Making sense of ‘Collapse’

Could there be a better motif for the 20th century than that of “collapse”? Discourses of ideology, religion, aesthetics, even vision itself, have all in some sense, at some point, ‘collapsed’. Yet, despite the conceptual lure cast by the exhibition title, a “sense of collapse” seemed clearer in my mind only due to that which seemed lacking in pieces, ‘reinterpreted’ from the MOMAT collections.

Admittedly, many discourses have ‘collapsed’ due to direct pressures, such as wars, and such ‘collapse’ often remains contested, believed by some–in theory or in practice–to remain structurally solid; or to paraphrase Foucault on Modernism: ‘dead but dominant’. Hence the spaces we inhabit, practically and theoretically, are built on the vestiges of those who were here before. This exhibition takes re-interprets particular pieces of the MOMAT collection to illustrate a new approach to vestiges of ‘collapse’ in 20th century art, as interpreted by the curators. The possibilities for this ‘Modern Art’ museum to reposition part of its collection seemed exciting, and should be applauded. However, the current exhibition seemed to struggle for coherence overall and failed to live up to my expectations.

Of the six works displayed in “Chapter 1”, titled “The World Picture Being Dismantled”, first we find Picasso, then Paul Klee and Max Ernst. The works span a period of 60 years, encompassing both world wars, and seem to be aimed at illustrating the ‘collapse’ of Academic Realism at the hand of Impressionists, Cubists, Surrealists and so on. Religion may also have been an underlying concern for a few artists: we see a Star of David in Klee’s 1916 work, which now seems like a tragic omen of worse horrors yet to unfold in the subsequent decades.

Beside these works was Takako Araki’s stoneware piece, Bible of the Sand; a gritty, buried bible wrought in detailed stoneware, which seemed to continue the surrounding themes: ideological and aesthetic collapse, crises of faith versus persistent dogmas, and so on. However, while this work is exhibited in the first section of the show, the exhibition notes place it in ‘Chapter 2’, titled “Collision Between Nature and Artefact”. Neither is it the first work of ‘Chapter 2’, making me wonder how the structure of the notes corresponded to the exhibition layout. Furthermore, having been produced in 1992, it post-dates the other works by at least four decades. While none of these points are necessarily problems in themselves, together they had disorientating effect and made it hard to appreciate the exhibition as having a coherent idea behind it.

The exhibition includes 45 artworks by 21 artists, divided into 5 conceptually themed “chapters”, and yet two of those chapters each feature a series by a single artist. Thus it seemed burdened by an overly complex structure, which seemed to spread works very thinly in order to cover more predetermined conceptual ground. This encourages one to abandon the exhibition notes altogether, and walk through ‘freestyle’ to intuitively piece together one’s own ‘sense of collapse’.

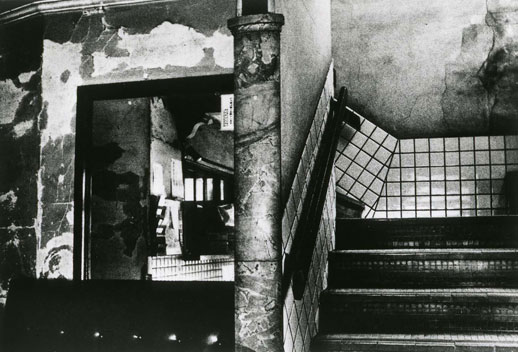

Culminating with Yoson Ikeda’s in-situ pencil-sketches made directly after the Kanto earthquake of 1923, and Ryuji Miyamoto’s photographic series ‘Kobe 1995 After the Earthquake’; it was clear that the thematic abstraction of the earlier sections had given way to documents of physical ruin as direct historical artefact. Under the title ‘Encounter with Catastrophes’, the psychology of ‘collapse’ was here simply depicted the world (or in this case, the nation) gripped by natural disaster, possibly even suggesting a triumph over adversity.

Later, wandering through the MOMAT permanent exhibition; I saw the leaps, twists and turns in the styles of “Japanese art” through the 20th century, which seemed to say something richer about the possible nuances of ‘collapse’ as a 20th century experience, rather than a formal motif.

One work in the exhibition exemplified this crucial difference. Poignantly “untitled”, Kazuo Kemmochi’s 1989 work dominated the main exhibition space, in size and dynamic. Applying oil paint and oil stick directly onto a huge photograph mounted on panel board, the layers of photographic realism are all but invisible under the dense sticky black-brown that promises to envelope the whole image space, charging toward a single point within the composition. The sheer intensity of that point in the painting is like a black hole slowly sucking up its surrounds, silent in the knowledge that screaming would be boring and predictable.

This “sense of collapse” carries with it that horribly exhilarating feeling: the knowledge of what might come next – you don’t want to look, but you can’t turn away. To the extent of their ambiguity, the many possibilities in Kemmochi’s work, made me feel some “sense of collapse”, achieving something more tangible than exhibition’s many illustrations or documents of ‘destruction’—whether destructions wrought by natural disaster or artistic rebellion.

—

1 Note that some works were also supplemented from the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto.

Olivier Krischer

Olivier Krischer