Into the Atomic Sunshine

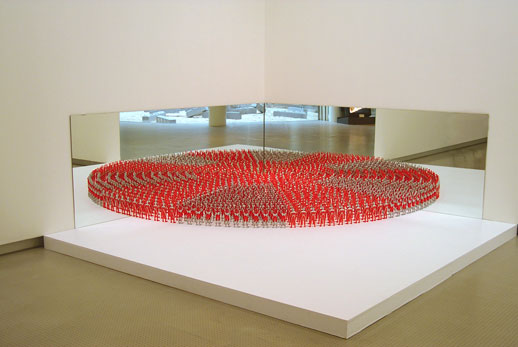

A horde of Ultraman figurines stands in concentric quarter-circle ranks, arms raised high up in the air in a gesture of celebration, as though shouting “Banzai!” The triumphant ritual is self-witnessing. Facing mirrors mounted in one corner, they are smirking at themselves, at their own solipsistic victory.

What does winning mean without a referee to pat you on the back? Without the losers sticking around to act as a compensatory reminder and benchmark for one’s own success?

“Into the Atomic Sunshine”, an exhibition themed after Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution1, visualizes this state of ambivalent peace that has prevailed in the country for more than sixty years without a single direct instance of armed conflict. Or so it seems. In Yuken Teruya’s photograph, a filigreed chrysalis hangs delicately off the upturned barrel of a pistol: an implement of death lies dormant, just like the unborn insect coccooned snugly just next to it. There is a certain precariousness to the whole arrangement that nonetheless seems to hold together, perhaps a metaphor for postwar Japanese “peace”, underwritten by a tangled web of politics and poised near crisis, but with all the deceptive tranquility of a still life.

Motoyuki Shitamichi’s “Torii”2 photo series reminds us of these now-hollow symbols of empire that litter the former colonies and protectorates that used to make up Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. These tokens of imperial rule have now either fallen into disuse, or shed their context and found second lives. In one photo of a park in Taiwan, a torii has collapsed in a central plaza and come to be used as a bench. Since the end of the war, these now faded trophies have changed hands among different “victors”. And yet, while Taiwan may have regained its independence from Japan, somewhere like Saipan has instead since been re-annexed to the US. The torii diaspora in these photos thus illustrate a lineage of successive colonization and subjugation, perhaps most strikingly dramatized in one photo of a lone torii gate standing in a Christian graveyard, almost hidden amongst the accumulated ranks of tombstones, cherubic statues and icons of the Virgin Mary. Instead of foreclosing further war hostilities and takeovers, Japan’s neutering via Article 9 was perhaps nothing more than a prelude to the licensing of subsequent, more “valid” territorial reshufflings.

Where once Japan saw itself as a key axis around which world events would unfold and develop according to such spheres of military influence, Article 9 has, since its imposition, also ensured a steadily advancing sense of the country’s re-isolation from the world. Yukinori Yanagi has visualized this in a somewhat simplistic but effective metaphor titled Banzai Corner, the aforementioned installation of Ultraman figures. Standing in ranks against a mirrored corner, they cheer and are cheered on by the image of their own reflection. “Banzai” shows us the lonely elation of the virtuoso propped up by his own self-regarding reflection. In one sense, this phalanx of superhero figurines is what contemporary Japan has labored to achieve: homogenous success on “peaceful” fronts, the result of declaring unilateral demilitarization, opting out of a messy international fray, and away into a radiant one-sided (mostly economic) victory in a corner.

Or perhaps Banzai Corner is something more chillingly literal: a toy diorama that depicts a largely puppet Self Defense Forces, invoked and justified as self-defense in puzzling contradiction to the resolute stance of non-violence promulgated by Article 9. These are Ultramen who promise to save Japan from an alien invasion, but the metaphor can be extrapolated to any number of other postwar anime or manga set in a plausible future where superheroes save Japan from apocalypse. Any official state-based or national conflict suppressed by Article 9 provokes an underground, subconscious reimagining of what was foreclosed but may someday come to be: this is the subliminal and often fantastical level at which conceptions of national defense take root, a historically resonant hypothesis that lurks in the imaginations of Japanese pop subculture.

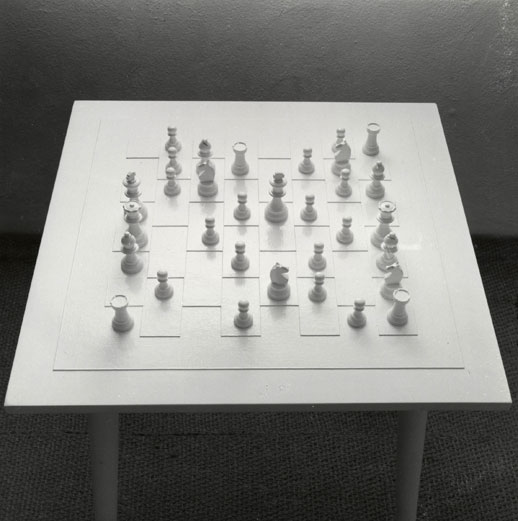

Imposed peace, of course, is no real peace if latent aggressions still simmer beneath the nominal situation. What was imposed by Article 9 was only the military, inciting-through-aggression form of armed conflict that today has receded into its own corner, so to speak. Sovereignty of the state, border conflicts that erupt along the fault lines of national borders, the nation-state itself as a participant in war and its determining principle – these are largely obsolete notions in the face of a more total and perpetual sense of omnipresent war, interwoven into society and disseminated throughout it. Taking this as a starting point, Yoko Ono’s White Chess Set (1966) captures this sense of neutralization, helpless stalemate, and the end of definitive partisanship: in this work, which literally consists of an all-white chess set, one is unable to distinguish between friend and foe, and as the game progresses becomes assimilated harmlessly into a generalized condition of home ground. Japan’s disavowal of military involvement sixty years ago was thus perhaps a prefiguring in advance of this state of total “Empire”, as much a condition of peace as it is of “war”, as theorized by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt. Although it was made four decades ago in response to the Vietnam War, when considered in light of domestic social ruptures that began to take terrifying form amid the economic uncertainty of recessionary Japan in the 1990s — the 1995 Aum Shinrikyo subway gas attacks in particular – Ono’s White Chess Set dramatizes this sense of being marooned and confused about the character and origin of the threat at hand.

Taken as a whole, “Into the Atomic Sunshine” strikes a unique note that otherwise seems missing from locally curated thematic exhibitions in Tokyo – a mix of didactic irony about political issues, and an increasingly glazed-over and defeated sense of stasis and arrested action. On the other hand, if Article 9 is invoked here as a central clause that has dictated postwar politics, art and culture, there are no instantiations of those things here – except perhaps Yasumasa Morimura’s video A Requiem: MISHIMA 1970.11.25 – 2006.4.6, a reenactment of Mishima’s pre-suicide speech that reprises its impassioned lament of cultural entropy, slavish imitation and loss of “spirit” in early 1970s Japan (although Morimura here means to berate the state of Japanese art for roughly the same problems more than 30 years later). Surprisingly, not a single anime- or manga-related work, among many that directly treat issues related to future rearmament, apocalypse, and the psychology of defeat, has been included. Perhaps the sense of ambivalence hanging over Article 9 and its nominal, externally sanctioned condition of peace might be better read between the frames of Gundam or Space Battleship Yamato.

—

1 Which states: “Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and

order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

2 the gate marking the entrance to a Japanese shrine

Darryl Jingwen Wee

Darryl Jingwen Wee