during his short life. The second was a retrospective on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death, held at the unassuming venue of the Sogo Museum of Art in Yokohama. Somewhat inevitably, the third was a retrospective coinciding with the thirtieth anniversary of Camoy’s death, currently on display at Tokyo Station Gallery through July 20th.

This time the venue feels more appropriate, located in a turret of one of Japan’s most famous Western-style train stations, with original brick walls and all. Camoy’s work is arguably more European than Japanese in style—he falls into the category, unfashionable today, of yōga, literally, “Western painting”—and certainly his worldview is highly universal. Camoy’s paintings feed a guilty pleasure of mine; I’m a sucker for anything that resembles the work of Francis Bacon, the artist with whom I probably first fell in love with when this Home Counties lad stumbled into the Tate Britain one afternoon. With his deep reds and stark portraits, the work of Camoy contains irrefutable parallels to that of Bacon, and this exhibition is a comprehensive introduction to his career.

Born in 1928 in Kanazawa to a newspaper reporter father, Rey Camoy (this is the preferred transliteration of his name, as opposed to the more standard Rei Kamoi) spent his childhood wandering from city to city as his father transferred posts. Inevitably, Camoy too, when he became an artist, was fundamentally peripatetic: he took up residence across South America, Spain, France and even further afield. He ultimately settled in Kobe, but not happily it seems, as he took his own life in 1985 at the age of 57.

Camoy enjoyed a level of modest success and in 1969 received the Yasui Award, often seen as a springboard for emerging artists. His oeuvre, of which over 100 exhibits are featured at Tokyo Station Gallery, can be broadly arranged into three groups: abstract works, especially those dwelling on motifs of churches; portraits, with the frequent appearance of clowns, gamblers and drunks; and self-portraits, which intersect with the former, since Camoy often casts himself in the role of these wretched characters, his image made recognizable by his unruly grey sideburns.

Camoy’s focus on the Lumpenproletariat figures he encountered on his travels in Europe and Latin America retain an archetypal texture, as if drawn from the canon of world literature. These lost souls include dipsomaniacs, disabled soldiers, mothers and sons. These are the same type of people who inhabit the painting that won Camoy the Yasui Award, Time standing still (1968), depicting four swarthy gamblers throwing dice, with what little each character possesses in the material world hanging on the roll of these tiny objects. The portraits revel in the dusty atmosphere of rustic Europe, backward regions forgotten by the forward-looking capitals of London, Paris and Berlin—a far cry from the glamorous society depicted by the pre-war Japanese artists like Léonard Fujita and his associates who gathered in Paris.

Just like Eliot’s Prufrock, there is an element of the absurd amongst his portraits, as well as a trace of sadness: it is the recurring pose that stands out; hunched back, belly out, chest up, face ruffled. It is a cynical posture, the angle of the world-weary, the bemused and know-it-all. But while these veterans may have experience and wisdom, they are nonetheless defeated by delicate objects they encounter before their eyes—a moth, a dice, a balloon. These portraits are often depicted incongruously, cramped into one corner of the canvas with the remaining surface extending in a menacing void of black or dark color. The wretched of the earth always have despair at their back, a sorrow that Camoy not only painted but also lived, his suicide preceded by several attempts.

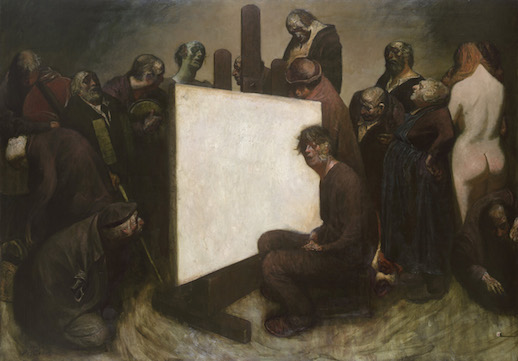

Camoy’s largest and most ambitious painting is Myself, 1982 (1982), which features the artist sitting morose before a blank canvas. Echoing the watercolor Dickens’ Dream by Robert William Buss, all of the artist’s motley band of creations seem to be lurking in the shadows, awaiting embodiment by his brush. It is a meta-painting, the motifs and demons that cannot be laid to rest forever reprising themselves in the artist’s memory.

While the retrospective is organized fairly conventionally by period, a testament to Camoy’s wanderlust that lends itself easily to chronology, the show ends on an oddly muted note after the grandeur of Myself, 1982, with a collection of early sketches of the paintings just encountered. However, the inclusions of Camoy’s actual easel and his final, unfinished painting, along with a photograph showing the painting on the easel in his Kobe atelier at the time of his death, vividly remind us that Camoy died at the height of his talents. Following a time of frustrated experimentation with nudes in Kobe in his later years, at the end of his life Camoy had been returning to his best style of painting.

William Andrews

William Andrews