Questioning and Connecting: Aichi Triennale Artist Interviews

The fourth Aichi Triennale, subtitled “Taming Y/Our Passions,” opened in Nagoya and Toyota in Aichi Prefecture on August 1st. Already making waves with its equal inclusion of women and men artists in the early press releases, this year’s iteration is exceptional in its inclusion of many artists and artworks dealing with a range of social and political issues—including climate change, nuclear war, colonialism, gender identity, and sexual violence—to a scale rarely seen in Japanese institutions. While one section devoted to previously censored art works has since been the target of heated responses, this is but one of many political gestures in the Triennale’s curatorial choices.

The following five interviews with Aichi Triennale artists, conducted on opening day just before the sudden closure of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?’,” hint at the range of critical expressions on show. The artists have diverse approaches to art making, often in collaboration with communities, and also with a common push for questioning and looking again at societal norms and political issues.

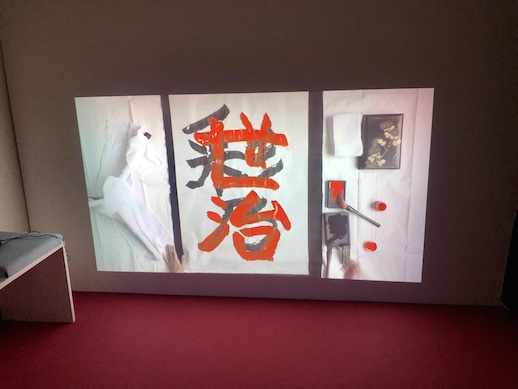

Kyun-Chome

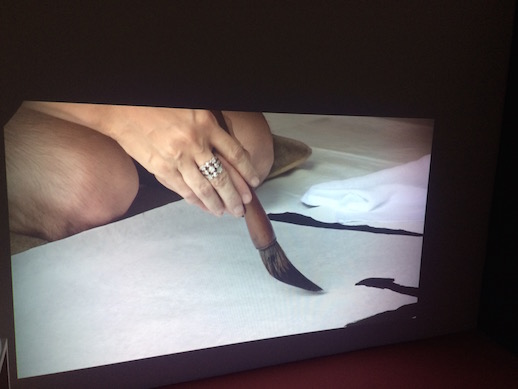

In the video I’m Sage (2019), displayed in a building near Nagoya’s Endoji shopping street, a middle-aged mother and her child perform Japanese calligraphy, a process that requires the teacher to guide the hand of the learner. The mother first guides the hand of Sage, a non-binary person, as they both write Sage’s former name (Ayano). Then, over the first letters, Sage guides their mother’s hand to write in bright red ink her child’s new chosen name.

The video is the product of the socially engaged practice of the artist duo Kyun-Chome (est. 2011), which works closely with communities to create art that will benefit both the artists and their subjects. Members Eri Homma and Nabuchi facilitate valuable experiences for their subjects. They began making works together to artistically respond to the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and ongoing nuclear crisis. One of their earliest projects was collaborating with Fukushima evacuees at their temporary housing outside the evacuation zone. They invited participants to reimagine their towns, now out-of-bounds, by erasing the barriers and danger signs in photo-editing software. “We realised how fun it is to work with people. And by offering a new or unusual experiences to our participants, we could help them learn something more about themselves.”

“Our choice to work with transgender and non-binary people for our Aichi Triennale commission was inspired by the festival’s publicly stated aim to include an equal number of women and men artists, which went viral on the Internet,” said Homma. “It’s an approach that highlights the binary genders. When the Aichi organisers said they’d reached gender equality, I knew that they hadn’t asked every participant the gender they identify with (although later we also heard that Kyun-Chome was not in the gender count because we are a group).”

According to the artists, the video shoot was the first time Sage had declared their new name to their mother. Sage is resolute in their proclamation, at one stage saying, “You should trust me when I make decisions about myself.” By focusing on names, Kyun-Chome was also responding to the “passion” referred to in the festival’s subtitle, “Taming Y/Our Passion.” For Homma, “Choosing a name for one’s child is a way for parents to transfer their hopes and dreams and love to the child. So for transgender and non-binary people to change their name, that is a powerful act that will impact the parents. The act generates another strong amount of passion.”

Nabuchi shared that he had met Sage about ten years ago. Throughout the years, Sage changed their body and started identifying as non-binary. “Sage decided to come out to their family as we began to work on this project with them. Again, the project offered a chance for the participant to do something unusual. With our support, Sage came out to their family and we captured one part of that process in the video.”

Kyun-Chome shared a post-note on August 16 regarding the closure of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?’” (translated from Japanese by the author):

“This incident has certainly visualized and strengthened division in Japan. We try to imagine the motivations and feelings of those who are angry at the content of the closed exhibition. We are aware that Aichi Triennale received a lot of angry—even violent—phone calls and emails. We should try to understand what these people want to protect and what they love, but there is no need to succumb to their threats and demands. There are many divisions in this world, including between left wing and right wing, men and women. But art can make you imagine outside of these binaries. Our Aichi commission proposes such an imagination, and we think the work can encourage less division. We support other artists who do this as well.”

Hikaru Fujii

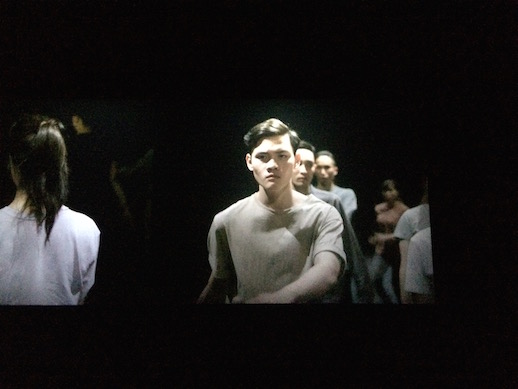

Hikaru Fujii (b. 1976 Tokyo) often connects the uncomfortable elements of 20th century history—specifically Imperial Japanese colonization across Asia—to contemporary society. Through detailed historical research and fieldwork, Fujii facilitates filmed workshops in which participants engage with the results of his exploration. For his Aichi Triennale commission, Fujii responds to archival footage of Japanese-occupied civilian training centres in Taiwan during the Pacific War. The students are physically and verbally drilled on table manners, writing, calisthenics, and bowing to become “Japanised.” The artist has worked with a group of young Asian migrants in Japan to re-enact the gestures captured in the footage. Both the archive film and video of the participants’ choreography are displayed alongside each other as Mujo (The Heartless) (2019) in Nagoya City Art Museum.

Given the sensitive topic of Japan’s Imperial past, Fujii has been no stranger to the concept of censorship in his art practice. Fujii shared, “There have been many times where my works have been censored before they could be displayed. Anywhere in the world, it’s difficult to find a place where freedom of expression is perfectly protected. Especially in Asia, freedom of expression is heavily restricted. Therefore, I think it’s natural to start from the state of mind that freedom of expression can easily be censored. The tension is always there.”

“What I’ve learned from this is that it’s necessary to be careful with the language that I use. Authority is often driven by language. Word choice is important because it’s often by Googling a specific word that people can find what they dislike. It’s certainly not done through the context; nobody really cares about the context. It’s specific words that are picked up in a mechanical data search. Even without the direct language, I trust in the imagination of my audience to interpret the meaning.”

Fujii’s projects often involve group actions and re-enactments captured on video. For the artist, working with groups of people is a means of representing a collective body. “My works are about understanding what happened in the 20th century, and so much of that history has collectivism or group mentality at its core.”

Working with a group also produces a sense of dynamism—collective action appears at once uncontrollable as well as impressively synchronised. “This dynamism is a way to understand 20th century history. Ultimately, I want to understand this history to understand what is going on now.”

Tsubasa Kato

Tsubasa Kato’s (b. 1984 Saitama) approach is also a response to political climates, both in the US and Japan. Throughout his practice, Kato has focused on visual and performative manifestations of struggle and co-operation. Like Kyun-Chome, Kato’s work has been heavily shaped by the 2011 disasters, with works such as Fukugawa, Future, Humanity (2011) operating as a reflection of the crucial role of social co-operation in Tohoku’s recovery.

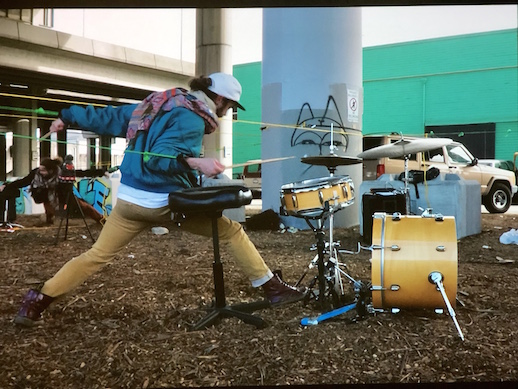

Kato’s two works in Aichi Triennale seem like a departure from this expression of solidarity and sense of achievement; in fact, they could be the very opposite. In Woodstock 2017 (2017), four musicians are tied to each other, impeding their performance of the US national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner. Kato discussed the inspiration behind the work: “While I was living in the U.S., I witnessed the U.S. presidential race of 2016, so I felt as immersed in politics as everyone else in the country. The people in the video were my roommates in Seattle. I got them to play their instruments while tied to each other, so that they became obstacles for one another and they could not all play at once. It’s quite similar to the political and social divisions in the US now.”

Kato has made another constraint act here in Nagoya for the Triennale. Three musicians atop the Oasis 21 building attempt to perform a rendition of Japan’s contentious national anthem, Kimigayo, on traditional Japanese instruments. When discussing this work, Kato first reflected on the Triennale’s subtitle for this year. “In Japanese, it is “jo no jidai”. “Jo” has many interpretations. It can mean information, or a strong feeling, and more. Having a number of possible meanings creates a distance between the reader and the word. In a similar way, there are multiple meanings that come with the Japanese anthem. It has a militaristic association because it was sung during the Pacific War. But Kimigayo’s lyrics are not explicit. It doesn’t have to be about war, and kimi doesn’t have to be addressing the emperor. If bi-racial Japanese people or Japanese people with multiple nationalities perform this anthem, and struggle against the others in dissonance, I think the meaning changes once again.”

Tsubasa Kato provided a post-note on August 15 about the controversial closure of “After Freedom”:

“After this closure and its related discussions, I am feeling an even deeper division between artists and curators, Korea and Japan, right wing and left wing. My two works, in which people are connected by ropes while they struggle to play, seem to speak even more closely to my observation that everyone is connected but without a common direction or goal. I know that the Aichi artists are in solidarity, even though we have taken different strategies to respond to censorship, like withdrawing works or signing petitions. Together, we will show how we can struggle and play in response to this critical situation for freedom of expression in Japan.”

Michiko Tsuda

Within the historical Ito Residence near Nagoya’s Endoji shopping street, Michiko Tsuda’s (b. 1980 Kanagawa) You would have gone there to see them by then (2019) occupies a quiet, tatami-floored guest room. She subtly plays with perception—is that a window, or a mirror? Where is the camera’s reflection?—and suggests parallel timelines, eerie symmetry, and other unexplained elements.

For Tsuda, making her audience question their senses of perception is key. “My installations have three elements: space, performance, and audience. They actually started as just studio sets for filming videos, in which I control the viewpoint of the audience. Installation is a form of expanding the film set. This time, I wanted my audience to stay a long time in the rooms with the video, so I created spaces that can add more to the experience and offer a trigger for viewers to be more sensitive to their surroundings.”

Tsuda prefers site-specific installation outside of regular art spaces. “When working in a non-gallery space, I am really careful about how to use the site, because I feel like the Ito Residence is perfect already. I didn’t want to add more. Instead, I worked with existing elements including the gardens, fusuma screens, the low table. I found a new way to present them and change their use.”

When asked why Tsuda wants to manipulate space and change perceptions, she said, “It’s important to have alternative perspectives. I like using stages and “white cube” galleries, but often they determine a static relationship between artwork and audience, which does not generate creativity. By manipulating these expectations, I can prompt audiences to look again and question what’s actually there. This will lead to critical thought.”

Michiko Tsuda provided a post-note on August 16 about the closure of “After Freedom” and its widespread responses:

By talking and thinking about the tense situation in and around Aichi Trienniale, I think it is bridging some of the distance between art and society. Generally, Japanese society avoids these kinds of confrontations and keeps distance from one another. But art is troubling this status quo, making people confused. I hope it will lead to new answers and a much-needed solidarity.”

Tomotosi

Yuki Tomotoshi, going by Tomotosi (b. 1983 Yamaguchi), makes art works that renegotiate people’s relationship with the city. His commission for Aichi Triennale, Dig Your Dreams (2019), engaged a group of residents of Toyota City. In a video resembling the format for morning television reports from the field, a reporter fronts the camera at an archeological dig. Locals are excavating the discovery-filled layers of earth underneath a shop at Toyotashi Station. They have discovered prehistoric, Jomon-era ceramics with a familiar motif resembling Toyota’s overlapping ellipses logo.

“I thought Toyota City was synonymous with Toyota Motor Corp., Japan’s highest-grossing company, but there are hardly any signs of it in the city center. My project came from asking locals about their relationship to the company and their city in general.” In the artwork (the title is a parody of Toyota’s slogan, ‘Drive Your Dreams’), the company’s relevance to Toyota City’s everyday life now seems to have been buried, like ancient relics.

Tomotosi also has a video performance on display, Japan, the Beautiful, and Ourselves (2019), in which the artist attempts to give English-language instructions to Tokyo commuters over a loudspeaker while wearing an official-looking Tokyo Olympics 2020 uniform. The artist, inspired by Hi-Red Center’s Street Cleaning Event of 1964 and Christoph Schlingensief’s Foreigners Out! (2002), gently encourages the commuters to move along, have a productive day at work, and remember they are representing Japan. Some passers-by passively follow the directions, others briefly look over to him as a curiosity, and many others remain oblivious to his actions. “If relationships are not maintained and metabolised by people, the relationship between cities and residents may make for an unpleasant, cramped life.”

The author wishes to thank the artists and Kanako Tamura for her assistance with interpretation.

Emily Wakeling

Emily Wakeling