Drawings from a Half-Conscious Space

Flickering images on a screen and an energetic cacophony of transformations occurs. A figure riding a motorcycle turns into a swirling mass of marks that swirl and reform into a face. The face then disintegrates, only to rise, fall and become a small child getting on and off a chair. This is not a blockbuster anime but the work of artist Chikara Matsumoto.

In a country where, at least traditionally humility beats hype, Chikara is the epithet of tradition. Dressed in smart casual neutral colors, speaking gently but with a great intelligence and creative sensibility he seems both veteran and visionary. His work has been exhibited in Japan and abroad but he remains, like so many contemporary Japanese artists, prolific yet unwilling to jump into the spotlight. As Asia becomes an increasingly sought-after cultural hotspot, many Japanese artists remain quietly productive, independent of a very selective art market. Matsumoto, born in 1967, has been modestly working away on group shows and sometimes commercially for TV. Rather than produce work that wows viewers with superior technology or clever special effects, he emphasizes the hand-made. But don’t let that fool you: underneath his work lies a warm, intriguing vision that questions not only the current place of art production but also the process of artistic creation itself.

I first encountered his work in December 2005 at Tokyo Wonder Site Shibuya in the show “Fuckin’ Brilliant!” a collaboration between artists from the UK and Japan. The works he was showing there — Heavy Metal, a large drawing scroll hooked up to a video camera and other animations, displayed inside Chikara Pod a “space life boat” of sorts — were an appraisal of pure imagination and its power to imbue the simplest of materials with a new narrative. Either he was deliberately using a simplistic style like the Parisian Art Brut artists such as Claude Dubuffet or he had a different agenda. However, his work does not seem to fit neatly into any ‘faux naïve’ style. It’s not twee, ironic or trying to strip a genre, person, or idea of its aura. Perhaps now, in our media-savvy and psychologically aware society, the idea that mark-making could somehow correlate with the subconscious layer of our selves seems nostalgic, or could even be interpreted as deliberately playing dumb. In Japan the term Heta Uma has been used to describe a simplistic stylized art-making technique but there is some debate about whether the artists are simplifying their work or merely being true to their own style. Unlike British artists of the 1990s whose work flaunted an ironic approach, many young artists in Japan are responding to their experiences in a direct rather than ironic way. Here, Hello Kitty is cute, not cynical. Matsumoto’s work seems neither.

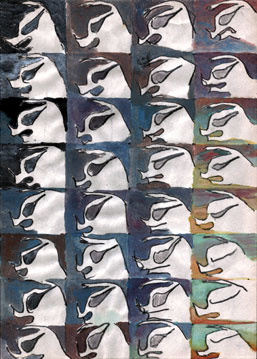

Modernism championed the individual and his or her unique vision; Postmodernism demystified dominant institutional narratives and sought to make response a matter of subjective interpretation. But we are now living in a paradigm of mass communication and user-interface mentality. Institutions as entities themselves are questioning the nature of their position in an information rich environment. The effect of technology on our perceptions of art and more broadly our perceptions of what we are culturally is very much still in flux today. Matsumoto uses drawings alongside digitized animations often in a collaborative context; his work bridges the gap between the handmade and more advanced technology. The animations are created using hand drawn pictures on sheets of B5 paper rather than on a laptop with a variety of digital manipulation. The drawings or ‘cels’ are created usually with pencil, crayons, and ink — materials you could find in any trusty one hundred yen shop. He doesn’t edit.

Comparing his work to animation, and specifically the legacy of Japanese anime is useful, for it makes it clear what Matsumoto’s work is not. Anime has a style that is so specific that comic and animation artists need to study the visual language as though it were an actual language. Unlike animation, he is producing independent work by hand — work that is much rougher in look than a tight black and white anime. Although ultimately he digitizes the drawings they retain a sense of the human touch and process. Backlit on a light-box, the paper glows like the skin of a Chinese lantern giving visual warmth to the atmospheric quality of the final animations. During our interview he spoke about the lanterns as an inspiration. “The Magic Lantern”, as it was nicknamed, was an early slide projector. The images were painted on glass and projected onto fabric, in the late 19th century it was one of the only projection materials available. The use of light adds certain warmth, a quality that Matsumoto likes. Similarly during the summer Obon holiday, paper lamps float down rivers representing the departed souls. His work captures this sense of the liminal, the journey, and the transformative.

Blakian oranges, yellows and purples depict the night sky or twilight, times between light and darkness where in Japanese tradition spirits are able to play or wreak damage. The halfway point between night and morning holds a special power because of it ambiguousness: it is the time when yokai (apparitions, demons) exist, and yet you cannot see them. In the same way, his drawings fill in the spaces between the end and the beginning — a half-conscious space. When talking about the source of the images, he refers to “the other inside yourself”, and he draws me a picture to illustrate how the artwork is more than just an object but a point between two people who are both connected to each other through the process of creation and reception. Perhaps most similar to Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious, Matsumoto believes that the end of the creation and the beginning feed into each other; he sees himself as a conduit for atmosphere, feeling things that surface. Discussing the role of the artist, he explained that where scientists seek to prove their theories through experimentation, artists and poets may have a truth to prove — the nature of beauty — but they achieve it through the formulation of images and words. For him, the artist’s role is one of “cutting through society” to create something, but “not watered down, something potent and deep”. Like the work of the respected Studio Ghibli, Matsumoto’s work is infused with a kind of animism and transformative power, but his creative process links his work much more with groups like Fluxus and music.

Artists are often disseminators of their own brand hype which is often sold on the basis of its concept. In contrast, musicians often play freely with improvisation without having to justify their music intellectually. Matsumoto deliberately loops his images so that there is no beginning and ending but a sense of change and gathering. His films have motifs that reoccur and even though unedited retain a certain rhythm. Meeting at a casual creative gathering in Shibuya in May 2000 the Japanese electronic band “organ-o-rounge” approached him after watching him make a live soundtrack to his own animation. What is unusual about their collaboration is that none of them see or hear the others work until the event at which the sound and image are to be combined. In this way they work in parallel, but not strictly speaking in collaboration as we usually understand it. It is a process of exploration: through their creation they generate a new form that is neither sound nor image but a combination of both. Both use loops, and fragments become broken, transform and rejoin or reconfigure. He draws music and they draw with their music, a process that he describes as “expressing his sounds onto paper, sending them an invisible letter”.

Currently exhibiting in both traditional galleries and an assortment of ‘live’ venues with ‘organ-o-rounge’, Chikara Matsumoto is a unique artist whose drawing transgresses the boundaries of form, both still and moving and yet neither definitively one nor the other. The tension between what is High Art and what many people called Art Brut is perhaps outmoded in the 21st century environment of cross pollination between the arts, music, design, film, animation and graphics. However the genesis of creativity and the debate about the nature and place of art remains relevant. Like Picasso, he sidesteps questions of appropriateness of form to pursue his inner vision and prolific output. As we move into the eighth year of the twenty first century, perhaps the role, materials and idea of art itself are in a process of transformation. For Chikara Matsumoto his individual creative process links him to a deeper sense of invisible connections between sound, image color and also time itself as images loop and feedback into a continual renewal or flow much like thought itself.

—

Thanks to Lena Oishi for interpreting during the interview.

Rachel Carvosso

Rachel Carvosso