The Black Glass of Satsuma: Satuma Vidro

Kiriko glass. Elegant cuts weave geometric patterns in clear and colored glass. Tokyo’s Edo Kiriko is what many people think of when they hear those words. It’s true, Edo Kiriko has a long, solid history, but in actuality, there is another place on the island of Kyushu, far from Tokyo, that also has a kiriko tradition. Satsuma Kiriko comes from Kagoshima, and it has been getting a lot of attention lately for its black designs, called Satsuma Kuro Kiriko. Using a traditional folk craft that had been revived after years of dormancy, and a technique using black glass that was previously thought to be impossible, Satuma Vidro has been making a name for itself. We spoke to Tsutomu Deshimaru about his work as a kiriko glasscutter.

Q: First of all, could you give me a quick sketch of what your studio, the birthplace of Satsuma Kuro Kiriko, is all about?

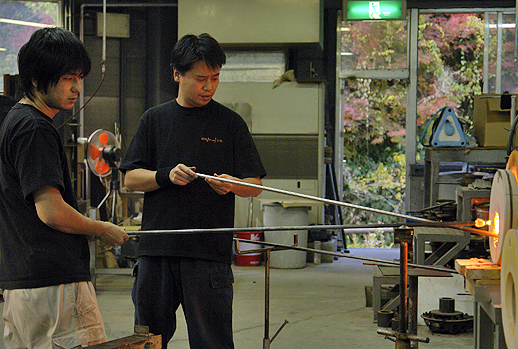

A: Satuma Vidro is a workshop that was established by a man named Yukio Kato in 1994. He’s a real glassblower, right down to his bones. Kiriko (cut glass) is made by a glassblower who makes the glass and then a glasscutter who cuts the pattern into the glass, and he was the former. He was born in Tochigi, but he plied his craft in Tokyo. He became quite well-known for his skill, and it seems he made quite a lot of money too. But one day, he got a request to lend a hand in the restoration of Satsuma Kiriko, and he came to Kagoshima. After several years of ups and downs, in the end he established Satuma Vidro.

Q: Now, Mr. Kato is the president of Satuma Vidro, isn’t that right?

A: Yes. He’s seventy years old now, and he’s been working as an artisan since he was fifteen. He’s been through a lot. He’s worked everywhere, from tiny neighborhood glass workshops to huge glass manufacturers, and he knows about everything there is to know about making glass. He’s got some very interesting stories from the old days.

Q: I imagine it must have been much harder back then for artisans like him.

A: It does seem that way. They only had the first and third Sunday of each month off. The temperature in the glassblowing studio was always fifty degrees. Even in summer, they had only one electric fan. If you talked back to your superiors, they beat you. You had to wash their work clothes for them with nothing but a scrub brush and a bar of soap. Even then, they wouldn’t teach you a single trick of the trade. They stood the risk of losing a lot of money if their skills were leaked to a rival.

Q: He suffered in ways we can’t even imagine today. But how did one become a skilled artisan under such conditions?

A: In the world of the artisan, you know they say “You learn by stealing skills with your eyes.” That’s how Mr. Kato learned. He thought hard about, “How can I succeed at this?” And he decided that he had to learn how to use the furnace in the glassblowing workshop. So he decided he had to get on the good side of the person who stoked the furnace fire. He helped out carrying the heavy coal from the first floor to the second floor. And just as planned, the stoker said “Sorry to make you do such hard work,” and they became friends. And so he was allowed to use the furnace, and he stole their techniques with his eyes and made them his own.

Q: So, does that tough culture live on in your workshop here?

A: No, Mr. Kato decided that “wasn’t any good” and it hasn’t survived. He’s very kind when he teaches. He says he believes “If I yell uncontrollably, people shrink away and it stops being a place for learning.” Mind you, he does get angry sometimes, but he never does so in the morning. “If I get angry in the morning, I get a terrible feeling in my chest for the rest of the day,” he says. Now, if an artisan wants to learn some new skills, they’re free to use the workshop as much as they want. If you want to learn, you can learn a lot.

Q: Mr. Deshimaru, when did you dive into this world?

A: I became a kiriko artisan when I was eighteen years old. It has been almost twenty-four years now since I started doing this work.

Q: Why did you decide to become a maker of such a rare traditional craft such as Satsuma Kiriko?

A: I have always loved making things. Plus, I had always thought I wasn’t suited for a regular office or sales kind of job, and I didn’t want to do that kind of work. So with that, my high school teacher told me about Satsuma Kiriko and I thought, “Why not?” and got him to take me to the workshop. That was the first time I was exposed to it and I thought, “Woah, I didn’t know there was such a thing!” and “I was born and raised here but this is a world I know nothing about.” That’s when I started getting interested in it. I figure if my teacher had taken me to a pottery studio then, I’d probably be a potter right about now. (laughs)

Q: Wasn’t it difficult to restore a lost tradition and establish your own skills?

A: Well, I learned the main techniques by getting an Edo Kiriko craftsman to come and teach me. And then in order to reproduce the original Satsuma Kiriko, I used a book of photographs of Satsuma Kiriko that is stored at a local museum called the Shoko Shuseikan and looked at the photos as I worked. I’d look at the two dimensional pictures and imagine how they’d look as three dimensional objects as I worked, and used methods used in other parts of the country as examples. At first, I was consumed by trying to figure it all out. But I gradually began to get the hang of it. If I do this, then it’ll go like this; I started to develop and understanding after a while.

Q: Could you give me a quick rundown of the manufacturing process?

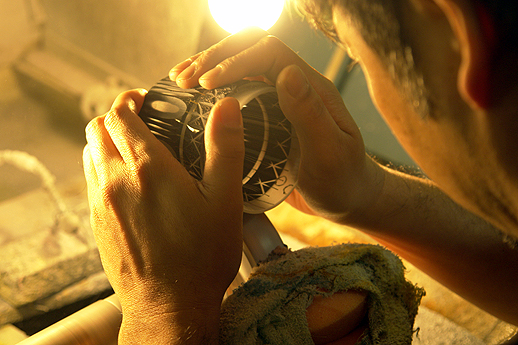

A: First, we etch lines on the surface of the glass. These lines are called “atari” and they become the guidelines for when we carve the patterns. Next is called “arakezuri” where we make rough cuts. We run water while pressing the glass against a spinning wheel that is embedded with industrial-grade diamonds, and carve into the glass. By doing this, the surface becomes like ground glass. Next, we finish the cut with something called “ishikake.” We take the rough-hewn glass and carve the finer parts of the pattern and smooth the rough edges. Then, the final step is called “migaki.” This is where we use a variety of different tools to polish every line and surface of the glass, one at a time, until the whole thing is shining.

Q: The most distinctive feature of Satsuma Kiriko is the “bokashi” – the color gradation. Exactly how is that achieved?

A: First of all, I want you to understand that Satsuma Kiriko is made with clear glass which has been glazed with a very dark colored glass. We cut into the glass at a very oblique angle, which results in a pattern of very shallow, wide cuts. Where the cuts get deeper, and closer to the clear glass, the color gradually gets lighter, creating a gradation. Edo Kiriko is made by cutting the glass at a very acute angle, and the cuts make a very sharp, defined pattern in the glass. All in all, we make the “bokashi” gradation by cutting into the glass at a very shallow angle.

Q: You developed your black Satsuma Kiriko line for the JAPAN BRAND PROJECT, and it looks like it has become quite a hit, hasn’t it?

A: Now, if you want to get your hands on one of those products, you have to wait for at least three months. We make each one by hand, and we just can’t seem to keep up with the demand.

Q: The most popular highball glass costs over 70,000 yen, but even so you can’t keep up with demand. That’s amazing. And they say the economy is bad these days…

A: Most of our customers are of the upper income bracket, but we do have some regular people save up their money and come to buy things from us as well. Also, regarding marketing, I personally go to make demonstrations at events all over the country, and that usually results in a boost in sales.

Q: The black kiriko certainly does exude an air of quality, even to my untrained eye. Could you tell me where you got the idea to make such a product?

A: Our marketing people said, “Kagoshima is home to so many things with “black” in the name – vinegar, sugar, pork, salt, beef, and more. If you want to make kiriko that reflects its Satsuma, Kagoshima roots, why not black kiriko?” But it’s easier said than done. You try to carve black glass and you can’t see a thing from the inside, so it’s like cutting in the dark, with just your sense of touch to guide you. The natural response of our artisans was, “There’s no way we can do that.” But I knew if I went back to the marketing guys and they told me, “What, you can’t do it?” then I’d never live it down. (laughs) So I gave it a shot and tried a few different things.

Q: I see. You attempted something that was generally accepted as impossible among kiriko artisans.

A: It’s a matter of doing the cuts with just your sense of touch as a guide. It’s rather dangerous. But while I was trying various methods, I found, “What’s this? It’s not as hard as I thought!” and I made it. (laughs) That’s why it’s sometimes important to listen to people who don’t know much about the technical side of things.

Q: And now your product has become a hit product, with both the media and the buying public. What are your reflections on how this has come about?

A: I really gained a renewed appreciation for the value of having a skill that no one else can copy. But, since making just one or two per day is the most we can handle, it’s painful to think about it from the business angle. I’m the only one who can do this work, so now what I’ve got to do is teach it to my younger staff. But teaching something like this takes a long time. We’re talking years, at least ten years. As factory manager, that’s a big worry for me right now.

Q: I see. Now, Mr. Deshimaru, tell me what your dreams are for the future.

A: In short, I’d say “global expansion.” We’ve already gotten some feedback from countries overseas, particularly Europe. Quality-wise and technically, I believe we can’t be beat. So just as people now say “Baccarat is another name for glass.” I want to have our name so well-known that one day people will say, “Satuma Vidro Kiriko is another name for glass.” But what I can do as an artisan is continue to refine my skills. Right now, in addition to manufacturing products for sale, I’m working on reconstructing every item in the old photo collection of Satsuma Kiriko pieces. There are over one hundred items, and I’ve done about a half to two-thirds of the work now. I’m going for a clean sweep.

Satuma Vidro Industrial Art Nagano 5665-5, Satsuma-cho, Satsuma-gun, Kagoshima

A Word from a Regional Project Participant

Two of the most beautiful traditional products to come out of Satsuma are Satsuma Kiriko glass and Oshima Tsumugi fabric. Here at the Kagoshima Prefecture Federation of Society of Commerce and Industry, we chose those two products to develop into world-class brands through participation in the JAPAN BRAND Development Assistance Program. We started the project in 2005, and named it “The Collaboration of Beauty and Technique that Satsuma Takes Pride In.” Two of the things we particularly put our energy into with this project were participating in conventions both domestically and overseas, and public relations activities. We went to conventions in France, Austria, and Germany. The manufacture of both products requires highly skilled artisans every step of the way. Since everything is done by hand, it’s really not possible to mass produce these products. We decided that working to let more people know about the products, improving marketability, was the best way to incorporate them into peoples daily lives. A theme of our project was, “Making products with warmth and color that comes from black.” With Satsuma Kiriko, Satuma Vidro succeeded in developing black kiriko into a product, and it has been accepted by the market, and I think their activities have had a positive influence on the other local manufacturers here in Kagoshima. With Oshima Tsumugi fabric, rather than using urban distribution channels, we tried developing new products through retail sales distribution channels. The brand name is SOF. We developed a variety of smaller items such as scarves, sweaters, bags, and so on. Oshima Tsumugi is produced on the island of Amami Oshima, and the distances involved make coordination difficult. But from now on, we will take our time, maintaining good relationships with each manufacturer, and work towards bringing vitality to these rural areas.

Japan Brand

Japan Brand