Personal Exploration in a Virtual City

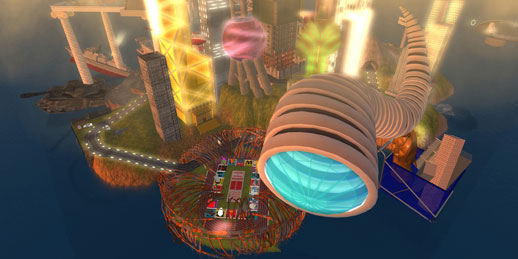

RMB City is literally a work-in-progress; a virtual urban development cum art project, conceived by artist Cao Fei within the massive multiplayer online world called Second Life (SL). Cao’s video and photography works, prominently shown in a string of biennales and international exhibitions over the last eight years or so, have formed the artist’s signature style, appropriating motifs from self-consciously ‘international’ expressions of youth culture, such as hip-hop or cosplay, often set against an incongruous contemporary Chinese setting. Her earlier involvement in the film project San Yuan Li (commissioned for the 50th Venice Biennale), with versatile writer, designer and art activist Ou Ning, also gave Cao a taste for urban research as art. RMB City shares similar aspects of such earlier works, claiming to question what it means to be Chinese, or indeed to be “China”, amidst rapidly developing hybrid urban spaces, in a world increasingly leveled by real-time, trans-national communities mediated by the internet.

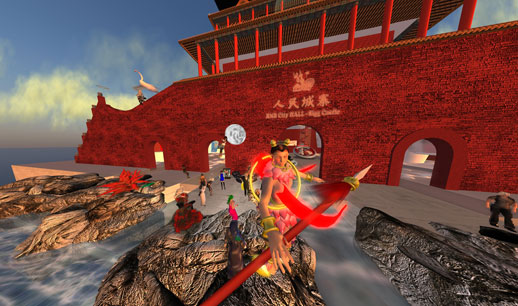

“Live in RMB City” is yet another iteration of the RMB City project, which presents four videos on wall-fixed flat screen televisions, and two large video projections, as well as published materials detailing aspects of the project to date. Captured in the real-time 3D environment, these video works are essentially a form of machinima. The main work, also titled “Live in RMB City” (2009) is a 24-minute video, projected, showing Cao’s Second Life avatar, China Tracy, introducing her new son – China Sun – to RMB City. In reality, Cao has recently become a mother herself. The SL baby China, who speaks in Japanese here (with English subtitles), poses simplistic, pseudo-philosophical questions to China Tracy and other characters from the virtual city, such as the city mayor –- who is in reality Jérôme Sans, director of the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art (UCCA), Beijing. Such questions –- “Where did I come from?” “Can you die in Second Life?” -– may resonate for some with any number of animation or earlier literary references, yet set to kitsch music and by now familiar CG graphics, many will find such musings merely banal or self-indulgent.

The UCCA was one of the first institutions to set up virtual shop in the city, although now they have been joined by the Guggenheim Museum. The fuller development of RMB City appears to have originally been commissioned by the London based Serpentine Gallery1, where Hans Ulrich Obrist, who has closely followed and supported the young artist’s career, is co-director. The entire project, in its various exhibited iterations, lists the extremely influential art collector Uli Sigg as “facilitator”, and RMB City now sports a Sigg Castle. Sigg, the former Swiss ambassador to China in the 1980s, also established China’s first award for local contemporary art, the Chinese Contemporary Art Awards (CCAA), and remains chairman of its board. In Second Life property development costs (and earns) real money, so part of Cao’s work has been a matter of attracting investors through exhibitions of earlier stages of the project, and even holding auctions of virtual property, reportedly worth tens of thousands of very real dollars. Evidently networks of powerful supporters and patrons (read collaborators) are a concrete reality in the virtual art world too.

As a reasonably organic entity, though nevertheless developed directly as the artist and collaborators have allowed, it is difficult to pinpoint the work’s particular intent. One could say it is a timely experiment in new technologies and social networking tools in the name of art, behind other real world entities including political parties, blue chip companies and activist organisations. Yet, with its overt Chinese motifs and hybrid mix of “China” old and new, replete with construction sites, a Hall of the People, bellowing smoke stacks and random giant pandas – not to overlook our buxom China-babe host, China Tracy – it is also a personal vision rooted in Cao’s own position, amidst a contemporary China that is both incredibly international, yet ever more adept at channeling social and economic change toward questions of the national interest. The RMB City webpage explains the project by saying:

“China’s current obsession with land development in all its intensity will be extended to Second Life. A rough hybrid of communism, socialism and capitalism, RMB City will be realized in a globalized digital sphere combining overabundant symbols of Chinese reality with cursory imaginings of the country’s future.”

While RMB City raises such questions, it reaches no conclusion, remaining ambivalent at best, appearing at times to merely reiterate modes of social, cultural and economic ‘progress’ its developers and critics claim to address.

In recent years, following the artist’s own earnest involvement with the internet, many of Cao’s video works have been uploaded onto the web. For example, three installments of the exhibited video piece ‘i.Mirror’ are currently on YouTube; and arguably such works seem to make more sense when seen in an online environment. As the current exhibition at Shiseido also shows, such works can serve as an introduction to the less accessible world-within-a-world of Cao’s online experiments, however this does not necessarily translate into the gallery space. Cao’s project, even if indirectly, may seek to blur the very function of sanctioned art spaces nowadays, however well after the tension of cross-discipline or allegedly high and low, fine and popular cultural boundaries have been crossed, the artist is banking on the symbolic value-added of such spaces. The shorter video works, such as “Master Q’s guide to Virtual Feng Shui in RMB City” (2009) are almost uniform in their combination of kitsch pseudo-Chinese motifs in music and graphics, seemingly content to fuse “tradition” in the form of narratives around cultural concepts, such as Feng Shui, into the virtual world. While this is undeniably a technological achievement, the results are less than impressive.

There are aspects of this project overall that are poignant, if not prescient comments on China, contemporary urban development, social networks and technology, as well as the expanding territory of art and the artist. Like much in China at present, despite appearances of bold public scope for myriad development projects, these are also often built on very personal visions. Behind the virtual grandeur of the project’s choreography, like Second Life itself, RMB City remains a personal document of the artist’s explorations of her own identity; in other words, for better and worse, it is at base a personal journey into which we are apparently invited. Packaging this for a Real Life exhibition, divorced from the interactive experience from which it derives meaning, easily renders the motifs of Cao’s virtual creation into mere eye-candy -– allowing them to be plastered as wallpaper in the gallery space. Apparently defying irony, the time, money and personal connections invested into making such an authentic art-world simulacra remains real in every sense.

Cao Fei / China Tracy, 'Live in RMB City' (2009) Video

Cao Fei / China Tracy, 'Live in RMB City' (2009) VideoOlivier Krischer

Olivier Krischer