Japanese Expanded Cinema Revisited

Since its re-opening last September, TOP Museum has featured a string of blockbuster shows where the viewer more or less knows what will be on display. From Nobuyoshi Araki to Hiroshi Sugimoto, you have an idea of what you are going to get! The strong curation and popular stars of these exhibitions translate into ticket sales, of course, but every now and then it is nice to go into a show not having a clue of what to expect and come out with a whole new knowledge set. “Japanese Expanded Cinema Revisited” will do that for most.

Japan’s expanded cinema movement developed around the mid-1960s in reaction to experimental cinema in America and Europe. It caught on quite quickly in Japan, consisting of multi-projection, loop projection, and live performances utilizing the technology and multi-media art of the time. Filmmakers wanted audiences re-think the conventional cinematic experience. To illustrate this, TOP Museum presents expanded cinema films in their entirety (no longer than 15 minutes), along with film posters and two installations – one of which features 18 slide projectors centered around a 360 degree screen. Creating a sequence of moving images from stills, this display has been reconstructed for the first time in half a century.

It is surprising how much of expanded cinema had been overlooked in the context of Japanese film history, making the exhibition that much more special as a single compiled source of knowledge about the movement. The onset of the 1960s concluded what is often considered the Golden Age of Japanese cinema, when a new sensibility prevailed as the postwar youth entered adulthood. Studios seized this opportunity and gave emerging directors the chance to make youth-oriented films following the success of the French New Wave, recognizing the low budgets these directors required to make profitable films. Shochiku’s studio picked up Nagisa Oshima, Kiju Yoshida, and Masahiro Shinodo; Nikkatsu, meanwhile, drew in Shohei Imamura and Seijun Suzuki. Then there were the avant-garde independents such as Susumu Hani, 8mm filmmakers like Nobuhiko Obayashi, and Sogestu Art Centre’s Hiroshi Teshigahara making films with writer Kobo Abe.

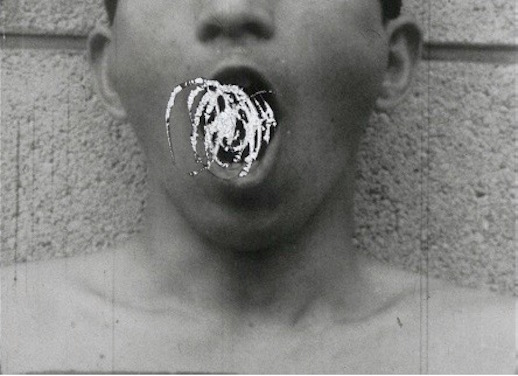

The aesthetics of Japanese expanded cinema for the most part feature no narrative structure, plot, or other conventional cinematic devices. Its films are strikingly similar to those of the late 1920s, when film as a medium was reaching a high point with Soviet montage, the Dadaists and Surrealists in France, Expressionists in Germany, and early exiles like Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau in the U.S. Japan even had its own avant-garde with films like A Page of Madness in 1926. This amazing period came to end with advent of sound, and cinema would largely be neglected as a cutting-edge art form in Japan until the 1960s. Expanded cinema’s editing techniques and non-narrative expressions of political ideas are very Soviet. One of the exhibition’s political shorts even features opening puddle shots similar to Sergei Eisenstein’s Strike. Another film screened, Takahiko Iimura’s A Dance Party in the Kingdom of Lilliput (1964), harps back to French Dada films with overexposures, intentionally scratched prints, and fragmentary combinations of multiple art mediums. Overall, these films share a sense of liberation from traditional constraints in favor of personal expressions of national identity and culture.

Toshio Matsumoto’s For the Damaged Right Eye (1968) is perhaps the masterpiece of Japanese expanded cinema. Presented in the hallway before entering the show, this film says everything the exhibition does about a wide range of cultural phenomena from the 1960s, using multiple projectors that shift between documentary footage and avant-garde cuts. Maybe even more symbolic, though, is Takahiko Iimura’s Dead Movie (1964), an installation featuring an old projector with a black film loop of no image at all. The projector is lit up in the darkness, casting only its own shadow on the white wall – A fitting eulogy for cinema’s approaching death.