A New French-Japanese Project is Set in Motion

“We want to meet the craftspeople behind Japan’s traditional crafts. We want to see their workshops with our own eyes.” These were the words of the leading designers of France’s product design world, Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec. For designers living outside of Japan, even if they have the chance to encounter Japan’s traditional craftsmanship and aesthetics it’s usually through exhibitions. Rarely do they have a chance to visit the people for whom that work is their livelihood, to experience the circumstances in which they do their work, to truly develop a deep understanding. Now, in the first collaboration with a designer from overseas for JAPAN BRAND, kicking off a new project to make products for the 21st Century, the Bouroullec brothers’ demand was one that spoke of their sincere devotion to the project. In late-February of 2009, Ronan Bouroullec’s exploratory mission to the Noto Peninsula in the Hokuriku region of Japan started in earnest.

Interview by Chiyo Sagae

Photos by Tetsuya Ito

Translated by Claire Tanaka

1) Ishikawa Prefecture: Wajima

We were met by members of the Wajima Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and went straight to see the first step in making Wajima lacquer, the forming of the wood core, at the Kirimoto studio. The studio has been around for generations, and these days they do everything from forming the wood to applying the lacquer. At the Kirimoto studio, a number of skilled craftspeople were busy making the cores from local cypress and cedar, and doing each of the numerous steps required to complete a lacquerware piece. Ronan seemed completely amazed as he watched the delicate work required to produce these subtly curved and deliciously plump works. When he heard that all their tools, such as planes and hand drills, were custom made for the user and for the task at hand, he took them in his hands and examined them closely. As a product designer, tools and techniques are naturally a point of interest. He asked detailed questions from start to finish, as if he was spotting possibilities for new forms in each manifestation of the partially completed works. Shunpei Kirimoto, second generation owner of the shop, showed him traditional objects like a sashimi tray and small decorative pieces, and judging from the many photographs he took, Ronan found a great number of ideas in the ancient Wajima works. He also pulled out his sketchpad and drew as he tried to explain tools used in France. It is just this communication across language that comes naturally when a designer and a craftsman meet. This interaction seemed to be a very meaningful part of the visit.

At the Wajima Kobo Nagaya, which was built in the center of town and is designed in the style of the beautiful old row houses of the region, we visited the studio of Yoshinobu Tsuji, where the core wood for kurimono (lathe-turned pieces) such as bowls are made, as well as the studios of Tsutomu Maeno, who applies the base layer of lacquer, also known as the shitaji, Hideo Tanaka and Hiroyuki Yoshida who apply the top layers of lacquer, and Osamu Omori, who applies the makie (a technique where gold, silver, and colored powder and lacquer are applied in delicate layers to decorate the surface) As a roundup, a workshop was held at the facility explaining every step required in the making of Wajima lacquerware, and Ronan expressed great interest in the rustic beauty of the objects at each stage in the process, each which bears little resemblance to the completed piece. The next day, we observed the art of decorating the surface of the lacquerware with Yoshiaki Matsui’s chinkin (the art of decorating a piece of lacquerware by cutting grooves with a chisel and inserting lacquer and gold to make a design), and Kosaku Kitahama’s home studio where he does makie. Ronan Bouroullec saw with his own eyes the techniques, time, skills, and human effort that go into making that stately Wajima lacquerware. How will he put what he has learned into this project? It might have been the time difference, but he said “I woke up early anyway,” and took a sketch of a still roughly-hewn wooden bowl from a pile of accumulated sketches and showed how he had already begun using his hands to think about how to use what he had seen.

2) Niigata Prefecture: Sanjo

The next morning, we headed north from Kanazawa up the Japan Sea coast by express train straight to Sanjo City, Niigata. Ronan gazed out the train window at the many scenes of houses and fields, towns and coastlines that passed by. It seemed as if he was trying to use this short time to burn these scenes of local life and environment into his mind. The sight of him trying to understand even just a little of the local people, land, and lifestyle in order to find common collaborative merits became a common thread running through the trip. A blacksmith from the Sanjo Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Tsukasa Hinoura, came to act as our guide. Sanjo is home to a great number of blade producers, large and small. Mr. Hinoura’s workshop specializes in sickles and the machete-like nata that have been used in the local forestry industry for generations. However in recent years he has expanded to cover a wide range of bladed products. Even so, he works together with just his son doing everything in-house, from folding the metal to be used for the blades, to forging, fine forging, polishing, and quenching. Every step is done by hand with great care. His forge is one of a true craftsman. As Ronan listened to his explanations while looking at the wide range of blades, he said, “Design dwells here.” During the tour of the workshop, he watched the scene with intense interest, as water, steel, and fire seemed to repeatedly clash together in the act of making a blade. Ronan had a detailed question for every aspect of the craft; production time and volume, kinds of knives and their uses, materials used and manufacturing methods for knife handles.

The next day, we visited the company which produces nail nippers recognized worldwide, SUWADA. The third generation president and grandson of the founder, Tomoyuki Kobayashi guided us around. It was here the Ronan focused his attention on the thoroughness at how this company has pursued the ideal form for performing the simple action of cutting fingernails. The nippers, which cut not in a scissor-like fashion but by two blades moving together in a clamping motion, have been continually refined to become the ideal tool for this very specific task. The size and tension of the spring, the introduction of a plate spring, placement of the plate spring, the slight curve of the blade and handles have all been developed gradually over time. The nail nippers that emerged after years of relentless pursuit of an ideal are “a worthy model for the world’s product designers to learn from.” Even in this factory where the fine work is done assembly-line style by several craftspeople, we were able to see how the successful completion of each precision item relies on a human’s touch and sense.

Even as the time to return to Tokyo encroached upon us, Ronan had a strong desire to visit one last shop. We paid a visit to Chuichiro Sone’s bladesmithing factory, Tadafusa, where a certain degree of mechanization has been introduced to the process but the hand of an artisan finishes all the blades. Sanjo is home to many bladesmiths, but each of them has his own beliefs, and in meeting these men who each continue to pursue their own ideals, Ronan said he “feels so many possibilities.” There is no need for a designer to get involved in Sanjo’s highly developed blade craftsmanship. However, how to bring these wonderful products together to where they can reach the consumer? He began to think that it was a possibility and task of the design.

World-class French designers, Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec, have designed new Japanese traditional crafts!

JAPAN BRAND is sending out high quality and techniques to the world. By adding new forms to tradition, new possibilities can be found. To this end, Ronan Bouroullec, of the world-class Bouroullec brothers design team came to Japan on very short notice. He visited one of Japan’s great lacquerware producing regions, Wajima, and Sanjo, a town famous for its knives. It was a journey where he experienced Japan’s legendary craftsmanship for himself. Furthermore, Ronan was inspired by the techniques and processes of Wajima lacquer and created some CG designs proposing products that maintain tradition while exploring new possibilities. There are four designs. This is Wajima’s high-level traditional craftsmanship as reinterpreted through the lens of a French designer. It is an ambitious set of products, trying something new both for consumers and the production area while responding to basic modern needs. With the goal of developing Japan’s craftsmanship onto a worldwide level, we hereby present a “New Tradition” as designed by Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec.

○ These four prototype designs are a presentation that puts a spotlight on the basic charm of Wajima. I considered many other ideas, but I wanted to express the possibilities of the Wajima craft’s traditional techniques to the world; “showing the beauty of lacquer,” “expressing the texture,” and so on not only to the Japanese market, but also appealing to the people of the world who have little to no knowledge of the culture and history of lacquerware.

○ All of the designs contain a geometric sign, which is the project’s trademark (to be inscribed with the “chinkin” method) and it’s intended to increase the overall impact. By including a simple and basic sign to tie the project series together, it will evoke a sense of new possibilities and continuity for Wajima, as well as representing the numerous skills in Wajima such as woodworking, lacquering, and chinkin.

○ The mix of the relatively large lamp with smaller portable objects in the series was part of the concept from the start. The various Wajima crafts expressed through a variety of products increases the impact, and it also allows the possibility of drawing the attentions of a wider range of consumers.

●Project 01: Desk Light

This is the largest piece in the series. It’s a lamp that uses LED to display the beauty of Wajima lacquerware in clear focus, as if it was under a magnifying glass. The goal of the piece is to maintain the functionality of a lamp while also putting the spotlight on the beauty of the lacquer itself. The choice of a lamp was also part of a strategy to sell the product overseas. For example, European people have a hard time understanding why lacquerware is so expensive. On the other hand, a high-quality, well-designed lamp is easier to accept as having a higher price. The light of the lamp itself illuminates the high level of craftsmanship in the lacquer, attracting people to the product. The project turns the focus to the quality of the lacquer by shining a light on it. The light that emits from the lamp will reflect off the lacquer, creating a red glow. This is part of the design as well. It will transmit the unique qualities and mood of the lacquer to the surrounding space.

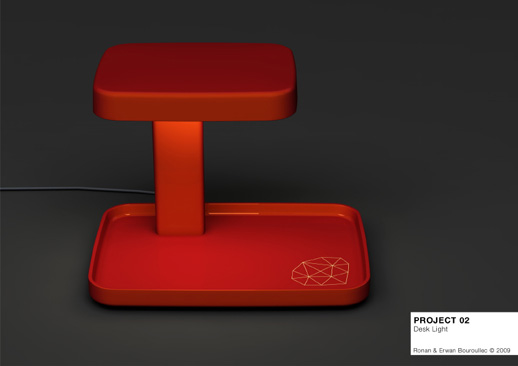

●Project 02: Desk Light

The form is of a tray we are all accustomed to seeing. This is designed by assembling three parts. Each one seems to be a traditional form, but by combining them in an intelligent way, a new product emerges. I wanted the people of Japan and of Wajima to recognize this. By combining traditional forms that we seem to have grown used to and traditional craftsmanship, it can be seen with new eyes. I wanted to draw attention to how many new possibilities there are in what we already have and what we already know. I’m basing the design on a traditional form, so I imagine that to a Japanese person it will resemble a Japanese-style lamp. It’s a very simple yet functional lamp, and it’s a very Japanese design. I like it a lot. By combining what feels to me as a “Japanese” impression, and forms that I believe are already familiar to people, I think this product will give a sense of affinity to many people.

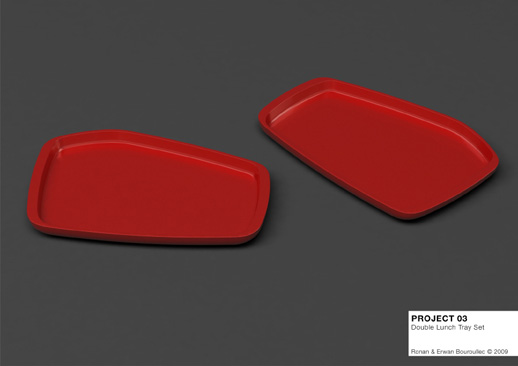

●Project 03: Double Lunch Tray Set

This product uses magnets to hold it closed like a shell, and it opens up into two trays. During my travels in Japan, I became aware of the possibility of using a tray as a dish. French people might use this to hold toast (like a plate) or use it to carry salad or soup that’s in a dish (like a tray). It presents a freedom of use in being available as either a tray or a dish. The lid is exactly the same size as the body, making it two trays (or two plates) so two people could use it at once. The magnetic closing mechanism is to keep dirt from entering when food is stored inside. This makes storage easy, and cleaning is easy too. My original idea was to make several trays of differing sizes but the same shape, which can be nested inside each other like a set of matryoshka dolls. The largest tray would act as the storage vessel for the smaller trays. This nested style would actually be the ideal here.

●Project 04: Pocket Mirror

The largest goal of this product was to express the wonderful texture of the lacquer. In order to do this, I wanted to make a small object that could be held in the hand as a part of one’s daily life. The sense of touch is extremely important. This product is something you can put in your pocket and carry everywhere, touching it every time you use it. It’s also important to let people experience the joy of Wajima lacquerware through touch. Despite there not being many hand mirrors designed for men, they are actually in high demand. By creating a unisex design, I’ve eliminated the “hand mirrors are for women” notion, and created something that appeals to both men and women. I used a piece of stainless steel polished to a mirror finish for the mirror primarily because it is light and affordable. As a result, it is paired up with the luxurious lacquer, giving a light and contemporary impression.

Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec

These French designers are brothers who work in designing products and interiors. Ronan was born in 1971, and Erwan in 1976. Their works have been selected for the Pompidou Center in Paris and the MoMA permanent collection. They continue to design furniture and other products for companies such as Cappellini, Vitra, and Magis. Their sophisticated designs, which feature a functionality demanded by modern lifestyles and a thoughtful consideration for the environment and other factors, have gotten high acclaim the world over. They even took on the interior design for Issey Miyake’s A-POC boutique in Paris.

Japan Brand

Japan Brand