Honoring the Legacy of Kenzo Tange

With the conclusion of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, Japan may be traversing down memory lane with similar sentiments as after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Not only did two of the country’s top architects, Kenzo Tange and Kengo Kuma, leave behind symbols of modern urban architecture with Yoyogi National Gymnasium and the New National Stadium, there remain historic links between their works. Kuma has always regarded Tange as his foremost mentor and a catalyst in his decision to become an architect. It was not coincidental, therefore, that the New National Stadium extended the design philosophies of the first gymnasium from 57 years ago.

Further, the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games and the coming Expo 2025 Osaka bring to mind the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the Osaka World Expo 1970, both of which involved the designs of Tange. These reminders of his architectural legacy have prompted the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs to embark on an extensive investigation of architectural documents related to Tange’s significant works. The exhibition “Tange Kenzo 1938-1970: From the Pre-war Period to the Olympic Games and World Expo” runs until October 10th. It traces for the first time Tange’s footsteps from his student years at Tokyo University through the post-war reconstruction of Japan with photographs, plans, models, and video clips. It explores the roots of Tange’s skills in conceptualizing architecture, cities, and national infrastructure.

This tribute to Tange is organized into five sections: War and Peace, Modernity and Tradition, Postwar Democracy and Government Building Architecture, Challenge to Massive Space, and Designs in Information Society and High Economic Growth. The integration of all these themes is reflected in Tange’s most momentous achievement in the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, which is presented both in the initial and final rooms of the exhibition. This monumental structure continues to this day to be an essential living testament to postwar Japan’s economic resurgence and embrace of urban modernism. It is thus considered as Tange’s magnum opus.

The architectural plans, photographs, and scale models impress the visitor with the enormous scope of Yoyogi National Gymnasium’s design, engineering, and embedded spiritual philosophy. The stadium is flanked by Meiji Shrine and the former site of Washington Heights (the U.S. Armed Forces housing complex during the occupation), conveying the message of world peace after the war. Tange believed that pillars obstructed the link between the athletes and spectators, so he devised a lightweight, suspended roof system with a cable structure to achieve a large space. This system had never been attempted in such a large building before the gymnasium. Tange also added spiritual elements through the interior cross-section with the kanji character for 8 (hachi) emitting light through the cables, representing the connection of heaven and earth. He employed a similar technique in St. Mary’s Cathedral.

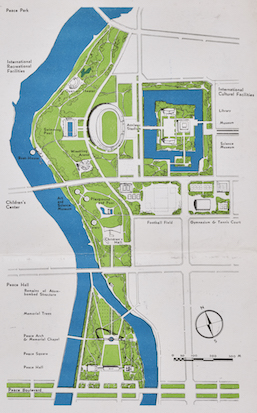

One of the highlights in the exhibition is the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, completed in 1949. The conceptualization of this symbolic monument was both a personal endeavor and a crucial challenge for Tange, who sought to build an eternal space that would connect the war survivors with the dead. Tange attended high school in Hiroshima, and it was here where he first discovered Le Corbusier in an art journal. He regarded Corbusier and Walter Gropius, a Bauhaus movement founder, as geniuses of architecture, and he was heavily influenced by their philosophies. It has been said that the Hiroshima memorial’s flat roof, pilotis-style of elliptic pillars, and louvres were signature Corbusian elements. A huge model in the exhibition heightens one’s perception of how Tange ingeniously laid an axis running vertically from the Atomic Bomb Dome across the river toward the south side of the site to the Peace Boulevard, so that the dome and the people could face each other.

We can also view the architect’s previous residence in Seijo, Setagaya, built in 1953. Once again, evidence of Corbusier’s influence is seen in the pilotis style and transparent glass walls of the second floor. Rare pieces of modernism by Isamu Noguchi and Taro Okamoto that decorated Tange’s home are also on display.

Tokyo residents may be familiar with St. Mary’s Cathedral in Mejiro, built in 1962. Tange continued to express a transcendental view by again fusing spirituality in space with a cross-shaped plan and vertical frames of hyperbolic paraboloid shells, which he claimed symbolized community in medieval temples.

Other works on display, such as the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, the Kagawa Prefectural Government Office, and the former Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Yurakucho, encapsulate the celebrated architect’s ideals of true modern architecture. Instead of being hampered by negative aspects of urban expansion due to economic growth, Tange sought to “eliminate evils” by perceiving cities dynamically through concentric development. He allowed structures to extend from the center of the city (self) to the periphery (suburbs), establishing linear growth. As one of the prominent leaders of the Metabolism movement in Japan, Tange remains as a vital force in the incorporation of tradition and modernity in design—a legacy that he has passed on to many outstanding Japanese architects today.

Alma Reyes

Alma Reyes