Figments of Our Imagination

Tucked away in a corner of Ebisu’s quiet neighbourhood, Mika Ninagawa’s latest exhibition “Ninagawa Baroque/Extreme” has commandeered all four-floors of NADiff A/P/A/R/T. With arresting photographs from Ninagawa’s new series “Ninagawa Shanghai” and “Tokyo Underworld” along with past collections, it is no wonder that Ninagawa’s popularity extends beyond herself.

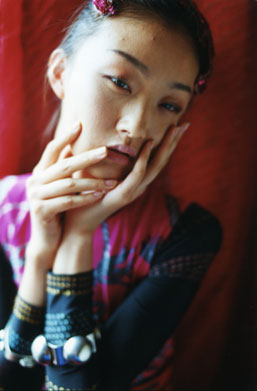

Ninagawa’s photographs are characterized by her signature burst of intense colours, where she mixes seemingly conflicting palettes into something of unearthly beauty. This trait was carried on even when she ventured into directing her first feature film, “Sakuran” (2006). She frequently includes goldfish, flowers and provocative portraits of Japan’s colourful entertainment world as part of her photographic narrative.

So it’s probably not surprising that NADiff’s clean white interior was chosen as the perfect place to showcase Ninagawa’s works. The minimal, almost clinical white walls of NADiff serve as a stark contrast to Ninagawa’s prevalent use of exuberant cobalt blue and blood red, and her photographs seem to jump off the walls.

I personally recommend taking the spiral stairway, located at the gallery’s far right side, as the entry-point into Ninagawa’s fantasy world. Entering from the first floor, where her photographs are strung on laundry-line above, the distinction between “inside” and “outside” is blurred as visitors are greeted with small pockets of colour in the form of her photograph catalogues and goods on display. It’s an easy introduction into the photographer’s work – visitors are not overwhelmed by her visually arresting work and can choose either to go down to the basement gallery or up to the galleries on the second and third floor. This separation between reality and hyper-reality in the layout of the exhibition perhaps is most telling of the layers behind Ninagawa’s works.

In particular, her series of photographs with “Catherine” as her main subject, a garishly made up ganguro, sums up the Underworld succinctly. There is no differentiation between the shock of colours on Catherine’s face, the Chupa-Chup coloured set, and the basement’s walls. They all seem to melt into each other, each another lurid colour overlapping the next. In essence, Catherine, as well as her fellow compatriots in other Technicolor subcultures, loses that defining aesthetic which sets them apart from Tokyo’s monotonous salarymen and greyscale skyscrapers.

There is none of that seedy Tokyo under-belly in her photographs: Japan’s pop culture is truly cool and fascinating, with no infantilization or overt sexualisation of subjects that’s commonly perpetuated as Japan’s now famous ‘otaku’ culture. Ninagawa uses similar subjects: cutesy anime figures, young women in cosplay, cartoonesque sets. Yet all her portraits exude a sense of confidence and assertion that is rarely presented in such settings. Interspersing photographs like Mondo in ruffles and drag, and a pageant of plus-sized ladies, “Tokyo Underworld” presents Ninagawa’s take on Tokyo’s subcultures which are often stereotyped and overlooked as simply ‘deviant lifestyles’.

Moving up to the second floor, “Ninagawa Shanghai” and “Flower Addict” are by far more sombre than the previous gallery. The lighting in “Ninagawa Shanghai” is dimmed and the projector casting photographs onto the far off wall border on eerie. This is a dream-state of a different kind, and it falls in line with Shanghai’s grittier locale. What strikes me as a stroke of ingenuity is how Ninagawa, or the curator, clusters photographs with subtle colour associations together. Each frame has at least two photographs with common colours, and it’s a joy to discover the similarities between photographs which, on the surface, seem to be only beautiful shots.

The final gallery on the third floor culminates in an exhibition which shows Ninagawa’s diversity as a photographer. A collaboration with Japanese starlet Erika Sawajiri, this special gallery is a balance between the sobriety of the second floor and the liveliness of the basement. The collection is controlled, and demonstrates Ninagawa’s skilfulness as a portrait and fashion photographer. Again, her love for bold colours is obvious here, with Sawajiri decked out in voluminous rainbows.

If “Baroque/Extreme” is anything to go by, Ninagawa’s launch into the international arena this year seems promising. Good gallery layouts and set-ups are vital in presenting Ninagawa’s work as mature and globally appealing.

Alicia Tan

Alicia Tan