Love’s Body

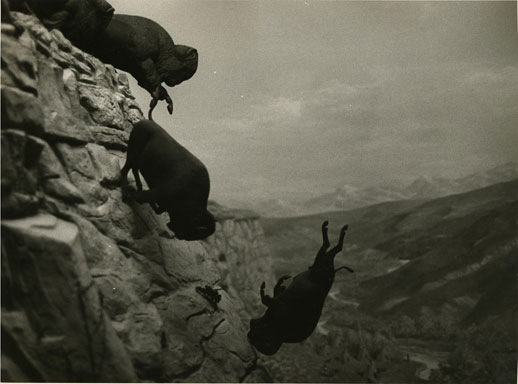

They got it all wrong: In order to advertise their new exhibition, the curators at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography chose some of the more puzzling images, starting with David Wojnarowicz’s falling buffaloes that though quite powerful and esthetically accomplished, doesn’t really convey the real sense of the project. That’s a great pity because “Love’s Body” is a haunting, deeply moving exhibition that approaches its subject (AIDS and its influence on the art community and society at large) from many different angles; from the lyrical to the personal to the head-on political. Another merit of the exhibition is that it successfully avoids beautifying AIDS, fully displaying instead the daily struggle of the infected people who have to fight not only the disease itself but popular prejudice and intolerance as well.

Half of the eight artists featured here actually died of AIDS-related causes. Of the four, Wojnarowicz is the most explicit in condemning societal bigotry and violence, as exemplified by the stark ‘Untitled (One Day This Kid…)’, a grainy photocopy-like image of a child surrounded by a printed text that lists all the troubles awaiting the boy from the moment he “discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.” Together with Akira the Hustler’s video installation and clay figurines (a curious choice for a photography museum) his colorful works (a mix of photos, acrylic, spray paint, and collage) add a welcome diversity to the collection.

The other two highlights of the exhibition are A A Bronson and William Yang. Bronson, founding member and only survivor of the influential group General Idea (responsible, among other things, for popularizing mail art networking) welcomes the visitors with three giants works: ‘Anna and Mark, February 3, 2001 — a bill-board-sized image of a hirsute man cradling a newborn child — is a celebration of life; a necessary gesture “after being surrounded by death for so many years,” he said. On both sides of this work are two larger-than-life photos of Bronson himself (‘The Hanged Man #2’ and ‘#4’) portraying the naked artist with his hands tied behind his back, suspended upside down by a rope that is secured around his ankles.” According to him, “there comes a moment when it’s impossible to control your life. You just have to stop and wait.”

On the same theme of mourning lost friends, William Yang — an early chronicler of the emerging Australian gay community in the 1970s and 1980s — shows in the “Allan” series the last eighteen months of his ex-lover’s life. The nineteen black and white pictures follow Allan’s slow but irreversible decay up to his death, until one gets to the very last image – a portrait of the man when he was younger and healthier. It’s a poignant, moving moment that together with the photographer’s handwritten notes that accompany the pictures highlights the confusion and, ultimately, the utter tragedy of living in a world that rejects you because of your sexual inclinations.

Randy Swank

Randy Swank