Into the Light

Enter the New Photography of Japan at the onset of the 1930s, a movement influenced by Germany’s New Objectivity with parallels to what Rodchenko and the Soviets were doing. Japanese photographers sought to heighten creative expression in ways only possible through photography, maximizing the mechanical nature of a camera and lens. The basis of the New Photography movement is explored in The Magazine and the New Photography: Koga and Japanese Modernism at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. The first section, “Trends Overseas,” spotlights those who influenced the Japanese modernists, among them Moholy-Nagy Laszlo and Herbert Bayer of Bauhaus in addition to those mentioned above. The Japanese photographer Sen’ichi Kimura and a few others with photographs taken on study tours to America and Europe at the beginning of the 1930s are also included.

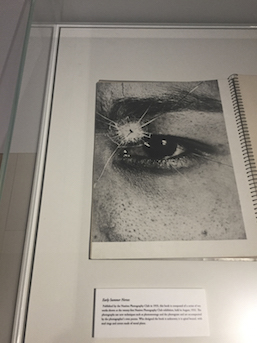

The second section, titled “The New Photography,” sets into place conceptual foundations of the movement according to critic Nobuo Ina, who characterizes New Photography as a mode of expression attempting to: 1) grasp the subject objectively and accurately and discover new beauty; 2) document lifestyles and report on human lives; and 3) use the photogram and photomontage, creating with light. These aims were achieved by the two short-lived publications Shinko Shashin Kenkyu and Koga. The former was a not-for-sale journal of three editions limited to 200 copies each, and exhibition catalogue actually offers a reprint of all three issues. The latter was a bit more expansive, with 18 issues printing the work of over 70 photographers including foreigners such as Edward Steichen and Eugene Atget.

The final section “After the New Photography” shows the natural progression of the movement, which pronged into two directions: pure individualistic expression and social commentary device. With the international rise of Surrealism and Abstraction, Japanese photography also moved into the avant-garde directions. From photo experimentation emerged montages and the dark room techniques of the French. Much like the Soviets, some used similar techniques of propaganda. Overall, the photographic ideas of the time were quite innovative, as looking at photography as what can be done solely with the camera and darkroom allows for limitless creativity. “The Magazine and the New Photography” offers a refreshing look at possibilities so often overlooked in pure photography in this digital age.

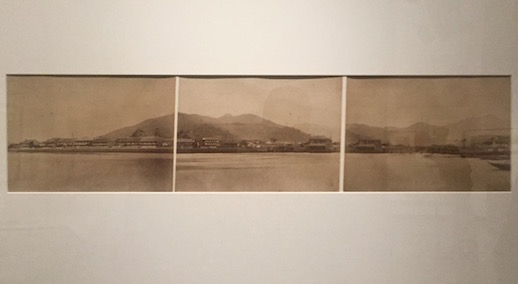

Also at TOP Museum, the ambitious Geneses of Photography in Japan: Nagasaki celebrates the Meiji Era’s 150th anniversary through a series of exhibitions chronicling the birth of Japanese photography. Certainly more anthropological in nature, this show serves as a good contrast to “New Photography.” It tells the story of how Japanese photography began in the country’s oldest open port city of Nagasaki, focusing on the closing years of the Tokugawa shogunate through the early Meiji period. A lot of the Western technology that came to Japan was brought through this port, and along with it came the first daguerreotypes and Western photographers arriving to shoot this new land. Curiously, it was landscape photography and not portraiture that made the earliest visual account of Nagasaki. Even more interestingly, panorama photographs colored by hand were favored. The photographers achieved this by taking subsequent shots on a tripod and splicing the individual photos together. In that manner they are almost like Ukiyo-e scrolls in the way they unfold. This free online dating service is a great place to find any type of dating. You can search for singles by location san antonio personals sex, age and many other things. You can also chat and flirt with like-minded individuals on the Internet. If you’re looking for singles in San Antonio, try the local San Antonio dating sites. In the transition from feudalism to a modern society, Nagasaki proved to be among the most dynamic cities in Japan.