Becoming Fashion

Once one recognizes the fictional nature of photography, and, like Hiroshi Sugimoto, openly discusses it as a constructed untruth, the question then is: What value do photographs have as documents? Moreover, can they ever really harbor any kind of didactic or critical potential? “Hiroshi Sugimoto: From naked to clothed”, the current exhibition at Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, demonstrates how photographs produced and understood by this framework can indeed be exploratory and informative.

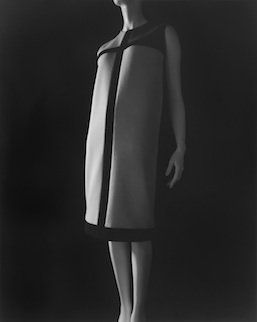

According to the exhibition notes, in creating and/or assembling the thirty-odd works on show, Sugimoto “sought to uncover the essence of what it is to be human”. This statement is telling of Sugimoto’s academic background; he studied Hegel, Kant, and Marx in the Faculty of Politics at Rikkyo University, Tokyo. Searching for an “essence”, the photographic images – about two thirds of the exhibition is photography – feature models rather than human beings. For Sugimoto, the focus is on the telling nature of clothes; “[o]ur clothes don’t become us, we become our clothes.”

Whilst addressing the performative function of clothes and prioritizing garments over bodies, Sugimoto perceives humans as actors; “we are the guise of self we put on… We wear clothes to play our everyday selves.” This overwhelming responsibility afforded to the external explains his use of fake rather than real life models. The absence of physical bodies has no bearing on locating the human “essence”, hence it is that which adorns the figures that is the focus, the models molded to fit their needs.

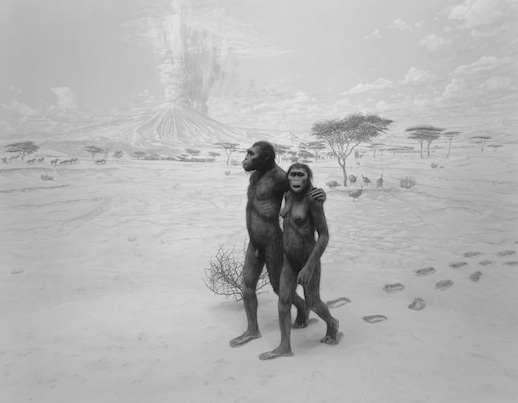

Arguably his belief that the internal “essence” is somewhat consistent and quantifiable is a view heavily indebted to Western philosophy. Unsurprisingly, his “Western orientation” extends to both the “Portraits” and “Dioramas”. Primarily lining the first floor corridor, these images present a history of clothing from the prehistoric era up to the last century. Beginning with ‘Homo Ergaster’, which shows two early humanoids crouched in an arid landscape surrounded by birds of prey, the series ends with a 1930s Mae West. With this, the lineage explored here is primarily European and North American, including a scene of the plague and an image of Spartacus, for example. Similarly, the portraits on show right at the entrance to the exhibition are of the English king Henry VIII and his six wives.

A noticeably Asian (or, more specifically, Japanese) dimension to the exhibition doesn’t really feature in the history depicted thus far. Instead, it is located upstairs, as if with a deliberate divide. With three Rei Kawakubo pieces and garments by Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake appearing in the photographs on the second floor, the most contemporary clothes included are nearly all of Japanese origin. To accompany this, and possibly draw further attention to it, original clothing items made by Sugimoto, such as ‘Ikazuchi-mon “Thunderbolt Pattern” Noh Costume’ (2011), are also on display in the rooms adjacent. This separation of “East” and “West” seems to echo Sugimoto’s own learning and education; he didn’t study Oriental philosophy until later in his life, not developing his interest in Zen Buddhism until he had left Japan and was living California. In this way, the history that this show outlines is clearly more personal than universal.

Returning to the subject of “performativity”, it is difficult to look at these images, predominantly of female models and garments for women, without remarking on the gender binaries upon which they rely. In addition to the “Stylized Portrait” series that is entirely female-centered, the prehistoric diorama scenes feature distinct males and females. Gender is clearly an important factor for Sugimoto. The performativity of gender, as a way of understanding how individuals represent their identity externally, has been influentially discussed by Judith Butler in her book Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (1993). Butler’s theorization shifts the focus away from the flesh of the body, where gender has traditionally been rooted, and instead concentrates on external codes such as clothing. Sugimoto’s way of thinking somewhat mirrors Butler’s here, locating identity cues outside of the body.

However, unfortunately the parallels between Sugimoto and Butler must stop here, for the images on display in “From naked to clothed” lack the drive to problematize the rigid boundaries that society uses to hem “identity” in. There is no deviation from the normative in this exhibition. In attempting to answer the question “What does it mean to be clothed?”, Sugimoto has presented a show that fully acknowledges the hegemonic role that clothing has played, and continues to play, but without challenging this at all. Consequently, viewers are provided with an exquisite whistle-stop tour through select eras of history and fashion, painstakingly photographed with awe-inspiring precision. The result is a visually stunning show that displays the artist’s impressive technical ability and his very good eye for fashion, even if he does believe “[w]e were happier long ago when we lived naked.”

Jessica Jane Howard

Jessica Jane Howard