Identify Yourself

We are all fully aware of our own height, weight, ethnicity and what part they play how in how we view ourselves. But what about the other physical attributes of our bodies that are uniquely ours? This is the crux of ‘The Definition of Self’, an exhibition which takes a fascinatingly broad look at the issue of identity through a variety of cutting-edge technologies.

Exhibition director Masahiko Sato usually divides his time between his role as Professor at Tokyo University of the Arts and his work as a communication designer. Previous projects of note include educational television programmes (most famously NHK’s ‘Pythagoras Switch’), a video game (the PlayStation title I.Q.), and several well-received exhibition works.

Sato and his collaborators for this show have all put a great deal of effort into making “The Definition of Self” a fully interactive, bilingual and thought-provoking experience. While the majority of exhibitions focus on the artist or a muse of his choosing, this show takes its key concept of ‘identity’ and makes every single person a participant. Our appearance, our behaviour, and even our reactions are all factors under the spotlight.

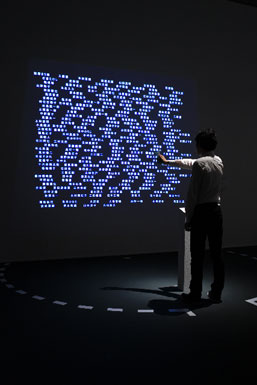

Starting off, Euclid’s ‘Pool of fingerprints’ is one of a number of exhibits developed in collaboration with giant electronics companies. Viewers scan in their print which is then transferred to a lightbox pool. We can then watch as it wriggles into life as a seemingly sentient being and joins the mass of previously-birthed fingerprints.

Starting off, Euclid’s ‘Pool of fingerprints’ is one of a number of exhibits developed in collaboration with giant electronics companies. Viewers scan in their print which is then transferred to a lightbox pool. We can then watch as it wriggles into life as a seemingly sentient being and joins the mass of previously-birthed fingerprints.

‘The Nominal Divide’ (Euclid, again) made me feel decidedly nervous. Here, facial recognition cameras — developed by the ominous-sounding Omron corporation — present a series of gates where the audience has to choose a path and await the camera’s judgment on your appearance. Despite getting my age bracket wrong (take that, Omron) it’s an unnerving example of the technology being developed at the moment.

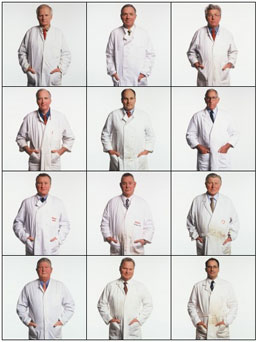

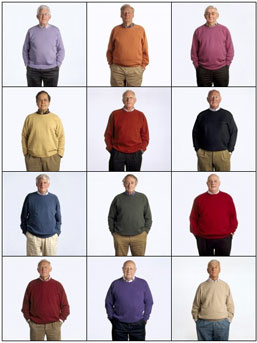

‘Exactitudes’ by Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek is a photographic experiment created between 1994 and 2009 documenting and organising people into stereotype groups. Some of the group labels are hardly P.C. (“Casual Queers”, “Mister Wang”) and the general look a bit stock photo-like, but the thought of being judged and put into such groups does disturb the inner need for individuality which many of us in the audience naturally have.

‘Height meets Weight’ (by Euphrates and Masasuke Yasumoto), ‘Attributes Inherent in Your Behaviour’ (by Euphrates) and ‘2048’ (by Hisato Ogata and Masahiko Sato) all utilize information given by the visitors upon entry to great effect. Seeing the names of people who share the same height and weight connects the viewers in a way I’ve never seen before, and always manages to bring out a laugh or a smile. ‘2048’ on the other hand had the opposite effect. Viewers cross-check their retina scan with the audience database, before the exhibit singles out your name with cold, sinister accuracy.

Musicians Sheena Ringo, Keigo Oyamada (Cornelius) and brain scientist Kenichiro Mogi are amongst the contributors for ‘The Mess in our Heads’, a collection of laptop computers displaying their (presumably real) cluttered desktop arrangements. Despite the big names, there are no clues as to whose computer is whose, and the chance to discover something about them is unfortunately lost.

Out of the twenty-two exhibits, those with a technological slant tend to have the greater impact. The reference works, such as the Jomon period clay tablets and ‘Lost Property’, while completely different, each offer questions for the viewer to consider.

As you leave, the final part of the show gives the Japanese participants a corner to write to Sato directly with their thoughts (which he duly responds to, by letter in the entrance upstairs). As the only part of the show which isn’t bilingual, it’s also the only disappointment in an otherwise magnificent show.

Paul Heaton

Paul Heaton