Ghost Fires

The other segment (ended January 5) screened four blocks of shorter works as brief as three minutes and as long as sixty. Although this part has ended, do not be discouraged from seeing the first portion, which is more than worth a trip to TOP Museum. If anything, the stills, video sketches, and short films on display here will build curiosity for Weerasethakul’s longer works, a few of which can be found online. One of his full features, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, is occasionally on Netflix.

The title “Ghosts in the Darkness” shares its name with a beautiful essay by Weerasethakul in the exhibition catalogue. For him, “ghosts” allude to invisible beings featuring significantly in his art. His interest is in the duality of these supernatural forms, contrasted in nearly plot-less direction depicting everyday life with natural dialog and very little camera movement. For a juxtaposition with such potential for suspense, these are not in any way horror films. They are symbolically surreal, best demonstrated in a scene from Uncle Boonmee in which the terminally ill lead character sits down for dinner with his sister-in-law and nephew. His wife, who has died decades prior, slowly appears in an empty chair. The three living characters are initially taken aback, but immediately accept her presence and begin a casual conversation. This is all in one medium-long shot with no movement or cuts, and no music. The scene comes off so naturally that is jarring, a perfect example of Weerasethakul’s work.

The notion of ghosts takes on further meaning when seen as representations of things past. The majority of Weerasethakul’s films are shot in his home region of northeast Thailand, an area that has undergone drastic change: What was once a jungle is now a city with a political history as a Communist Party stronghold, the presence of which was largely eradicated by Thai government forces around the time of the Vietnam War. This place is said to be the site of some of the worst atrocities of the conflict between the insurgents and the arms, so much so that anyone involved was killed or ran off, to the effect that very little remains in witness to this history…except for memories. A few of the films touch on this political side while bringing in childhood memories in conjunction with the region’s history. This is an important point in Weerasethakul’s artistic development: his ghosts, rooted in recollections of childhood, have evolved into specters of political memory.

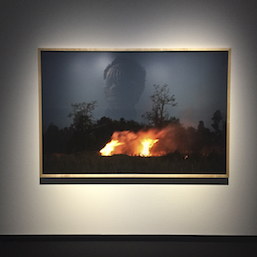

Weerasethakul’s works are all essentially about life, and TOP’s exhibition captures the artist’s notion of life as a cycle. Though understated, The Fire (2009), a photo of a rice field burning, means so much. In order to grow new crops old ones must be destroyed. It is violent yet necessary for creation, a cycle. During a talk Weerasethakul repeatedly spoke of how personal this work is to him. The photo Father’s Clinic (2016) shows the room in which his father had recently died, again pointing to a preoccupation with the continuity of life and death.

Another telling installation is a simple row of books selected by Weerasethakul that have inspired his work over the years. Looking at someone’s bookshelf provides insight into who the person is, and Weerasethakul’s micro-library with authors including Oliver Sacks, Donald Richie, and Yukio Mishima is no different. Mishima and Richie are both major figures of Japanese culture, and Weerasethakul mentioned in his talk that, along with India, Japan has been a vital reference in his creative practice. In terms of their pacing and plot-averse focus on the everyday, Weerasethakul’s films come across somewhere between those of India’s Satyajit Ray and Japan’s Yasujiro Ozu. Remarkably, these three paragons of their national cinemas all take a similarly unconventional approach: Instead of “What happens next,” with their films one must constantly ask, “What is happening?”