Public Art Series #7: Taro Okamoto’s Myth of Tomorrow

Before being unveiled in November 2008, a large public notice on an empty white wall in Shibuya train station announced the imminent arrival of a mural that had long since vanished from modern art’s vast archive. Almost four decades since it was created, twelve years since the artist Taro Okamoto (1911-1996) had passed away and three years since his partner Toshiko – who not only located the lost mural, but orchestrated its recovery from Mexico – also passed away, was it installed posthumously as a prominent public artwork in central Tokyo.

Originally commissioned by Manuel Suarez y Suarez for Hotel de Mexico in Mexico City during the late sixties, Myth of Tomorrow (1969) was also painted there. Unfortunately, the entrepreneur suffered financial difficulties that prevented the ambitious hotel from being realised, and so all fourteen panels of the thirty-metre wide mural went into storage. The details of its whereabouts were mislaid and its location went unknown for thirty years, until Toshiko unearthed it and began arranging for its shipment to Japan.

Depicting the effects of the atomic bomb, Myth of Tomorrow shows a devastating panorama of destruction. Rendered in a semi-abstract modernist style, it recalls the work of other avant-garde artists who portrayed fierce physical conflict. Okamoto’s opus is a memorial that shows the ruin of more abstract forces at work. Ablaze with wild fire and violent contrasts, it’s a memorial that honours soldiers and the residents of Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Visually, it’s comprised of an array of symbols that satellite a skeletal figure with a bent spine and hallow eye cavities. This figure’s scale and position are determined for optimum impact. Its chiaroscuro of bones is so dramatically portrayed that it’s difficult to imagine it having more emphasis. If you view the mural from directly below, you’ll see that the bones curve out from the panels in low-relief. Emblazoned centrally, this figure dominates the composition, adorning it like a pendant. The entire mural wears death as a centrepiece.

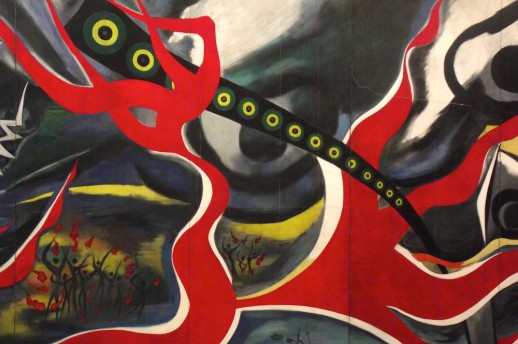

Eyes recur throughout the painting; both as giant smears on the right, as well as on the crimson piranha-like creature on the left. Above this piranha-like creature are five eye masks that diminish as they arch into the distance. Eyes are also suggested on the black banner that threads its way through the flames on the right, with a perforated band of circles within circles that ripple through the work. All these allusions to sight are deliberate, as they, and we, bear witness to the atrocities of war.

So much emanates from the skeletal figure; zigzagged lightning, plumes of smoke and comet tails of fire. There are vibrant streaks, distortions, and surges of volcanic force. While groups of match-stick silhouettes are kindling to the flames that fringe the lower regions, streams of wispy spirits soar above. Despite the horror of his subject, Okamoto’s flair for theatricality lends the mural an exhilarating charge.

As well as the subject itself, another reason for its theatricality could stem from the original cultural context it was produced for. It’s easy to overlook this when you see it at Shibuya Station, but it was initially created for a hotel lobby in Mexico. Although the spectre of death could seem an incongruous subject for a hotel, the imagery used – especially the skeletal figure and eye masks – seems to acknowledge the Mexican festival The Day of the Dead. Had Okamoto chosen the iconography to resonate with these undertones?

In a recent talk at Shoto Junior High School, Masayasu Kobayashi from the Taro Okamoto Memorial Foundation suggested a way to read the mural by separating it into three distinct tenses – past, present and future. In characterising the pictorial chronology by reading it from right to left, he posited that the two main branches of fire to the right hand side are the two nuclear detonations and represent the past. The skeletal figure in the centre serves as a lasting reminder of the fatalities that ensued, representing the present. And finally, on the far left, we see a pastoral cluster of figures that represent a peaceful future. Kobayashi’s explanation unpacks Myth with clarity, where Okamoto’s work is seemingly muddied visually.

Myth of Tomorrow is rightly among the annals of modern art history, but it’s also a work whose story as an art object can eclipse its content. Another difficulty with Okamoto is that his oeuvre is entwined with an enthralling biography that occasionally overshadows what he’s produced. Instead of being a backstory, it can sometimes become the story itself.

It is marvelous that Myth of Tomorrow can be seen freely. The decision to present it outside a national museum, if only as a conservation issue, is astonishing as well. But despite these aspects, its context and content aren’t mismatched. Seeing it within such close proximity to the ultra-modern surroundings of Shibuya crossing helps to situate it within its own epoch.

The fire in the lower section of the Myth of Tomorrow is crisply defined with white outlines, while the background is indistinct. These smeared shapes and organic forms are like shadow play on the walls of a cave, cast by flames flickering across bumpy surfaces. There are the match-stick silhouettes and animals running, just as bison roam the rock face savannahs of prehistoric cave paintings. I can’t help wondering if Okamoto’s mural doesn’t belong to an older, more elemental narrative, if it isn’t primitivism and the magic of fire that he’s really captivated by, as much about creation as it is destruction, made by an artist and a war veteran.

“Art is explosion.” Taro Okamoto.

Nick West

Nick West