Empty Looking: Spontaneous Reflecting on One’s Thoughts

Noriyuki Haraguchi is known for his large sculptural works that tackle the complex issues of industrialism and militarism in his 40+ year career. Despite this his refined approach is far broader than these symbolic works. In fact he has continuously expressed more contemplative thoughts on paper, and he is currently displaying these subtle works in an exhibition at Miyake Fine Arts.

I travelled to Miura peninsula for this interview with Haraguchi and ended up with an unforgettable experience. After departing from the crowds in Enoshima we ended up in the quiet but refined town of Zushi. After hours of animated conversation in a local izakaya, the trip ended the next morning with an excursion to Haraguchi’s hometown. As I inhaled the ocean’s stale air and absorbed the paradoxes of Yokosuka I glimpsed at the source for Haraguchi’s unforgiving intensity.

I’m not a big fan of traditional things. Naturally, I go to Kyoto and Nara but I don’t exactly love those places. For example I really hate going to hot springs, watching maple leaves in the autumn, observing cherry blossoms and those kinds of things.

I don’t like what people ordinarily think of as beautiful. Actually I think what is considered nothing has beauty. It’s not about conscious viewing, but rather blank viewing, I like empty looking.

Going out with a camera, to catch a picture of the setting sunlight…it’s not about that. There are old guys who get up in the morning and set their tripods. They aim for the shutter chance, but I think that type of activity is nonsense. They don’t understand beauty. Beauty is simply doing nothing but looking.

It could be too beautiful…in the most ordinary sense of the word “beauty.”

I theoretically dislike that way of thinking about beauty. For example, a teacup that is considered to be a masterpiece, or a National Treasure, I really hate those. Everyone says, “This is amazing because it’s a National Treasure!” “Oh, this is beautiful isn’t it…” – unfortunately seeing it that way. I don’t like the self that sees it that way. That’s why nothing at all is the most beautiful thing.

The things nobody focuses on I call, “Something that is nothing.” Things like a rusting iron pole falling down at a construction site. I like finding things like that.

I used a lot of industrial goods, but never really used natural wood, natural stone and those sorts of things, but rather I use industrial materials like iron and oil.

What is it you are able to express with artificial materials?

Hmm, that’s difficult to say.

It’s quite different from Minimal Art, isn’t it?

Of course to some degree it’s not just something visual, it includes performance, and it is composed of bodily actions. By means of these bodily actions its not just about placing work, starting something up, that sort of action, one part of the body, such as society, industrial materials and manufacturing.

Changing the topic, what about your upcoming exhibition plans?

Miyake Fine Art in Kiyosumi will have my solo show from May 8.

Which works will you present?

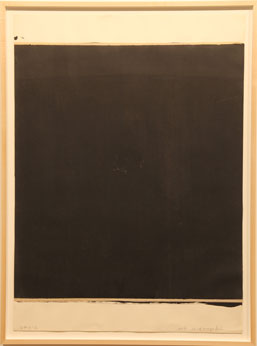

They are all flat works on paper. They are similar to the lead works I presented at BankART last year.

From what sensibility did you produce those works on paper?

It’s a very abstract answer, but I have the feeling like I’m implementing spontaneous thoughts.

Is the way you express yourself on paper more personal than the way you do with iron?

In the case of objects such as 3D things, preparation is very important. It takes three months, half a year, even a whole year. Because of that, completing them uses up lots of energy. On the other hand, 2D works take less energy and are done quickly.

Simplicity?

Yes, simplicity. For example a single pencil line, drawn hard, matches the pattern of one’s thoughts. The viewer may say, “What is this? Is this just a single pencil line, drawn just like this?” But inside oneself it is an extremely complex world, entering that place of complete abstraction. It is very efficient, rational, and yet impromptu. In three parts, or five parts it becomes complete. As many months pass suddenly, “I’ve done this amazing work!”

I was an oil painting major in university, a western painting major. Thus I began from painting and then in the second year of study I gradually became 3D, then installation. Then design, also drawing and works on paper, collage. I could say I really enjoyed them, I mean I was good at those things.

So from the start until now you have continued with them?

I didn’t come from a sculptural background. I never sculpted a stone, never carved wood never made clay statues, and never made any engravings. Therefore I have a painterly approach.

Combining the geometry of the canvas with the lead?

That kind of space, painterly space such as real things in three-dimensional space, it’s just not there. They are intuitive images.

I became very intrigued by those works in your exhibition at BankArt last year. I looked at the combinations of canvas and lead and just stared blankly. I had the feeling of forgetting about time.

I’m glad to hear that.

Of course your flat works are not so often put into print and are less well known than your sculptural ones.

Yeah that’s true. Other works are more famous, but in reality I’m just making those works on paper at home all the time. Those are really my creative thoughts, the most fundamental parts. I guess those kind of actions are just a sort of training.

Translated by James Jack. Transcription assistance kindly provided by Saka Matsushita.

The Noriyuki Haraguchi exhibition is showing at Miyake Fine Art until June 12.

James Jack

James Jack