Public Art #4: Faret Tachikawa

A five minute walk from Tachikawa station is a thicket of integrated urban narratives that constitute “Faret Tachikawa”, the most extensive public art project of contemporary international art within the wards of Tokyo.

Curated by Fram Kitagawa in 1994, it was conceived as part of an urban regeneration programme during the early nineties that sought to stimulate an urban hub that had previously been home to a decommissioned air base. As an advocate for the “regeneration through art” concept, Kitagawa’s “Faret Tachikawa” preceded both the Echigo-Tsumari Triennials (since 1996) as well as the Setouchi Triennales (since 2010). On how spaces can be transformed, Kitagawa wrote:

“Artists discovered urban functions such as exterior walls, parking ramp walls, lighting, bollards and tree grates, and turned them into artworks, as if birds had looked for places to build a nest”1

Borrowing the Italian verb ‘fare’ meaning to create, the projects name simply added the letter ‘t’ to the end of the word to represent Tachikawa. It boasts an impressive array of global contributors; Vito Acconci, Donald Judd, Rebecca Horn, Anish Kapoor, Martin Kippenberger, Claes Oldenburg and Richard Wilson being among the large number of artists involved. “Faret Tachikawa” has one hundred and nine artworks by ninety-two artists from thirty-six countries, installed in five designated zones.

Despite what must have taken an astonishing amount of co-ordination, the results are often rather quiet, if not covert, creations. Overall, most works are modestly scaled, unimposing in character and unnamed. Deliberately anonymous by design, discovering artworks and distinguishing them as such is left to the resident or visitor to determine. No longer is art the stuff of exalted treasure (although the city’s website does feature a mystery tour), but discovering them becomes an everyday encounter that unfolds on the raised pedestrian walkways and beneath the tracks of the monorail instead.

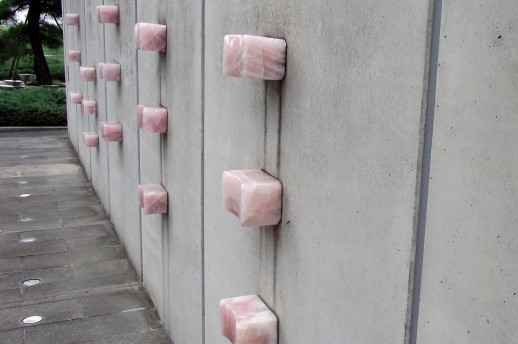

Serbian performance artist Marina Abramovic is an exception to this trend as her work is labelled. Embedded in a bare concrete wall are fifteen powder-pink quartz blocks. Protruding at various heights, they’re aligned vertically in groups of three. A discreetly positioned plaque beside them provides the title, “Black Dragon: For family use” and the following instructions, “Facing the wall, press the body against the rose quartz pillows and wait”.

The pillows themselves are gently concaved to fit the contours of the visitor’s body. Based on the heights of a five-member family, they are positioned to connect with the head, heart and hips. Having found three that fit your body’s proportions, you turn away from the traffic a few feet away and wait. But wait for what? Abramović’s practice often involves a direct relationship with the audience, invariably utilising the body and testing the limits of the mind. With your field of vision limited to the wall your nose is pressed against, it feels as if you’ve turned your back on a firing squad in the street.

Which isn’t to say that all the pieces at “Faret Tachikawa” offer such ominous circumstances, some are simply functional. The late American artist Robert Rauschenberg’s Bicycloid IV (1994) traces the lines of a readymade bicycle with neon tubing. Positioned above an underground bike garage, it operates as a sign. Ordinarily, there are more illuminated lines and curves to be found high up on hotel facades by the Greek artist Stephen Antonakos too. However, since March 2011, the works that require electricity at “Faret Tachikawa” have sadly been unlit as a power saving measure.

Some works achieve privacy, despite their scale and civic context. The late Thai artist Montien Boonma created a work called Rock Bell Garden (1994). Within a secluded garden are two structures beaded together from perforated bronze bells that have weathered a cool green hue, like oxidized copper. The smaller of the two is a metre high conical sculpture with a rock supported in the centre. The larger is an enclosure about four metres tall and consists of two walls that form incomplete cylinders that wrap around one another to enshrine a rock in the centre. Although the bells may be touched, it’s not immediately apparent that access to the garden is permitted, and although they would make a sound; the clappers have been excluded, rendering the bells silent and lending the structure the ambience of a temple. Frequently cited in relation to his Buddhist beliefs, Boonma’s garden seems almost kōan-like, producing as he has an almost unattainable refuge for meditation that is seldom entered.

Other works are easy to miss too. Some are simply too slight to be noticed or are positioned beyond the view of many. Take the late Cuban-born American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ contribution. Prior to “Faret Tachikawa”, one of his most celebrated public artworks was a series of billboards in New York City called Untitled (1991) that depicted the empty bed that he shared with his partner Ross before he died of AIDS. Untitled was a poignant tribute. In Tachikawa, Gonzalez-Torres’ billboard is subtler still. Positioned on an exterior staircase on the side of a cinema complex is the image of a gull soaring toward the centre of the frame. Looking up from the street, what you see is what you would have seen if the building hadn’t been built. It’s a kind of stand-in image, a substitute for an absent view.

These subtleties couldn’t have been exploited as effectively in a central district of Tokyo, where animated advertising and scrolling characters jostle for our attention. But in Tachikawa such commercials are scarce or else located closer to commercial centres. As soon as you notice one artwork, another appears, until you find yourself noticing the subtle qualities that make up the street furniture. The curve of an air vent, the material that cases a lamppost, or the design of a fire hydrant can take on a more pronounced quality once you’ve started looking.

Equally, these neutral urban circumstances allow for less discreet work to stand out too. Probably the most surprising work to stumble across is Sunday Jack Akupan’s Stranger (1994). Right in the centre of “Faret Tachikawa” are fourteen life sized Nigerian tribal leaders. Dressed in vividly coloured and patterned robes, they look out onto a pedestrianized precinct with staffs, horns and dignity. Half of whom are seated; the other half standing, some holding small percussive instruments, but all wearing ceremonial attire. Made from cement before being hand painted, Akupan’s process imitates that of grave art. In this case, describing a distant and deceased clan, leaving us without answers as to which tribe it commemorates or why they have departed.

For the most part, “Faret Tachikawa” isn’t a project that draws enormous attention to itself. The work is well integrated among the fabric of the city, being as easy to live alongside as it is to appreciate leisurely, without imposing itself or contriving an appreciation for contemporary art where there isn’t one. Its unobtrusive character is its success, rewarding those who seek to engage with its narratives or, in the words of the participating American artist Vito Acconci, “[…] art is no longer a noun, it [has] become a verb. Art is nothing but a general attitude of thickening the plot”.

1. Quote from Tachikawa Art Map

Nick West

Nick West