Drawing Conclusions

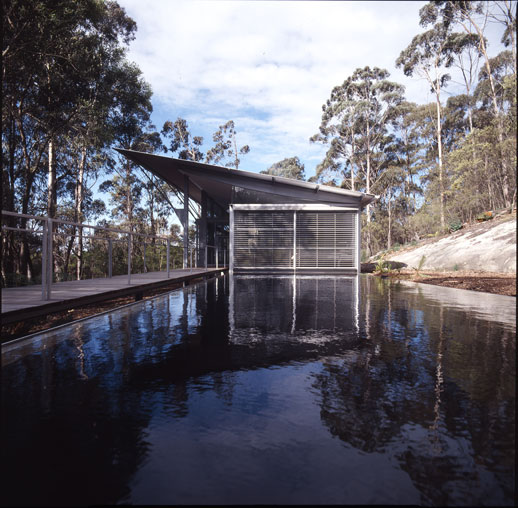

“This is architecture…about the human spirit…serene.” This is how Glenn Murcutt explains his work in Gallery Ma’s architectural exhibition “Thinking Drawing, Working Drawing,” a collection of Murcutt’s single-family homes and an art center, all located in Australia. Murcutt eschews glitzy forms and fashionable theories, pursuing instead the visceral effects of nature and coordinating them into subtle poetic works of integrally environmental architecture. The wonderfully conceived exhibition presents Murcutt, the man and the work, in a systematic manner.

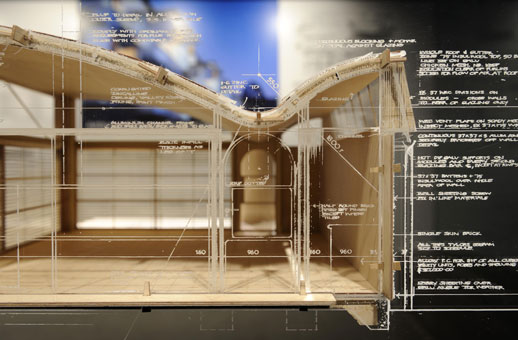

The lower gallery surveys five projects — four houses and the Boyd Art Center (1996–99). Each house, including the Marie Short House (1974–75) that Murcutt purchased and renovated in 1980, is shown with succinct text, photos, sketches, drawings and an ingenious presentation of a sectional model cantilevered from suspended clear acrylic on which the section drawing has been etched — a unique combination of drawing and model that helps non-architects to ‘read’ the drawings. This room allows easy comparison of the projects and the development of common typologies and strategies—the use of the split plan (bathrooms, kitchens and storage on one side of a corridor and the living, dining and sleeping spaces on the other), opaque walls versus large windows, and the use of commonplace materials such as wood, brick, and corrugated steel.

The upper gallery exhibits only drawings, reinforcing Murcutt’s declaration that recently he has quit building models and now only develops projects by drawing. This move comes after years of experience and learning to understand the space of drawing and its built consequence. Consequently walls are lined with sketches and working drawings — a rarity in most architecture exhibitions—of the Walsh House, Marie Short / Murcutt House, and the Murcutt-Lewin House. There are also tables with sketchbooks and sets of working drawings of the Boyd Art Center and the Magney, Marika-Alderton, and Simpson-Lee Houses, as well as the two accompanying monographs — one of drawings and one of photos, to leisurely review.

Additionally two revealing documentary videos, one in each gallery space, show biographical material, examine buildings and interview people from Murcutt’s long and somewhat quiet career. In one, Murcutt, awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 2002, defends his most common accusation of not designing large buildings by challenging his critics to “do a decent little building.” The exhibition indeed shows many decent little buildings. His projects are reminders of how easily building orientation, passive solar for heating and lighting, operable windows and walls for ventilation, and water collecting cisterns can provide simple environmentally friendly living conditions.

However, with Murcutt’s growing list of public projects — visitor centers, museums, galleries, hotels, restaurants and wineries — it is dismaying to see so many old, albeit iconic, residential projects. Of the seven projects, only the Walsh House (2001–05) and the Murcutt-Lewin House and Studio (2000–03) are of this century and two are Murcutt’s own homes. There is disappointingly no reference to more recent work or works-in-progress.

Murcutt, a solo practitioner for his entire career, proclaims architecture as a process of discovery that allows people to perceive what is around them. The bilingual (Japanese-English) “Thinking Drawing, Working Drawing” allows visitors to easily compare projects through a systematic presentation of common format of text, sketch, drawing. Visitors discover the nuances that make each building uniquely responsive to its site, program and client—revealing Murcutt’s buildings as finely tuned machines in their own wildernesses.

James Way

James Way