Japonisme x Impressionism x Japonisme

Hokusai and Japonisme at the National Museum of Western Art takes a broad look at the Ukiyo-e master’s influence on the Impressionists and others. A short walk away at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, the focus is on Vincent van Gogh and his relationship with the country he loved but never visited in Van Gogh and Japan.

Following the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa, Japan opened its borders after over 200 years of isolation. Japanese art spread throughout the world and became a source of inspiration for art, design and fashion, particularly in Europe. When Japan presented its cultural goods at the World Fair in London in 1862 and Paris in 1867, kimonos, fans, parasols, lacquerware and screens became a craze among the European public. Their popularity gave birth to a new movement, Japonisme.

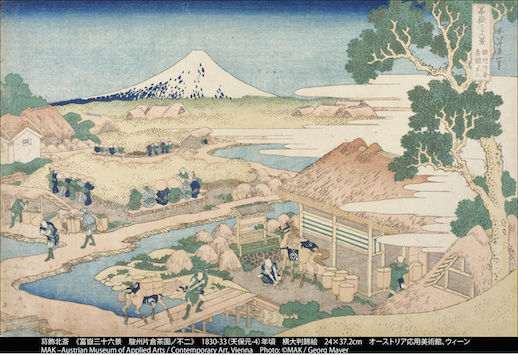

One of the key sources of this influence was Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Brought by the Dutch merchants who were allowed to trade out of Nagasaki, Ukiyo-e had been available in limited numbers in Europe in the 1700s and early 1800s. Now, as household goods flooded into Europe, Japanese prints were an instant hit among Western artists. Their exotic colours and differing use of space all gave new inspiration to these artists’ own work.

The first part of “Hokusai and Japonisme” juxtaposes Hokusai manga volumes with illustrations from Dutch, French and British books about Japan. All are at least inspired by if not lifted entirely from his volumes. He often went uncredited. Despite this, his style was recognisable and very quickly Hokusai was referred to as Japan’s greatest painter.

Collectors started actively amassing Japanese art, with many competing to own the best Ukiyo-e collection. Among them was Van Gogh. Few artists in Holland studied Japanese art at the time that Vincent Van Gogh began his interest in Japan. Beginning in 1885 in Antwerp, he collected Ukiyo-e prints and books about Japanese art and culture. He copied Ukiyo-e in oils in order to understand their composition. However, Van Gogh’s love affair went beyond that. The idealised, light-hearted Japanese artworks provided inspiration both through their composition and their subject matter. Van Gogh stylised Japan in his mind and developed his own utopian vision of the country.

When Van Gogh moved to Paris in early 1886, it was the Impressionists and their inspiration from Ukiyo-e that he found the most arresting. The colour pallette, outlines and style of perspective contrasting with Western art norms influenced these artists in different ways.

Another fan was Monet, who displayed over 50 of his favourite pieces in his living room with pride, with more all over his house. He strove to complete Hokusai’s ‘Large Flowers’ series. Monet’s Bed of Chrysanthemums (1897) is presented alongside Hokusai’s Chrysanthemums and Bee (1833–1834), demonstrating the huge influence Hokusai exerted on the Impressionist master.

After looking at the dissemination of Ukiyo-e, both exhibitions then move on to its specific influences on Western art, be it human figures, animals, plants, or landscapes. In some cases this influence was quite explicit, in others more subtle. An example of the former is the showcase painting at “Van Gogh & Japan” – His Oiran (1887) is a copy of sorts of the Ukiyo-e by Kesai Eisen. Van Gogh found her on the cover of the May 1886 issue of Paris Illustré, an issue devoted to Japan. Van Gogh takes Eisen’s original and then works it in his own inimitable style. He also makes some cross-cultural interpretations using symbolism from both Japanese and Western art. The oiran’s obi is fastened at the front rather than the back and this identifies her as a courtesan. Around her, he painted a pond with bamboo stalks, water lilies, frogs and cranes – the French words for crane (grue) and frog (grenouille) were both used for prostitutes.

The “Hokusai and Japonisme” exhibition is a culmination of years of analysis. The influence of Ukiyo-e on Western art is demonstrated quite obviously, with Hokusai prints displayed next to the art it was meant to have inspired, for example Degas’ Dressed Dancer at Rest, Hands behind Her Back, Right Leg Forward (1896-1911) vs. the image of a sumo wrestler from Hokusai’s Manga Volume 11 (1819). However, it does at times lead to some tenuous links. A woman combing her hair from Hokusai’s The Illustrated Byways of Home Learning Volume 1 (1828) is presented alongside Berthe Morisot’s Young Girl Braiding Her Hair (c.1893) and Edgar Degas’s Woman Combing Her Hair (1896-1899). Surely there are only so many poses that one can adopt in illustrating such a scene?

It is great to see that the “Japonisme” exhibition doesn’t shy away from Hokusai’s more risque works. In a separate section his Shunga is highlighted, with its influence on Rodin and Klimt explored. Although not displayed, it is tough not to think of some of Egon Schiele’s works without seeing the Hokusai influence.

Ceramics, glassware and jewelry were also influenced heavily by Japonisme, with Hokusai motifs incorporated into designs from Emile Galle, Haviland & Cie and Alexis Falize/Antoine, amongst others. There are some stunning examples including Elkington & Co’s Vase with Crane (1876) and pieces from the Service “Rousseau” from Felix Bracquemond and Francois-Eugène Rousseau. Hokusai’s influence went beyond just France and Holland. Scandinavian and Slavic artists are also highlighted, such as Väinö Blomstedt and Arnošt Hofbauer.

Of course, no retrospective on this era could escape the impact of Hokusai’s most famous print The Great Wave Off Kanagawa (1829–1833). Its influence is shown on Seurat, Lacombe, Henri Guérard, and many others, and is clear in works such as Gustave Courbet’s Waves (1870) and Claude Monet’s Sea at Belle-Ile (1890-1891).

Arles, where Van Gogh moved in 1888, frequently became his little piece of Japan. “I’d like you to spend some time here, you’d feel it”, he wrote to his brother Theo after a few months in Arles. “After some time your vision changes, you see with a more Japanese eye, you feel colour differently”. His move to Arles coincided with a shift in his interest. He had no need for Japanese paintings, he wrote to his youngest sister Willemina, because Arles was so much like Japan. However, he did need these paintings. Ukiyo-e continued to influence him in various ways – both as paintings and also in their reproduction. Van Gogh’s dream was to set up an artists’ commune in Arles in the vein of the isolated communities of Buddhist monks. However, only Gauguin joined him.

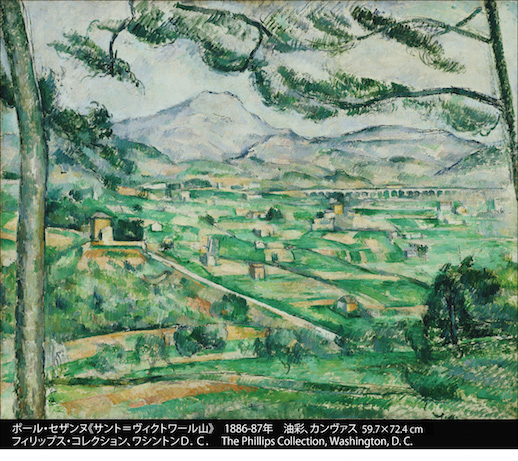

Another major influence Hokusai held over Western art was the popularisation of the concept of series, such as his ’36 Views of Mount Fuji’ (1830–1832). The NMWA exhibition comes to an end with some examples of these. The most direct is of course the ’36 Views of the Eiffel Tower’ lithograph series (1902) by Henri Rivière. We can also cite Cezanne’s portrayals of Mont Sainte Victoire and Monet’s ‘Haystacks,’ ‘Poplars,’ ‘Rouen Cathedral’ and ‘Mount Kolsaas.’ He frequently thought of Mt. Fuji while painting these series.

The influence of Japanese serialization is also seen over at the Van Gogh exhibition. Whether it was Hokusai, or Hiroshige’s ‘Fifty Three Stations of the Tokaido’ (1833–1834), several series from Japan influenced Van Gogh’s ‘Olive Orchards’ (1889). Olive Grove (1889) and Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers (1889) are both displayed.

The Van Gogh exhibition takes a different direction to its conclusion. It flips its focus and deals with the many Japanese who “discovered” Van Gogh after his death. It took twenty years after his death for Van Gogh to become known in Japan. In the 1920s, Japanese painters and literati were drawn to Van Gogh’s work and made pilgrimages to visit his last resting place at Auvers-sur-Oise in France. The family of Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet cared for Van Gogh in his final days in Auvers-sur-Oise and kept three guest books. These books, on loan from the Guimet Museum, are exhibited for the first time in Japan, showing over 240 Japanese people who visited.

Van Gogh’s influence can be seen in a number of works by Japanese artists on show, such as Gihachiro Okuyama’s woodcut modeled after Van Gogh’s The Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887). Okuyama’s work is styled after Van Gogh’s 1887 portrait of paint supplier and art dealer Père Tanguy, who is portrayed against a background of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints.

These exhibitions are not just about one country’s influence on another. They highlight the dynamic interplay between cultures that has been at work throughout human history, a poignant reminder in these increasingly isolationist times.

Mac Salman

Mac Salman