Higashiyama Kaii Retrospective 1908-1999

Kaii Higashiyama (1908–1999) graduated from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts before studying in Germany. During this early period his paintings were frequently shown at the Kanten (Japan’s government-sponsored art exhibitions). Upon his return to Japan, however, he was drafted into the Pacific War. During the war and its immediate aftermath he lost his home, his father, mother and brother.

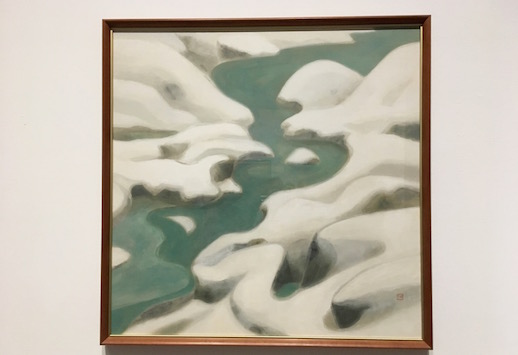

Despite the hardships, Higashiyama emerged into his own after World War II. His oeuvre is on display in Higashiyama Kaii Retrospective 1908-1999 at The National Art Center, Tokyo. His works from 1947-1953, shown in the first section of the exhibition, display a distinct contrast to three earlier paintings from 1941. Higashiyama’s colour palette became more muted, his shapes defused but distinct. This change can be seen when comparing Nature and Forms – Stream and Snow (1941) to Ravine (1953). The latter demonstrates what would become the artist’s signature style––a sympathetic, almost abstract yet fundamentally realistic contemplation of nature.

Higashiyama’s works during this period are giant landscapes void of animals or people, yet they are engrossing. You feel captured inside––seeing the leaves, smelling the grass, feeling the mists dampen your face.

Given the importance of this era in his career, it is worth highlighting that two of his most famous masterpieces from the period are also on display, Afterglow (1947) and Road (1950). Road shows a small countryside road (originally based on a sketch from Tanesashi in Hachinohe) that stretches vertically upwards, perhaps symbolizing both Higashiyama’s artistic journey and the country’s unclear yet optimistic path of rebuilding after the Second World War.

Where Higashiyama could not find the subjects he was looking for, he created them in his own mind, as in Autumn Shade (1958). This creation of ideal landscapes was to feature much more heavily in works created in the last twenty years of his life.

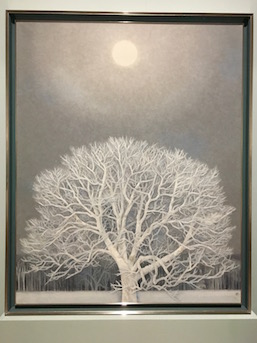

In 1962 Higashiyama travelled to Scandinavia, seeking to shake up a comfortable existence of winning awards and producing commissions for the Imperial Household as his popularity steadily rose. He fell in love with the reflections of the landscapes on calm lake surfaces, a theme he returns to multiple times, such as in Reflected Images (1962) and Blue Marsh (1963). Winter Flower (1964) is a quintessential painting of this period––a white tree is in the lower foreground with white, narrow trees lining up on the lower background beneath a gray sky illuminated by an orb––it is unclear whether it is the sun or moon. The entire work is painted in shades of white and gray, evoking Egon Schiele’s Autumn Tree in Stirred Air (Winter Tree) (1912). Both Higashiyama and Schiele’s trees can be considered allegories for the human condition, and despite the different feelings they evoke, both succeed in creating analogies of life.

We can contrast these natural Scandinavian landscapes with the urban scenes Higashiyama painted in Germany and Austria, which he departed for in 1969. He had last lived in Germany almost 40 years earlier, and upon his return focused on buildings and townscapes––a radical departure from his usual natural landscapes. The show is enhanced by displaying these works.

Higashiyama believed that painting was akin to prayer. So it is fitting that some of his most monumental works are the murals from Miei-do Hall at Toshodai Temple in Nara. Higashiyama was inspired to create the murals by his deep respect for the eighth-century Chinese priest Jianzhen—known as “Ganjin” in Japan. After five failed attempts to journey to Japan, during which time Jianzhen lost his sight, he eventually made it and founded Toshodai. This connection with China is more relevant given that 2018 is the 40th anniversary of the Japan-China Peace and Friendship Treaty. Higashiyama travelled around Japan and made three trips to China to seek inspirations for his murals.

The recreation of the murals is no mean feat, keeping up NACT’s tradition of mind-blowing installations, such as the 1:1 recreation of Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light for the architect’s “Endeavours” retrospective last year.

Higashiyama’s ‘Landscapes with a White Horse’ are also presented. The backgrounds are typical natural scenes, except for the presence of a small white horse, which Higashiyama explained as “a manifestation of my prayers for peace of mind, reflecting a mental state that required prayer”.

Higashiyama is most famous in the eyes of the Japanese public for his paintings of Kyoto, primarily because of the “Four Seasons in Kyoto” exhibition held in 1968. He created his Kyoto paintings in preparation for an Imperial Household commission in which he was asked to produce a mural for a new palace.

In his final twenty years, Higashiyama painted with as much vigor as ever. Unable to travel around Japan as much due to deteriorating health, he painted landscapes from his imagination, assisted by the copious notes he had made in his younger days. Perhaps it is in this period that we find more clues to his enduring popularity: his representations of the human condition as seen through a Japanese lens, of ties to nature and the soul, and of the ephemeral nature of our time on Earth.

Mac Salman

Mac Salman