Exhibiting Modern Traditions

Somebody said that history is written by the victors. But this says nothing of how and when ‘history’ is depicted and displayed, or when it is re-presented. No doubt an ongoing cultural process, it is one in which art often plays a leading role. With this in mind, three recent exhibitions caught my attention for each being titled after a period which is not in itself ‘artistic’ (Taisho or Showa), yet each for adding a word to this period that suggested that here was a new take on history, through art, or at least, via visual culture. What role do exhibitions of art, and more broadly ‘visual cultural’, play in the structuring of the content they “exhibit”? This essay is less a description of recent practice than a comment on the significance and further questions that have come from comparing a few recent exhibitions as a collective represention of recent approaches to considering issues in twentieth century Japanese history and art.

These were:

1) “Taisho Chic”

2007/04/14 – 2007/07/01, Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum

2007/09/08 – 2007/10/14, Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art

2) “Showa Boogie-Woogie 1965-64”

2007/04/21 – 2007/06/03, Kawasaki City Museum

3) “Showa: Photography from 1945 to 1989 [Part I] – Occupied Japan”

2007/05/12 – 2007/06/24, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

Taisho Chic

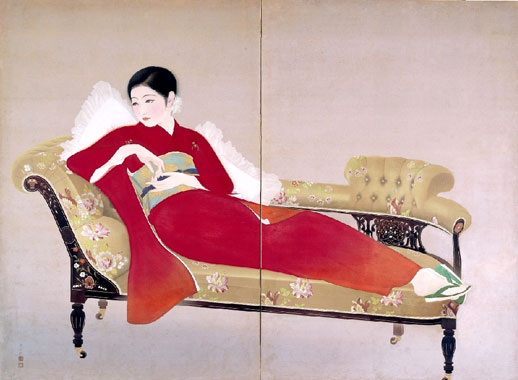

Taisho Chic… ‘Chic’? The word alone made me look twice at the reclining demure nihonga beauty, advertising the exhibition, on a rush hour metro. Resplendent in red and ‘modern’ short coiffure; intentionally alluring, long posed fingers…this exhibition seemed a must-see for someone interested in Japanese modernity: Taisho was the flowering of that modernity in all areas, not least of which the arts. The exhibition was being held at the Teien Art Museum, which I had heard was the art deco former residence of Prince Asaka; even more reason to make the trip. I began to consider it as a small step into the Taisho period (1912-1926).

The exhibition actually draws on work from what is sometimes thought of as ‘greater Taisho’ ; from the 1910s to the 1930s.1 The combination of works and exhibition space at times felt like a walk-in diorama, worlds away from the white-cube gallery. Not only paintings and woodblock prints, but also craft and design, were given an uncanny in situ feel, in the imperial villa turned ‘museum’, itself built in 1933 (early Showa) and principally decorated in the art deco style by a French designer. A Romanesque fresco I noticed on one wall between exhibition rooms also suggested something of art nouveau’s neo-traditionalism. This was an intriguing ‘foreign’ parallel to the dilemma of defining visual modernity that underlies the exhibition’s motivation, and no doubt most of the works themselves. Consciously functioning in-between positions that were later to be separated further. Such art is somewhat misrepresented when under one or the other label. Somewhere between tradition, neo-tradition, and the avant-garde, it is not so readily defined by typically linear art history.

The central image of the exhibition; Daizaburo Nakamura’s (1898-1947) portrait of the young film starlet, Takako Irie, illustrates the modern, personal approach he brought to bijinga, moving beyond the more generic images of ‘beautiful women’ typical of this genre’s tradition, and not only in Japan. Exhibited alongside the final sketch, comparison illustrates the artist’s determined aesthetic intentions. In the sketch–the same scale as the painting, executed in pencil, with some colour highlights–the face is depicted in greater detail, fuller, more realistically fleshy; the figure all-over more tangible. A shawl drapes to the ground, where a cat lies under the chaise-longue. In the painting, however, Irie’s features are simplified, made less specific. The shawl and cat are removed, thus removing those anchors that assured the floor’s visual presence, leaving the young woman and lounge floating in a mysteriously potent open space. Although the very modern coiffure and rich designs of the foreign lounge (borrowed from a Kyoto department store) anchor the work in the ‘now’ of 1930, in the final image–simply entitled Fujo; or ‘Woman’—the artist has opted for the depiction of an ideal, albeit one based on a real, contemporary, model.

Shuho Yamakawa’s Three Sisters (1936), is another image which demanded attention, as much for technique as subject matter. The largest piece in the exhibition, it is monumental in scale yet executed with an incredible lightness of touch. The subtlety of its pale colouring, verging on monochromatic, somehow made it seem almost translucent, and yet glowing. The ‘sisters’ wear modern kimonos, two sit in an obviously expensive new car, one stands confidently; one hand resting on the bonnet, while her other hand casually dangles a new leather-cased camera. They were in fact three daughters of the wealthy right-wing industrialist; Fusanosuke Kuhara (founder of Hitachi among other companies) who would be labelled a Class A war criminal by the post-war tribunal and forced to sell off much of his assets. His daughters were married into other prominent families who had faired better. The image, however, shows nothing of the turbulence of the mid 1930s in which the family would have been deeply involved. Instead, as the catalogues notes, “Shuho’s image of these three elegant sisters radiates utter calm.”2 Yet, a calm that now becomes—to the extent of its oblivious serenity—uncanny, and troubling.

The exhibition’s theme was not so much Taisho art as Taisho representation of women, particularly in bijinga; yet recognising ‘women’ as the prism through which modernity was imaged. Although the typical moga (modern girl) did appear, notably in woodcuts such as Kiyoshi Kobayakawa’s Tipsy (1930), the image of ‘woman’ was not centred on an obviously ‘western’ styled avant-gardism. This differs, for example, from the groundbreaking 1998 exhibition Modern Boy Modern Girl, held both in Japan and Australia. Instead, in Taisho Chic, the contrast of a ‘modern’ individual subject inhabiting an idealised image space is more difficult to reconcile, and yet engaging—visually, and otherwise—for that very reason.

Similarly, approach to early Japanese artistic modernity as ‘hybrid’ has recently figured in another, larger exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art; ‘Modern Art in Wanderings: In-between the Japanese and Western style paintings’.3 In this case late 19th, early 20th century painting works were presented as interesting early experiments; the term ‘wandering’ suggesting that these artists were yet to find their way. However, rather than seeing such work as ‘impure’ anomalies, I think they constituted legitimate options for a number of artists who, as much in technique as in subject matter, moved ‘between’ the alleged ‘poles’ of tradition and modernity.

Many Japanese viewers seemed, like me, to be seeing these kinds of images for the first time. The question then becomes one of what happened next? How is it that a section of tangible artistic output from the late 19th through to mid 20th century, should until recently have been all but forgotten, particularly in the country of its creation? While some works in ‘Taisho Chic’ are indeed exceptional examples of an artist’s oeuvre, viewed together they provide a ready image of turbulent, uncertain times. They also correspond to other aspects of visual culture; in theatre and literature, for example, as well as advertising, and developments in popular culture generally. Popular song-books, with titles such as “Song for Democracy”, “Great Earthquake Song”, or even “Great Tragedy in Nikolaevsk” (referring to the 1920 massacre of Japanese in the Eastern Russian town of Nikolaevsk, leading to the extension of Japanese occupation of Sakhalin), more directly suggested the greater scope of a modern culture, of which these albeit ambiguous paintings and prints were but another aspect.

Showa Boogie-Woogie 1945–64

Where bijin were prisms of modernity in Taisho Chic, Showa Boogie Woogie drew on popular culture to tell a story of post-war reconstruction, capped by the implied success of international recognition with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. This was, strictly speaking, not about art, rather providing a chronological panorama, in the style of a ‘social history’ museum, no doubt befitting its venue; the Kawasaki City Museum.4

Many things are noteworthy about the conception of the period, 1945-1964. When saying ‘chronological’, the exhibition literally began with the day the war ended. At the entrance was a diorama of a ‘typical’ 6 tatami room, circa 1945. It is the afternoon of August 15, 1945; the day Emperor Hirohito publicly announces Japan’s defeat…His stark voice repeats the surrender on a radio, while the daily newspaper; lying on a low table in the centre of the room, bears the same headline. Boogie-Woogie?…I wondered.

Save for this initial jolt, thereafter, give or take a few grim post-war black and white photos (undernourished children, wandering jobless war veterans, black-markets…) the overall image is one of positive growth and yesteryear icons, and while the exhibition pamphlet expressly says it is not simply about nostalgia, it also refers to post-war popular culture in terms of “hope” and “courage”, such as in the popular 1948 tune ‘Tokyo Boogie-Woogie’, hence the exhibition title.

It was fascinating, and slightly disconcerting to notice just how many things I associate with contemporary Japanese society were exhibited as rooted in the ‘past’ of immediate post-war culture. And while the explanatory notes would have it that the 1964 Olympics, and the inauguration of the bullet-train the same year “marked the end of the post-war and the beginning of a new era”, even a brief list shows how many aspects of this ‘past’ persistently define the present. The bijin of the preceding Taisho period has moved onto magazine covers and advertising campaigns. We also find pro-baseball, comedians and sumo wrestlers, each with collectable merchandise; hairdressers and numerous minute variations in hairstyle, cafes (with various French names), the latest consumer technologies, like the earliest black and white televisions; manga, followed quickly by anime, with Tezuka and a universe of cute robots and anthropomorphic characters; cigarettes, department stores, fashion houses, shinkansen and a general mania for transport, pachinko…and so on. Nostalgia for a living history?5

Although an incredible collection of insightful material history was on display, I was still left feeling that in terms of ‘post-war Japan’, emotional gaps were not represented. Where was the collective shock, or deflation? Was introspection simply not part of popular (tatemae) culture enough to be ‘visible’?…I wondered. Perhaps there were allusions to such understandings somewhere within the exhibition, but put subtly enough to elude me.

Showa: Photography from 1945 to 1989 [Part I] – Occupied Japan

In the exhibition, the introductory text boldly stated: “This exhibition is not a nostalgia exercise in recalling fondly remembered times. It revisits the roots of who we are today and, we hope, offers an opportunity to think about who we should be and how we should live our lives.” This was more readily achieved through the medium of photography, with strong documentary work by photographic legends like Ken Domon and Ihei Kimura.

Less definite positions of cultural subjectivity were evidenced in photographs of demobilised Japanese soldiers by Tadahiko Hayashi (who had himself been repatriated from Beijing at the end of the war), or slightly later in Yukichi Watanabe’s The Elizabeth Sanders Home (1950).

A black-market in Ginza, a photograph of famous writers, beggars snapped by Ihei Kimura: perhaps despite itself, this exhibition makes it difficult to distance a sense of nostalgia from photographs of famous places or people, or by particularly famous photographers. That said, some photographs did seem to achieve this. A large assembled image; a 360˚ panorama of the bombed city of Hiroshima by Shigeo Hayashi (1945), taken as part of an official survey of the damage, seemed to provide an immediate window into that time, not blurred by nostalgia or pity. Shomei Tomatsu’s Circus Clown, said to have been a platform for the realist movement in photography, nevertheless reflects something I find more introspective, as much as it is a ‘straight’ portrait. In a different way Kiyoji Otsuji’s nude Objet (1953) remains, even now, a complex image. Installation? Performance? Conceptual portraiture? It suggests something well beyond the ‘Eros and Realism’ title of the section in which it was featured.6

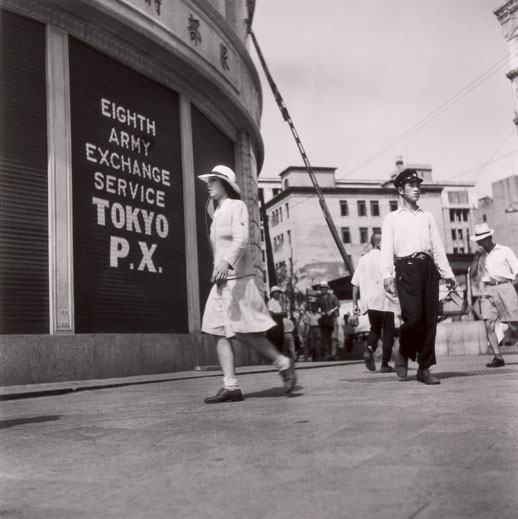

Some parallels did seem apparent with the other exhibitions however, the image of women being one of these. In the second section of the exhibition, entitled ‘Occupied Japan: Black Markets, Pxs and Women’, again the various facets of cultural change were pictured through the many roles women were depicted in. The third section ‘Liberation – Eros and Realism’, featured the prominence of the nude in 1950s photography, where female representation was a vehicle for symbolic visual modernity; in this case the sexual/spiritual ‘liberation’ of the 1950s, following the literal liberation from the American supreme command ‘administrators’ in late 1948.

In light of the number of post-occupation images, the exhibition title’s emphasis of “occupied Japan”, while arresting, seemed too narrow. Even if presenting the trope through which the period was being interpreted curatorially, the images suggested something more complex than simply ‘losers’, or ‘victims’, which could have been better reflected in a more nuanced title. This is the case with the following two instalments as well.

The ‘poles’ of tradition and modernity – East versus West – also seem to remain intact however, when we read later in the exhibition that the post-war period was “the first full-scale cultural interface between East and West since the dawn of Japanese history.” Indeed it may have been, but like the Showa Boogie-Woogie exhibition, the issue of the quick assimilation and appropriation of ‘foreign’ forms by Japan throughout the twentieth century was yet to be adequately addressed.

One of the sources of appeal in these exhibitions was to gain a better understanding of the contemporary cultural positioning of visual arts from the recent past. Returning to ‘Taisho Chic’, the exhibition was initially shown at the Honolulu Academy of Arts in mid 2002, and has travelled widely in the US, and overseas, before arriving in Japan, from where it will continue to be shown in other countries. It is largely based on a collection acquired from American, Patricia Salmon, who had collected the works while living in Japan in the 1960s and 70s.

Salmon has said she collected believing the works to be the beginning of modern Japanese art, and yet found that Japanese and foreign dealers were largely disinterested. Like netsuke and ukiyo-e previously; through a process of re-introduction and reinterpretation, this work is now being appreciated anew in Japan.

Thus, this significant comment on early Japanese visual modernity remains just one stop on the four-part itinerary. So why now, in Tokyo, some five years later? Similarly new approaches to this period, notably the exhibition ‘Modern Boy, Modern Girl’, have also been collaborative projects between Japanese and non-Japanese, academics and curators, in this case also, being initially ‘premiered’ outside of Japan.

There also remains the loaded question of how contemporary Japanese viewers ‘see’ such work? This is particularly interesting considering how many major issues for Japan today are still directly linked to the ‘position’ of popular opinion vis a vis the country’s experiences in the early to mid twentieth century. The ‘Taisho Chic’ pamphlet writes about the exhibiting of these works after a 30 year absence from Japanese shores as a kind of ‘home coming’; literally using a Japanese phrasing that would usually describe a married women returning to her parents home. Once again the complex journey of these images, not only in their initial production, but in the equally turbulent decades that followed, did not seem adequately engaged with. How did this work originally leave Japan, and why should it be brought back, as an ‘import’ exhibition, into this former imperial residence, at this point in time? As for the handful of kimono-clad young ladies in the Teien Museum the day I attended; enjoying a not uncommon bit of ‘traditional’ style on a weekend outing, I wondered what they made of the gender representation and neo-traditional conservative modernism I was seeing in Three Sisters, for example? But before I could enquire they had oohed and aahed, and tottered away to the upstairs sunroom.

While the two latter exhibitions dealt with photographic, and generally ‘documentary’ material, this should not overshadow the possibilities for direct comparison of curatorial approaches to historical representation with Taisho Chic. As suggested earlier, aside from the handful of prominent paintings an prints, much of this exhibition also featured craft objects, designer objects, commercial publications and advertising (such as the song-books). The ‘artworks’ themselves were also often directly linked to commercial realities in subject choice, commissions and so on. The contextual relevance of the work as historical documents was also amplified by the museum itself, in which the hanging nihonga images could not have seemed more at home, bringing the period to life.

Critical curatorial approaches to the many questions this essay has circled are slowly appearing, as each of these exhibitions evidences. Issues do remain, however, possibly beyond the scope of these recent exhibitions, implicating a broader want of critical engagement in the exhibition of recent Japanese visual arts to offer a visual structuring of the often turbulent times they have navigated—like all arts—on behalf of the nation, collectors, artists, audience and subject.

Art, of course, is just one manifestation of what is nowadays a much more abundant popular visual culture. For this reason, though anecdotal, it is possible to conclude by pointing to a fascinating, if somewhat bizarre, series of images advertising new plasma screen televisions. Sometimes also set in an artist’s atelier, or beside a famous masterpiece; a middle-aged Japanese women in kimono, who seems to be inhabiting an altogether other space and time, is pictured standing beside a plasma screen television. She does not look at it, or otherwise engage with it. She, as traditional refinement herself, is merely ‘present’. It would seem that advertising companies, no less than creators and consumers of visual arts previously, are well aware of the importance of this visualising, and reinforcing, of tradition and modernity. Questioning such persistent visual-historical tropes should be a task that art exhibitions, and the institutions behind, can not only exhibit but confront.

—

1 This is in fact the title of one of the two essays in the English catalogue. See Minicchiello, Sharon A. ‘Greater Taisho: Japan 1900-1930’, Taisho Chic: Japanese Modernity, Nostalgia, and Deco, Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2001.

2 Ibid, p.47.

3 Held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; November 7 – December 24, 2006.

4 Note that the museum’s name; kawasaki shimin mujiumu, would literally translate as, ‘Kawasaki Citizen’s Museum’.

5 A recent advertisement even invites people, by way of old trams, to go “into a nostalgic future”, or “into the good old future”. (natsukashii mirai he) See image.

6 Note the recent comprehensive treatment of Otsuji’s oeuvre, including the work ‘Objet’, in the retrospective exhibition ‘Otsuji Kiyoshi: Photographs as collaborations’; Shoto Museum (Shibuya), 5 June – 16 July; 2007.

Olivier Krischer

Olivier Krischer