Hiroshi Sugimoto “Lost Human Genetic Archive”

The Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (Syabi) has reopened its doors with a new international feel, a new name (Tokyo Photographic (TOP) Art Museum), and a rebranded design. As the museum celebrates its 20th anniversary and reflects the increasing internationalization of the city in the lead up to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, it is perhaps fitting that the institution relaunches with a solo exhibition by Hiroshi Sugimoto, a New York-based, Japanese-born photographer who first gained his fame outside of Japan. “Hiroshi Sugimoto – Lost Human Genetic Archive” consists of three series: a Japanese version of his 2014 Paris exhibit ‘Lost Human Archive’, a new installation entitled ‘Sea of Buddha’, and the world’s first showing of `Abandoned Theater’. In addition, works by winners of the 59th World Press Photo Contest can be seen on the basement floor.

Most shocking about Sugimoto’s main show on the third floor is how little photography it actually comprises. More like an archeological mission than a photography exhibit in structure, “Lost Human Archive” presents 33 perspectives on the world’s end in the near future. Providing commentary on current global economic issues, each explanation from sources ranging from an idealist to a militarist, car salesman, and beekeeper begins with: “Today the world died. Or maybe yesterday” (a play on the opening lines from Albert Camus’s novel The Stranger). To offer visual context, Sugimoto pairs each story with items from his collection of historical artifacts and everyday objects, as well as a photo from series of his own, such as ‘Seascapes’, ‘Dioramas’, ‘Lighting Fields’, and ‘Portraits’. This “Japanese version” of the exhibition is significant in comparison to its Paris counterpart, as the majority of the artifacts are from American WWII collections that honor American heroism against the Imperial Japanese. The very same items placed in the context of this show change the meaning to question the state of civilization. The exhibition comes off Duchampian in its ability to counter the ways we perceive the objects and their subsequent values. Each of the 33 stories is written on traditional Japanese paper to match the aesthetics of the work, and visitors are given handouts printed with these stories (English and Japanese are available).

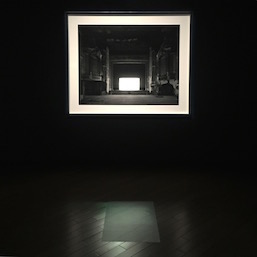

The “Abandoned Theater” series on the second floor is similar to another series in which Sugimoto took long exposures of a movie playing at a theater on an 8×10 full-frame camera…only now in abandoned cinemas. These images are presented in darkness, as if actually in a movie theater, with the name of the film and a synopsis projected on the ground in front each of photo. Sugimoto chose the films based of the aesthetics of the theaters. Themes of decay and the passage of time carry over from the rest of the exhibition.

On the opposite side of this room is the “Sea of Buddha” series, which photographed the Senju Kannon Statues at Kyoto’s Rengeo-in Temple (Sanjusangen-do) in 1995. The temple was built in the twelfth century, when people believed in the Buddhist philosophy of Mappo, foretelling the destruction of civilization and the extinction of humanity in one thousand years’ time. This brings the exhibition full circle, as the Japanese name of the temple translates to 33 – coinciding with the 33 perspectives on the future end of civilization in “Lost human Archive”. The images themselves are presented in a backlit row projecting light into the darkness. Much more preferable was Sugimoto’s installation of the same images at the Hara Museum in 2012, when he presented each in an accelerating slide show, giving the statues the feeling of moving toward the viewer before they sped by so rapidly they melted back into one image. In this display, the photos seem shown merely for their symbolic factor, relating to the overall theme rather than standing on their own like the other two installments.

This exhibition may seem a better fit in a contemporary art museum, although it is significant not only of the TOP Museum’s new direction, but of photography itself as it expands as an art form and becomes digitized with works that can sell for the price of paintings. “Sugimotos” are highly valued in the art market, while Gursky, whose photos made the high-art world take photography more seriously, command as much as 4 million USD. Martin Parr may have expressed it best when he said the benefit here is that the money trickles down to all photographers and expands what the medium can do. More importantly for Sugimoto himself, who has since gone into architecture, landscaping, stage design, and writing bunraku plays, is challenging the idea of what an art photographer can be.

As a final note on TOP’s relaunch, the library has been renovated along with the rest of the building. One of the biggest appeals of the museum has always been this archival collection, which is free and contains some of the rarest photo books in existence today, made available to anyone who requests them through a simple bilingual computer system. It would have been wonderful to see an expansion and more promotion of this special facility, especially considering Japanese photography has always been about the photobook. Outside of Japan the greatest photographers did their best work on commissions, and eventually these works would be published in book form as an afterthought. Japanese photography is unique in that photographers from the Provoke era and after shot with the photobook entirely in mind. Let’s hope museum features this amazing collection more prominently, taking the opportunity to teach the public about an aspect of the medium that makes Japanese photography unique from the rest of the world.